Is Your Radio Station Serving Expired Hits?

Billboard Magazine thinks so.

When we last visited, we explored why Billboard is suddenly kicking some of the biggest hits off of its Hot 100 Songs Chart: Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” Benson Boone’s “Beautiful Things,” and “Die With a Smile” from Lady Gaga & Bruno Mars have all vanished from the Hot 100 after well over a year on the chart under the new policy.

Turn on your local FM Pop station today. You won’t wait long to hear all of these songs.

That previous post (Billboard Has Had Enough of Your Teddy Swims) showed why it’s radio—not streaming—that ultimately pushed Billboard to dramatically change the rules for removing older this from the Hot 100.

Let’s dive into one of those songs that Billboard has kicked out of the Hot 100, to see how radio’s primary gauge of new music popularity compares to the song’s popularity on streaming.

How radio picks its hits

The primary tool that big radio stations use to pick current songs is callout research, a name that hearkens to randomly calling home phone numbers looking for listeners willing to rate songs over the phone.

It’s now done online using paid research panelists, but the premise remains the same:

Find people who listen to your radio station and reflect your core listeners in age, gender, and ethnicity.

Play them seven-second snippets of about 30 currently popular songs.

Ask them if they recognize the song and—if they do—if they like or dislike the song.

Recurrents—the leftovers you still love

Back in the day, radio stations primarily used sales data to decide which songs to play. When sales dried up, that song vanished from your radio. After a couple of years, stations might occasionally play it again as what the kids now call a throwback. Songs that were half a year old were non-existent on Top 40.

Then, hippies inadvertently spawned corporate callout research—and it inadvertently revealed that people still love songs long after new fans have stopped buying them.

This new finding gave rise to a kind of song that radio programmers call a “recurrent:” It’s a designation for a song that’s become a bit too old for listeners to consider it a “current” hit, but it’s not old enough to be a blast from the past. Usually, a few months to a couple of years old, these “recurrents” are too old to be new, but too new to be old.

They’re also the most highly familiar and often still be most beloved songs in callout.

What songs top callout research?

Since callout research is typically customized for each radio station—and is expensive—it’s almost impossible to find callout data if you don’t work for the station that paid for it.

However, Coleman Insights offers a subscription-based nationwide callout called Integr8 USA Since September 2024, they’ve published their top 3 best-testing songs in RAMP (Radio and Music Pros) for their Top 40 and Hot AC reports.

Before we go further, two bias disclosures:

I spent 15 years leading Coleman Insights’ Integr8 New Music Research division, helping stations design their research and interpret the results. I haven’t been on their team for a while and therefore don’t speak for them, but I do remain a steadfast believer in their work.

I currently make my living analyzing music streaming data for radio, so I’m also a huge believer in the value of streaming users’ behavior to identify mass appeal hits.

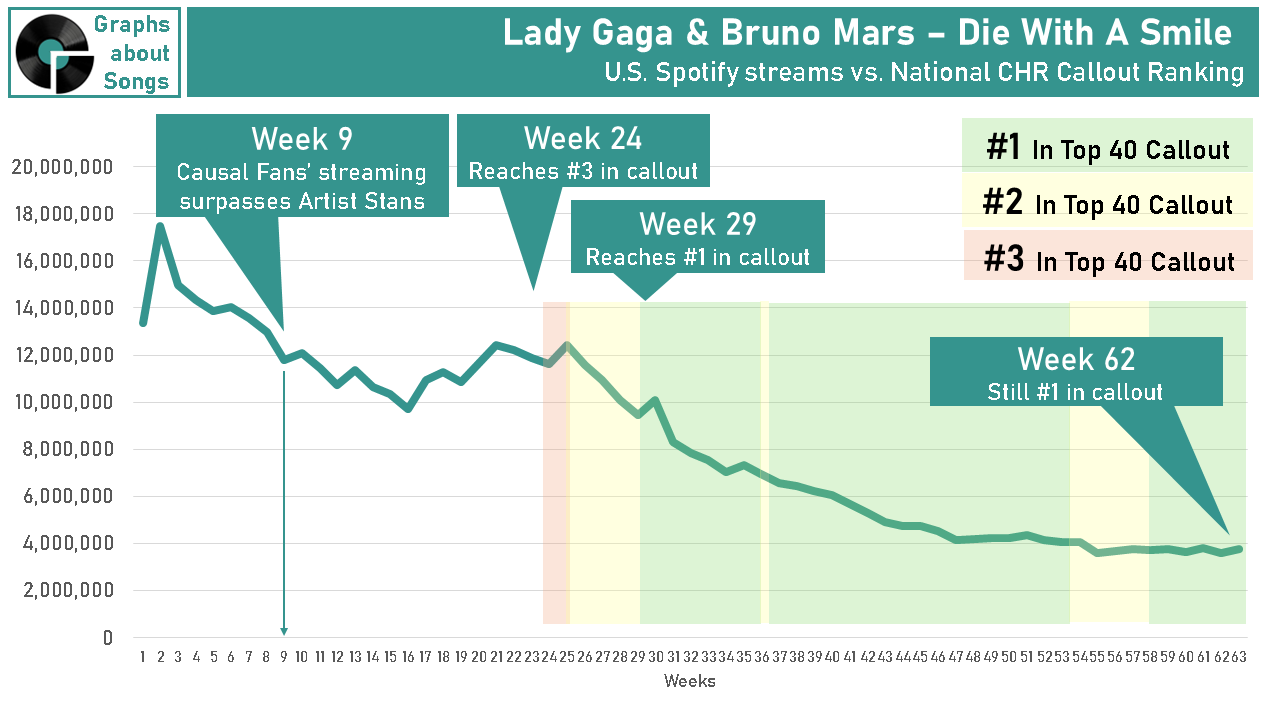

Let’s examine how Lady Gaga & Bruno Mars’ “Die With a Smile,” one of the songs Billboard targeted for removal from the Hot 100 due to age, performed in Integr8 USA’s Top 40 callout, compared to how fans consumed the song on Spotify.

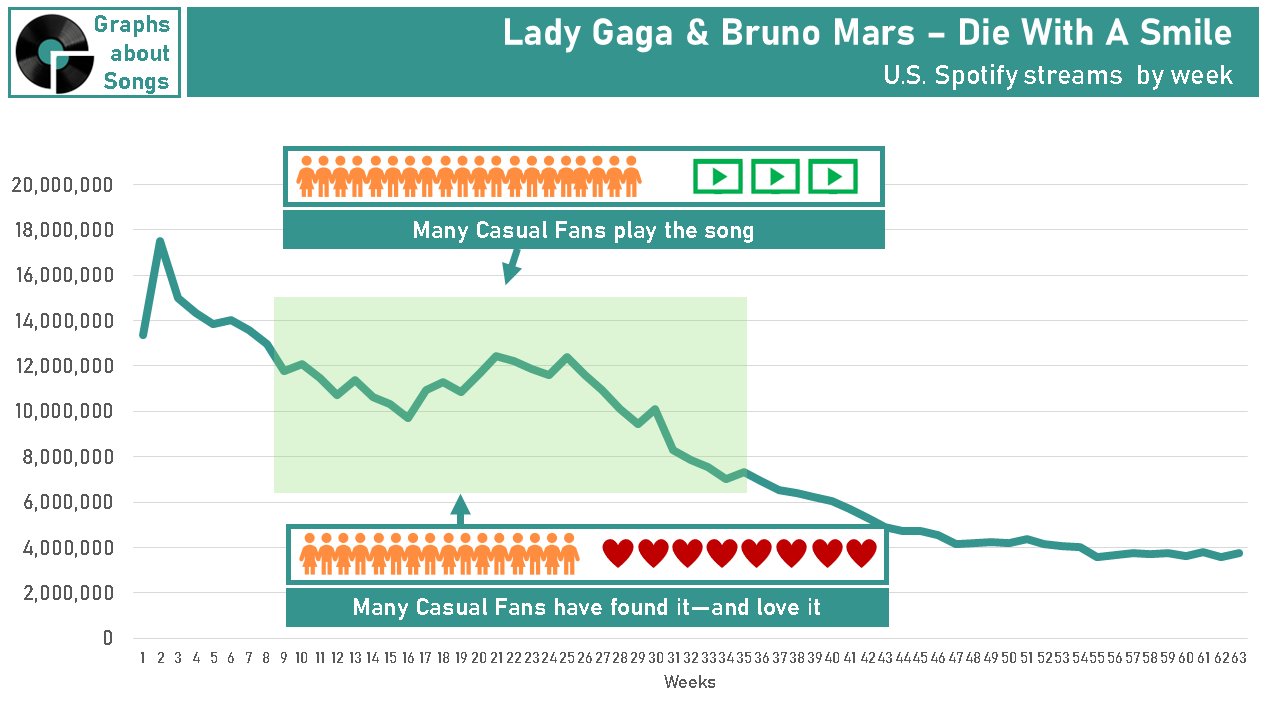

Before we dive in, understand that raw streaming data and callout research will inherently look different, particularly in the early weeks of a song’s life:

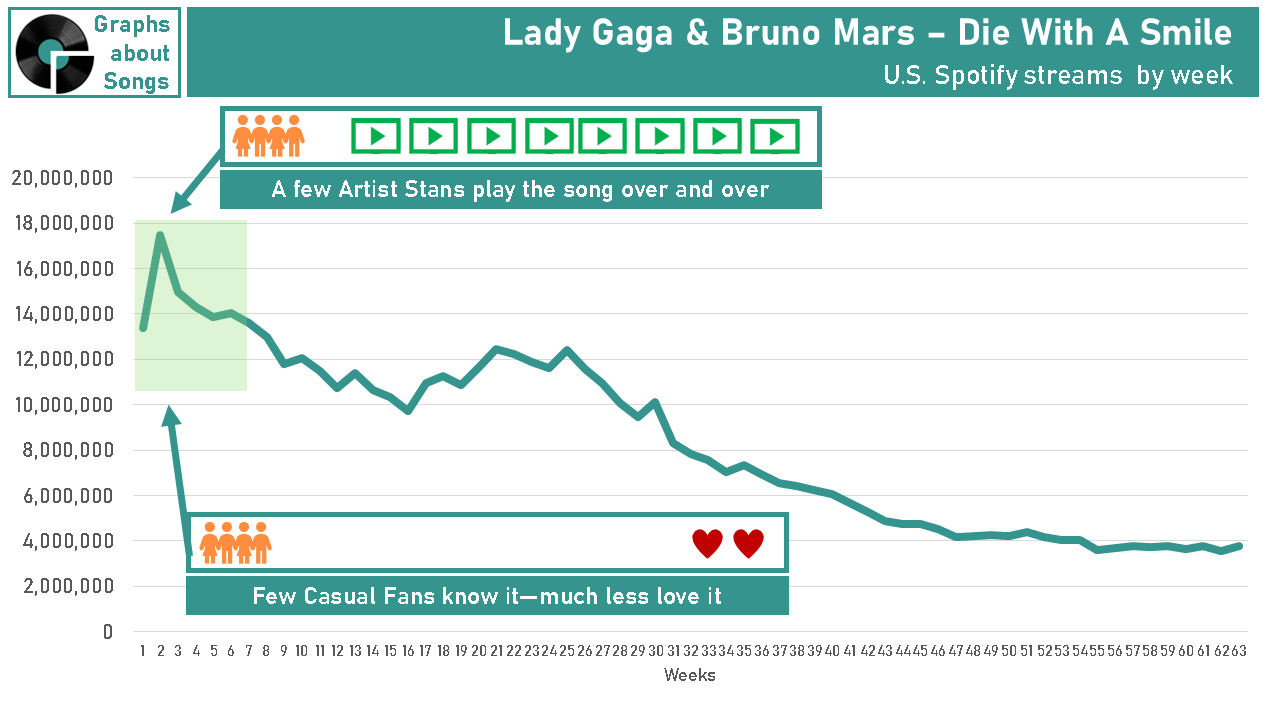

When a popular artist releases a new song, fans of that artist flock to Spotify et al. to check out their latest song and those mega-fans typically play that new song a lot. Since streaming data shows how many times a song is played—not how many people are playing it---those “Artist Stans” as I call it boost streaming numbers dramatically with their binge listening.

In comparison, callout research gauges how many people in the target audience know and love a song. Those Artist Stans who are racking up those streaming plays account for a minority of the fans who will ultimately like a hit song. For the vast majority of those “Casual Fans” as I call them, it typically takes eight weeks for most folks to become familiar with a song and ultimately grow to love it.

After those eight weeks give or take, we’d expect callout and streaming data to be in closer accord as Artist Stans stop playing a song repeatedly and Casual Fans have grown to know it, love it, and play it.

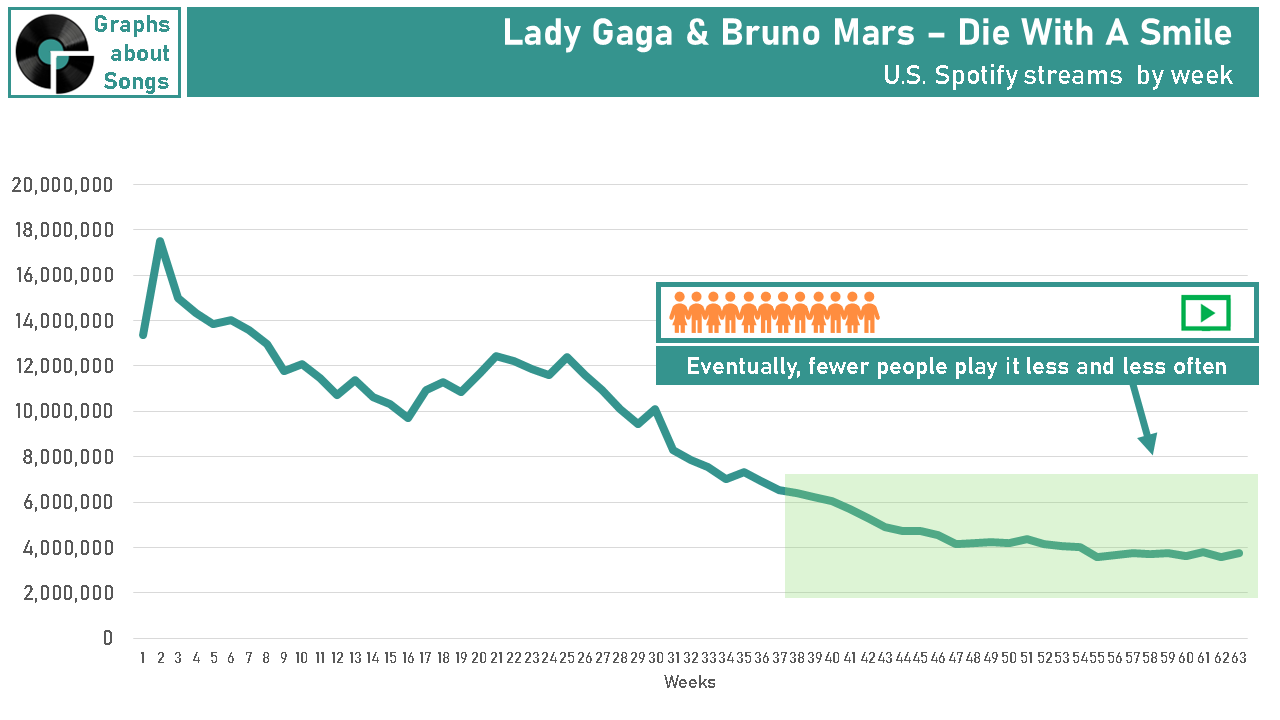

Finally, every song reaches a point where fewer fans play it—and those who still play it play it less and less often—than they did when the song was a current hit. That’s true even if they still say they love the song.

Bottom line: Don’t expect radio research to exactly mirror streaming behavior, especially in the first few weeks of a song’s life. After all, they’re not actually measuring the same thing: One is census-level behavioral data showing how many times a song gets played. The other is survey data showing opinions based on recognizing song snippets.

So how does “Die With A Smile” look in callout research?

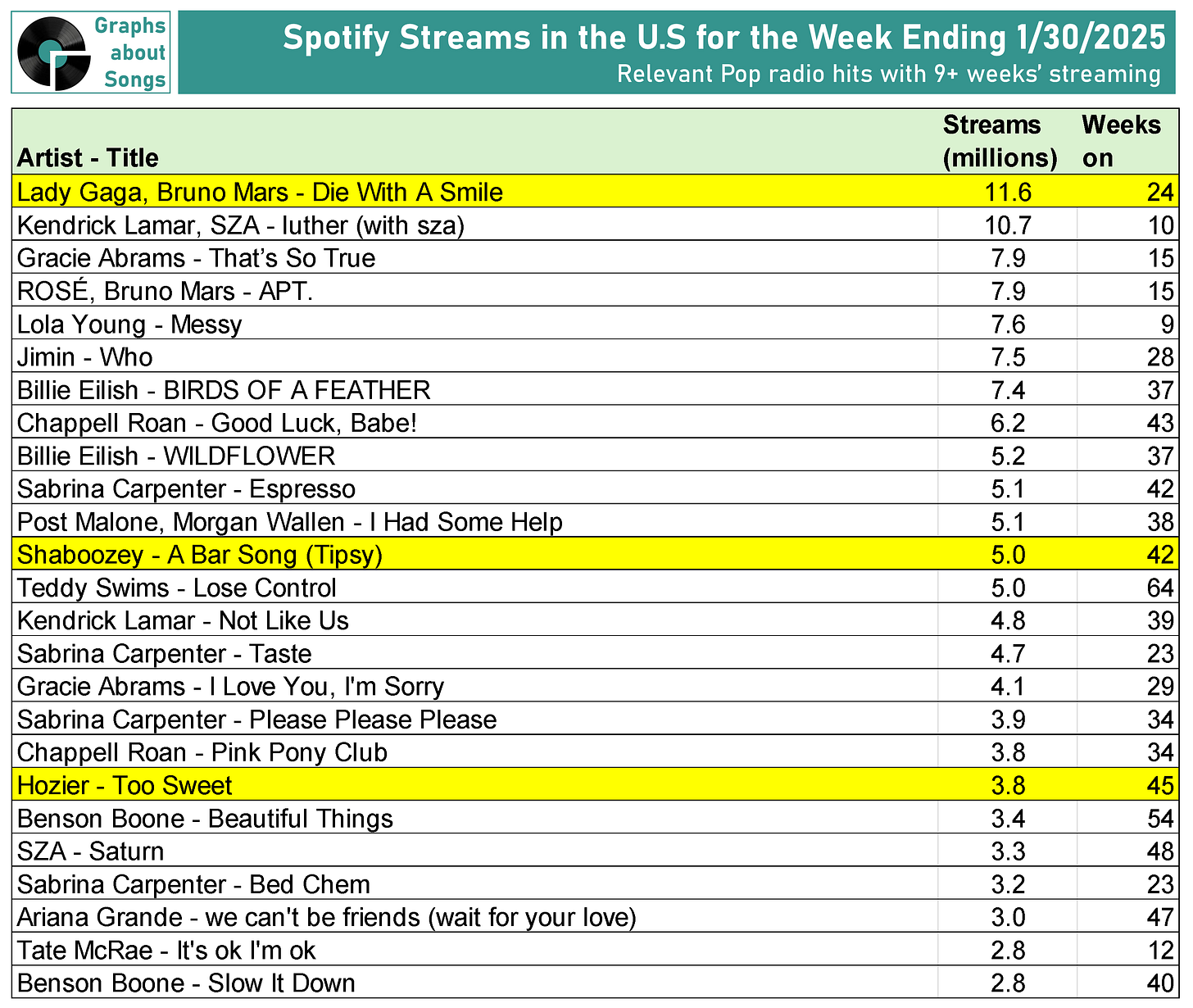

After being among the most-played songs on Spotify for 24 weeks, “Die With A Smile” reached the Top 3 songs in Integr8 USA’s Top 40 Callout for their report dated February 3rd, 2025. (Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” and Hozier’s “Too Sweet”, both almost a year old, were still #1 and #2 respectively.)

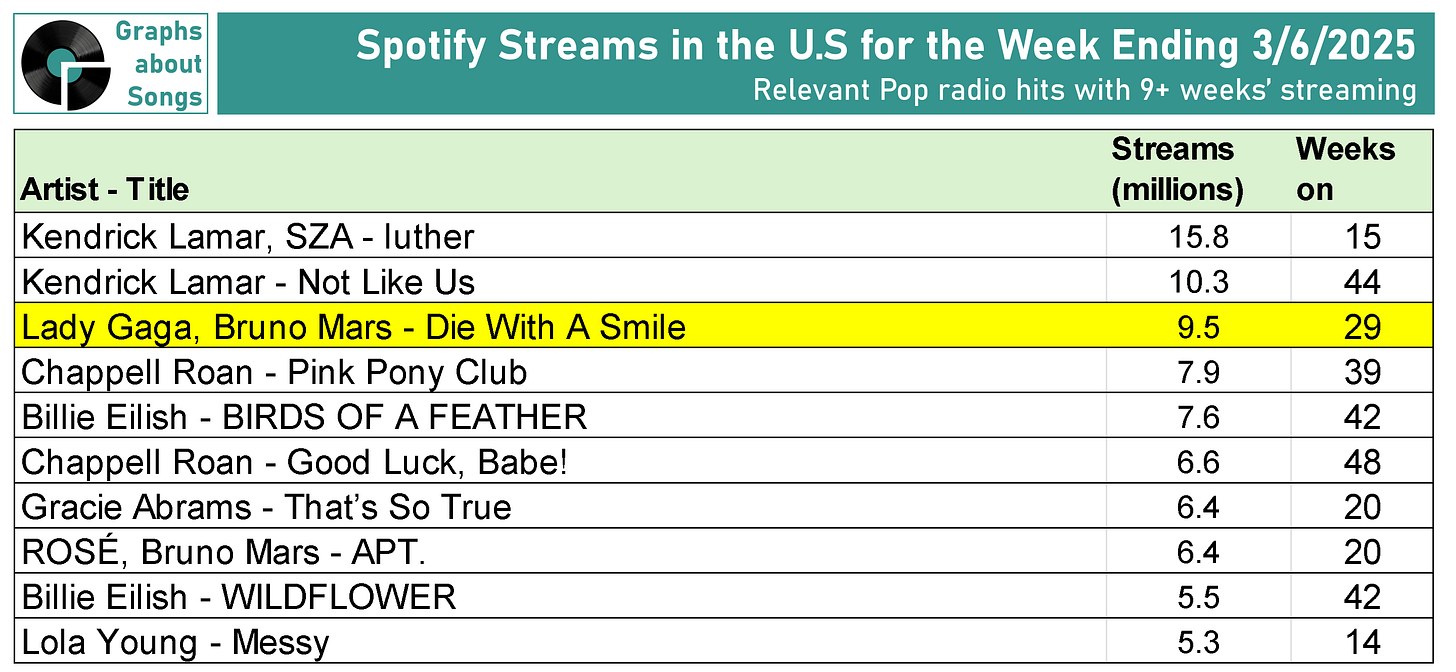

The chart below shows which established hits Spotify users in the U.S. played most that week. (“Established” here means those songs that have been around for more than eight weeks and, therefore, have become familiar among Casual Fans).

Five weeks later in its 29th week, “Die With A Smile” reached #1. At that point, Kendrick Lamar’s “luther” and “Not Like Us” were both bigger on Spotify, but “Die With a Smile” was still the most-played established pure Pop song on Spotify.

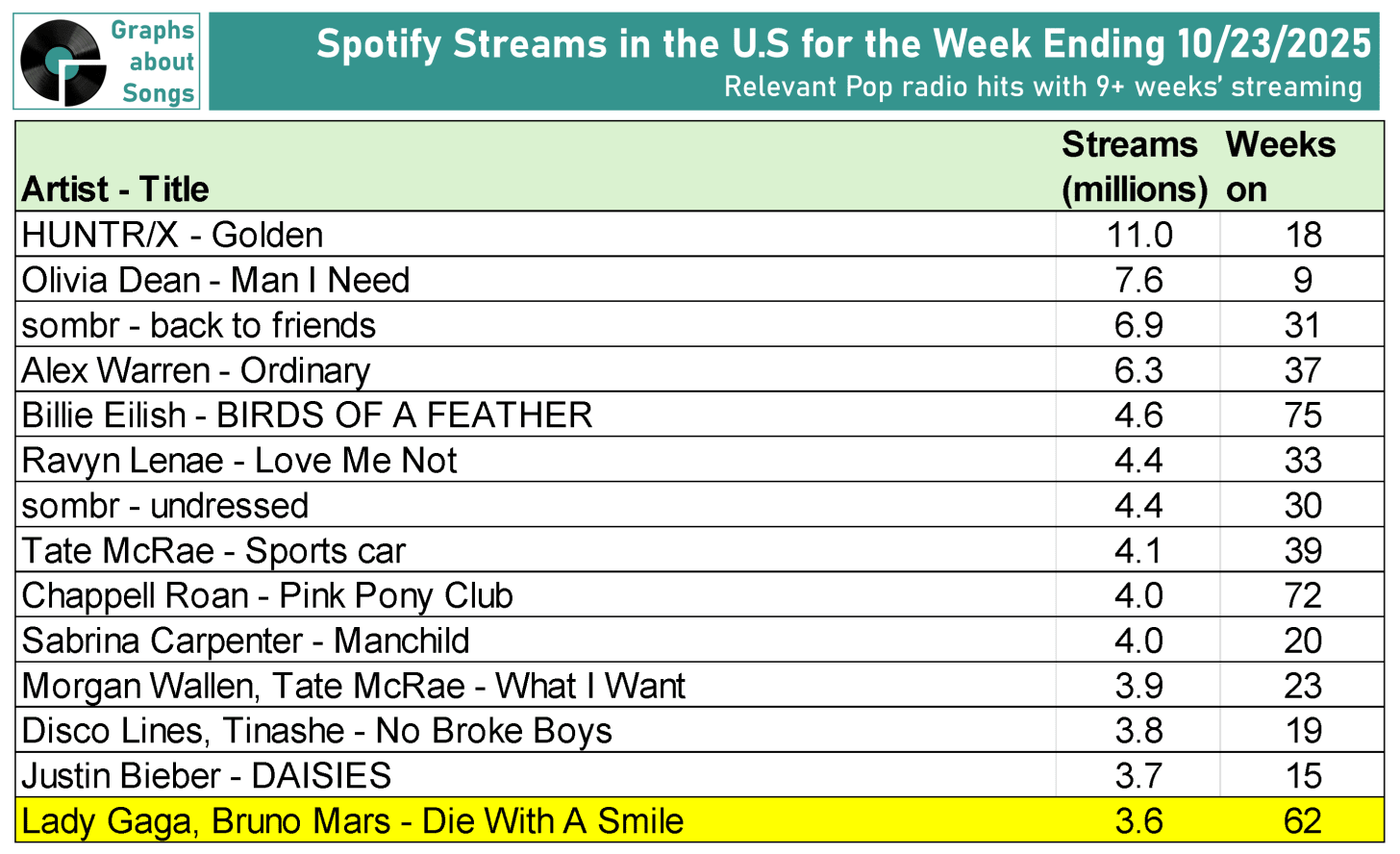

For the report ending October 27, 2025, “Die With a Smile” was still the #1 song respondents said they loved most in Integr8 USA’s Pop callout, 62 weeks after the song debuted.

What songs were listeners actually playing for themselves?

“Die With A Smile” got 3.8 million plays on Spotify in the U.S. that week. That’s only 30% as many weekly plays as it was when it first reached the Top 3 in Integr8 USA’s Top 40 callout.

While those nationwide research respondents said they still loved “Die With a Smile” more than any other song examined, America’s Spotify subscribers played 13 relevant, established Pop hits more often than they played “Die With A Smile.”

This same week, “Die With A Smile” remained the fourth most-played songs on U.S. radio. (Alex Warren’s “Ordinary” was the most-played song on Top 40 radio.)

The research that drives radio has kept “Die With A Smile” on the radio more often than fans are playing it for themselves. Therefore, it’s radio—not streaming—that spurred Billboard to create new rules to finally push “Die With A Smile” off the Hot 100 after 60 weeks on the chart.

Speaking of Ordinary, let’s examine Alex Warren’s 2025 hit—a likely song to vanish from the Hot 100 in the future thanks to Billboard’s new rules.

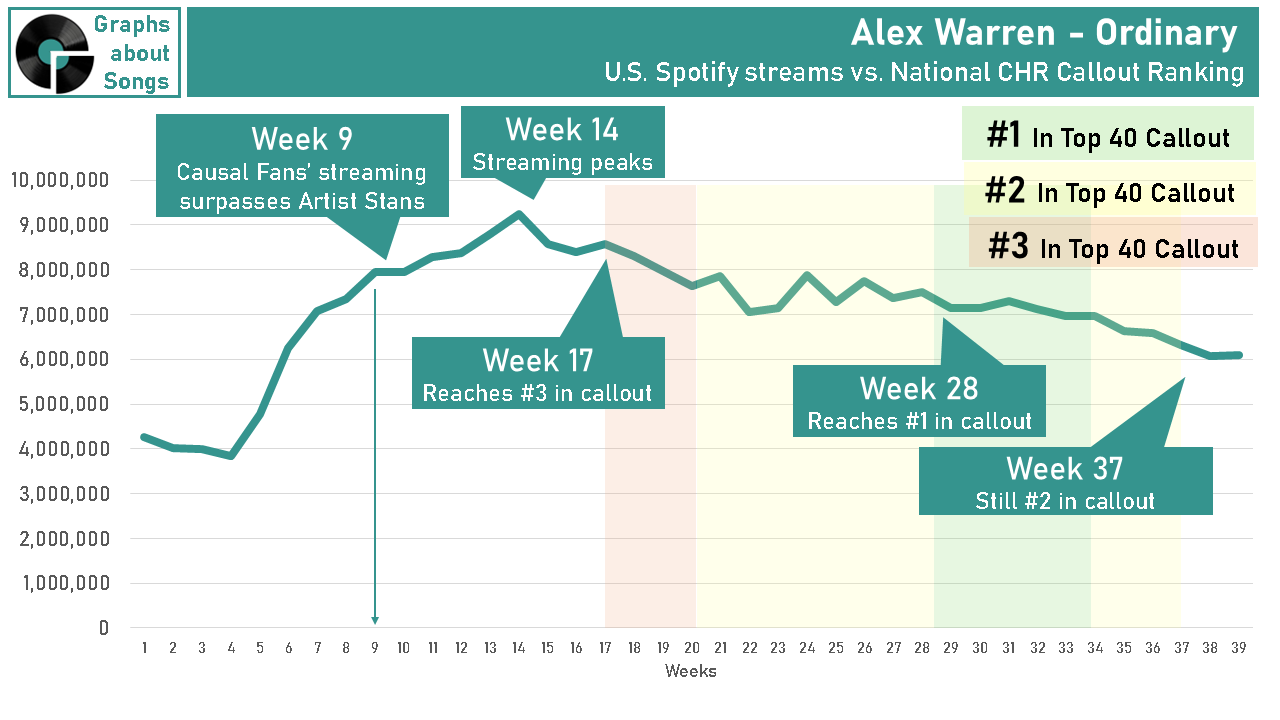

Unlike “Die With A Smile,” Alex Warren didn’t have a massive fan base anxiously awaiting “Ordinary’s” release. It grew its weekly Spotify plays slowly, as you’d typically expect popularity in radio’s callout research to grow. It took 14 weeks to reach it’s streaming peak.

It would take another three weeks before “Ordinary” reached the top 3 in Integr8 USA’s Top 40 research. “Ordinary” wouldn’t reach the top spot until 14 weeks after its streaming peak.

As of October 25th, 2025, “Ordinary,” now in its 37th week, is still #2 in Integr8 USA’s National Top 40 callout. It’s also still the 4th biggest established Pop song on Spotify. However, its weekly streams have fallen 32% from their peak week back in May.

Why do songs take so much longer to become popular in radio’s callout research than they do on streaming? Why are songs still among radio listeners’ favorites even when they’re months past their streaming peak? And is callout research slower than it used to be?

Callout Is Getting Slower… Much Slower

Historically, it took weeks for big songs to top callout reports, not months.

But even during just the past year, the top songs in callout are taking a lot longer to reach their peak are staying atop callout research longer.

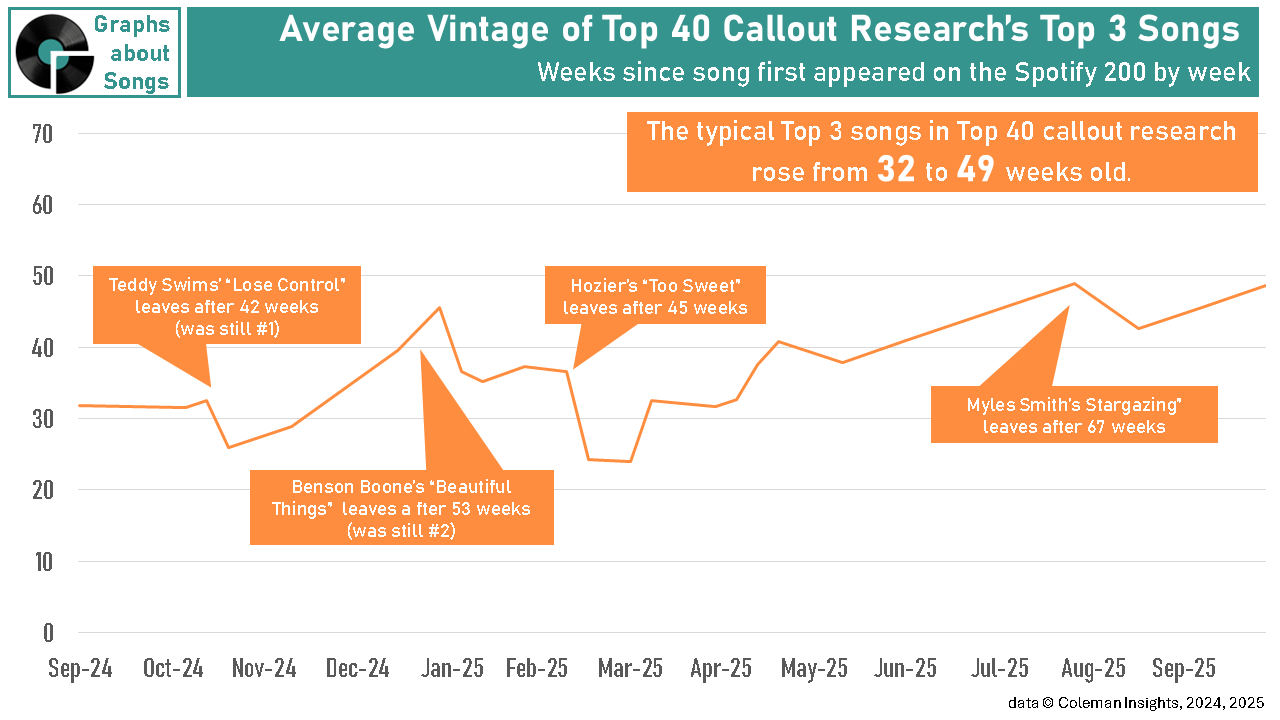

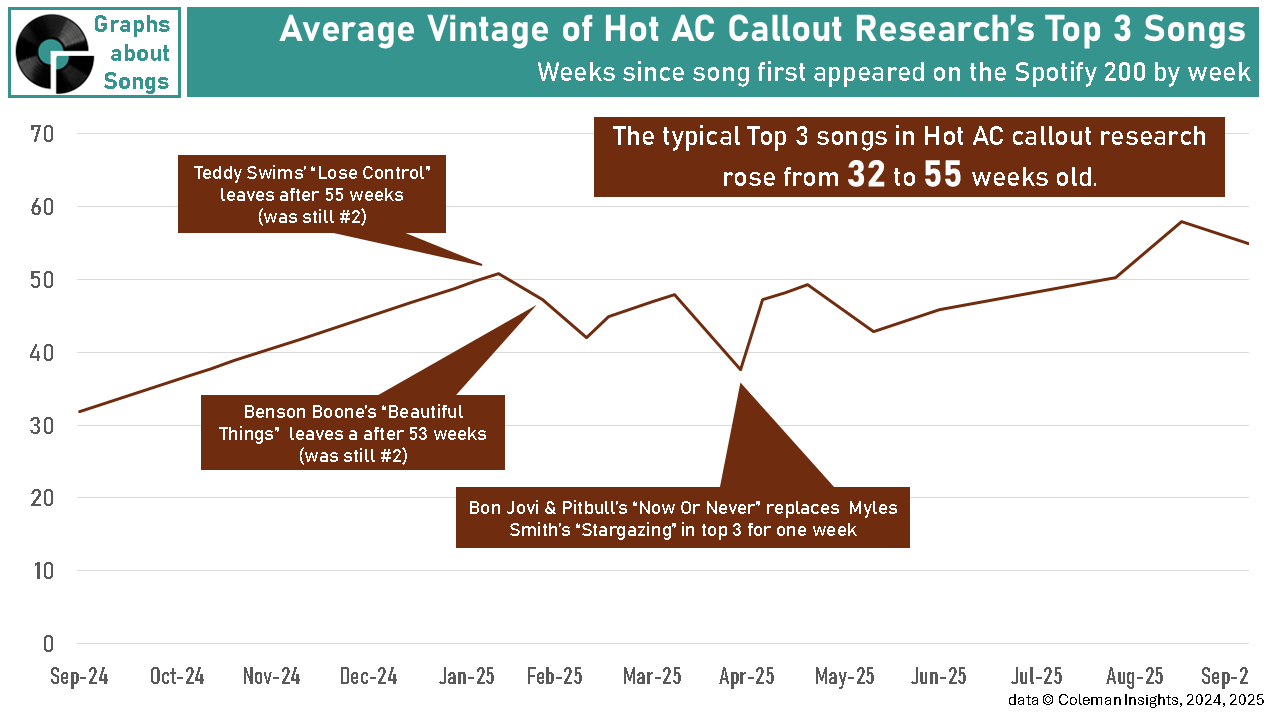

The graph below shows the average vintage of the Top 3 songs in Integr8 USA’s Top 40 and Hot Adult Contemporary research from September 2024 to October 2025. In the research for Top 40 stations, the average top 3 best-testing songs are now 17 weeks older than they were in September of last year.

In the Hot AC research, the top 3 songs are now on average 23 weeks older.

Its possible listeners favorite songs could be even older: Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” was still #1 in its final Integr8 USA’s Top 40 report when it was 55 weeks old. Benson Boone’s “Beautiful Things” another target of the Hot 100’s new policy, was still #2 when it was 57 weeks old. (While pure conjecture on my part, it’s standard practice to stop testing songs in new music research once they become too old—so Coleman Insights, being among radio’s most respected research firms, may have followed this practice.)

So why are songs testing best for radio getting so darn old?

Five Reasons Old Songs Dominate New Music Research

In some ways, the research reflects the state of current pop music. In others, radio’s callout research is making those problems artificially worse.

1) The average age of radio listeners is getting older.

Folks in their teens, twenties, and even their early thirties, are spending less and less time with FM radio. That leaves older listeners in the 35- to 54 age range making up a larger percentage of who still tunes in. Many programmers logically survey the 36-year-old that still listen to a lot, not the 22-year-old they wish still did.

Here’s the rub.

The older you get, the less time you devote to music. You typically get to know fewer new songs, take longer to warm up to those new songs you do like, and continue liking those songs longer than you would have in your youth. Those tendencies are reflected in the results when stations survey older listeners in their music research.

2) Radio has lost the hard-core music utility listener.

If you grew up after Napster, you can’t imagine how it sucked to be a voracious new music fan in the 90s. You’d spend $33.64 in today’s money on an entire CD, sometimes just to get one good song. That left broke young music fans relying on their favorite local FM radio station to hear the songs they couldn’t afford. You didn’t care about the DJs or the contests or the morning show skits. You just wanted to hear “Sateria” because you blew your budget on Pinkerton.

Today, that money buys you two months of access to the entirety of recorded hit music. As soon that Spotify and the iPhone made that option possible, the listeners who simply used radio as a music utility bailed.

Meanwhile, callout research has for decades only surveyed respondents who say they spend significant time listening to the client station. Before streaming, that ensured callout included rabid music fans. Nowadays, recruiting listeners who express loyalty to the station gets you folks who like the morning show, or the DJs, or who simply aren’t big enough music fans to fool with CarPlay.

Paradoxically, this combination creates a doom loop that makes radio even less attractive to the listeners who still want to hear songs from this year. As I outlined in Is Research Ruining Radio, recruiting fans of the station’s core music genre could make callout research more relevant in today’s streaming-first era. I offer several suggestions for fixing callout in that article.

The next three reasons, however, are issues fixing callout can’t fix:

3) It’s been a terrible year for new hit music.

In 2024, Chappell Roan, Sabrina Carpenter, Shaboozey, and the aforementioned Hot 100 squatters Teddy Swims, Benson Boone, and Lady Gaga all had massive hits. In 2025, they all released anxiously awaited follow-up tracks that flopped. As I showcased in Why Are So Many 2025 Follow-Ups Flops, fans simply have more fondles for a great tune from last year than a boring one from this year.

4) We’re in a very adult-driven music cycle.

In oversized SUVs in front of America’s high schools, Moms wait for their students enjoying Benson Boone, Teddy Swims, Lady Gaga, and Alex Warren on the local Top 40 station. The teens they’re picking up might not hate these songs, but they’re not the songs they’ll play on their phones when they get home or at their high school reunions. When the Adults Pick the Hits, it creates really boring eras in Pop music.

5) Gen Z hasn’t yet made its musical mark.

Today’s high schoolers and young college students are a distinctly different generation than the Millennials who came before them. However, they haven’t yet reached critical mass of replacing them as the primary consumers of new music.

History suggests that day is almost here.

As I detailed in The Generational Music Theorem, when a younger generation replaces an older generation in picking the hits, they launch an evolution that makes Pop music fun and mass-appeal again—saving us from those boring Adult-driven hits. Want a sneak peak of what Gen Z will embrace?

What streaming can tell radio about recurrents

Until streaming; we never knew how often people kept playing their favorite songs as those songs got older and older.

While callout research revealed that fans still love a song long after people stopped buying that song, streaming shows that just because people still love a song doesn’t mean they want to hear it as often as they once did.

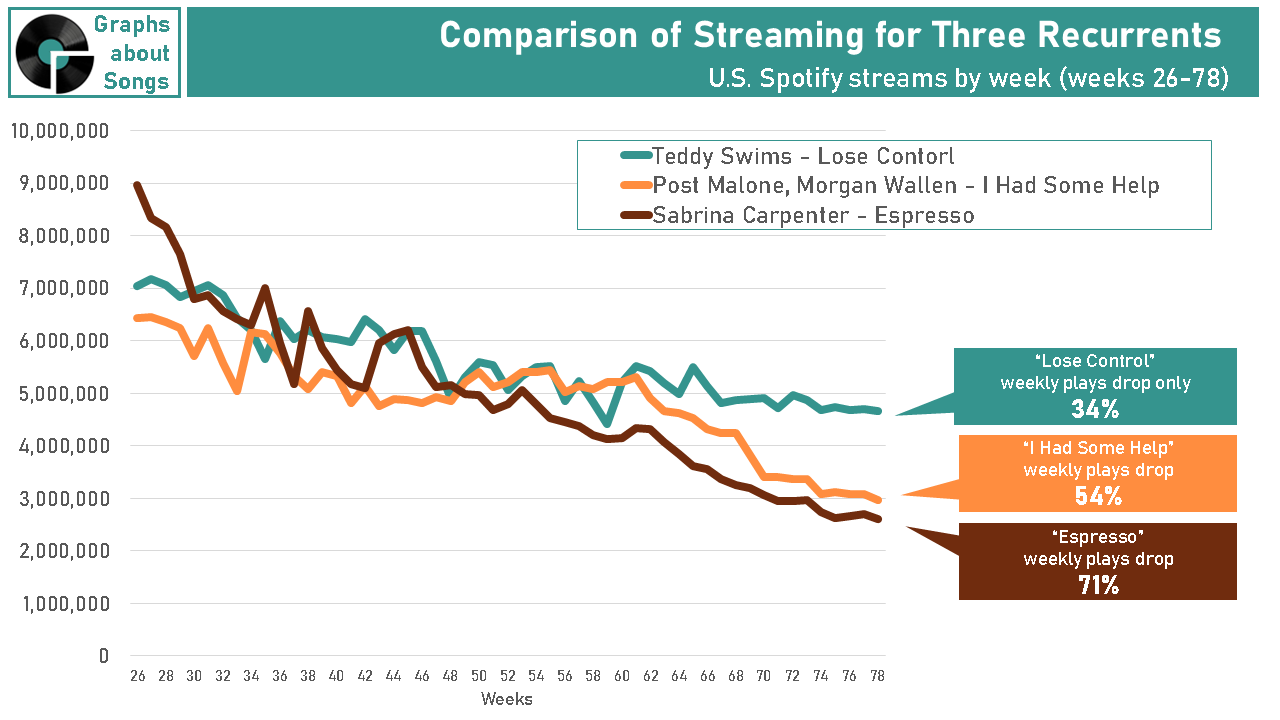

Consider three of 2024’s biggest hits, “Lose Control, “I Had Some Help”, and “Espresso.” The chart below shows weekly Spotify streams for the year after these songs were at their peak as current hits—specifically week 26 (the half year point) to week 78 (a year later).

While all songs see their weekly plays decline with each passing week, some songs’ streaming fall off faster than others.

Some songs see a particular point where weekly streaming suddenly drop off faster than before, indicating fans are growing increasingly tired of that song.

“Lose Control” has had a longer self life than both “I Had Some Help” and “Espresso,” both of which saw weekly streaming accelerate its decline after 62 weeks.

If your local hit music station let streaming data insights guide how often it plays these recurrents, you’d still hear Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” from time to time.

But you wouldn’t hear it enough to make Billboard fundamentally change the Hot 100.

(If you’re curious how I help radio stations use music consumers’ actual listening behavior to pick the most popular hits, drop by Your Hit Momentum Report.)

Further Reading referenced in this article:

Data sources for today’s post:

RAMP: Radio and Music Pros: https://ramp247.com/ (Source for Coleman Insights’ Integr8 USA National Callout data for Top 40 and Hot AC)

The Billboard Hot 100: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100

Spotify 200 Weekly Charts (2034-2025 for the USA): https://charts.spotify.com/charts/overview/us