Is Research Ruining Radio?

For decades, radio has used a marketing research tool to pick which hits to play. Lately, that research keeps the same few songs atop the charts for months. Is this tool killing radio?

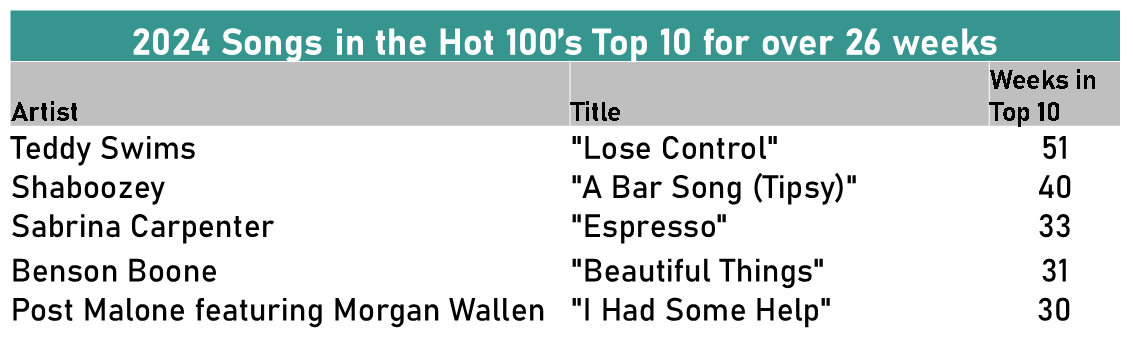

In a previous post, I examined how Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” became Billboard’s 2024’s Song of the Year not through cultural relevance or musical innovation, but simply because people keep streaming it month after month.

It’s among just five songs that took up permanent residence in the Hot 100’s Top 10 last year, a trend that’s only emerged as streaming music replaced buying it.

It’s not just streaming that keeps these songs at the top of the chart for unprecedentedly lengthy periods.

In today’s Part II of “Do You Have To Let It Linger,” I’ll explore FM radio’s role in keeping a handful of songs atop the Hot 100 chart forever.

Specifically, I’ll examine how the professional music research that radio uses has made radio slower than ever to add new songs and even slower to move on from the biggest hits. The result is a small handful of songs that seemingly stay around forever.

If you’re a fellow music geek, you’ll get a behind the scenes look at the tools your local radio station uses to pick the hits.

If you’re a radio programmer, we’ll tackle some tough dilemmas you face about how—and if—you should keep using those time-tested tools.

Before we dive in, a bias disclosure: I spent 15 years leading Coleman Insights’ Integr8 New Music Research division. My job was helping contemporary radio stations design music research and interpret the results. If you’re hoping this post will bash radio’s researchers and consultants, you’ll be disappointed.

Radio’s Album Track Crisis

In 1972, radio programmer Buzz Bennett had a problem: Like every station since Top 40 Radio and Rock ‘n’ Roll co-emerged, he relied on asking local record stores about their 45 rpm sales to know which songs he should play on his station—KCBQ San Diego to be specific.

But now, folks skipped the 45s and instead bought entire albums.

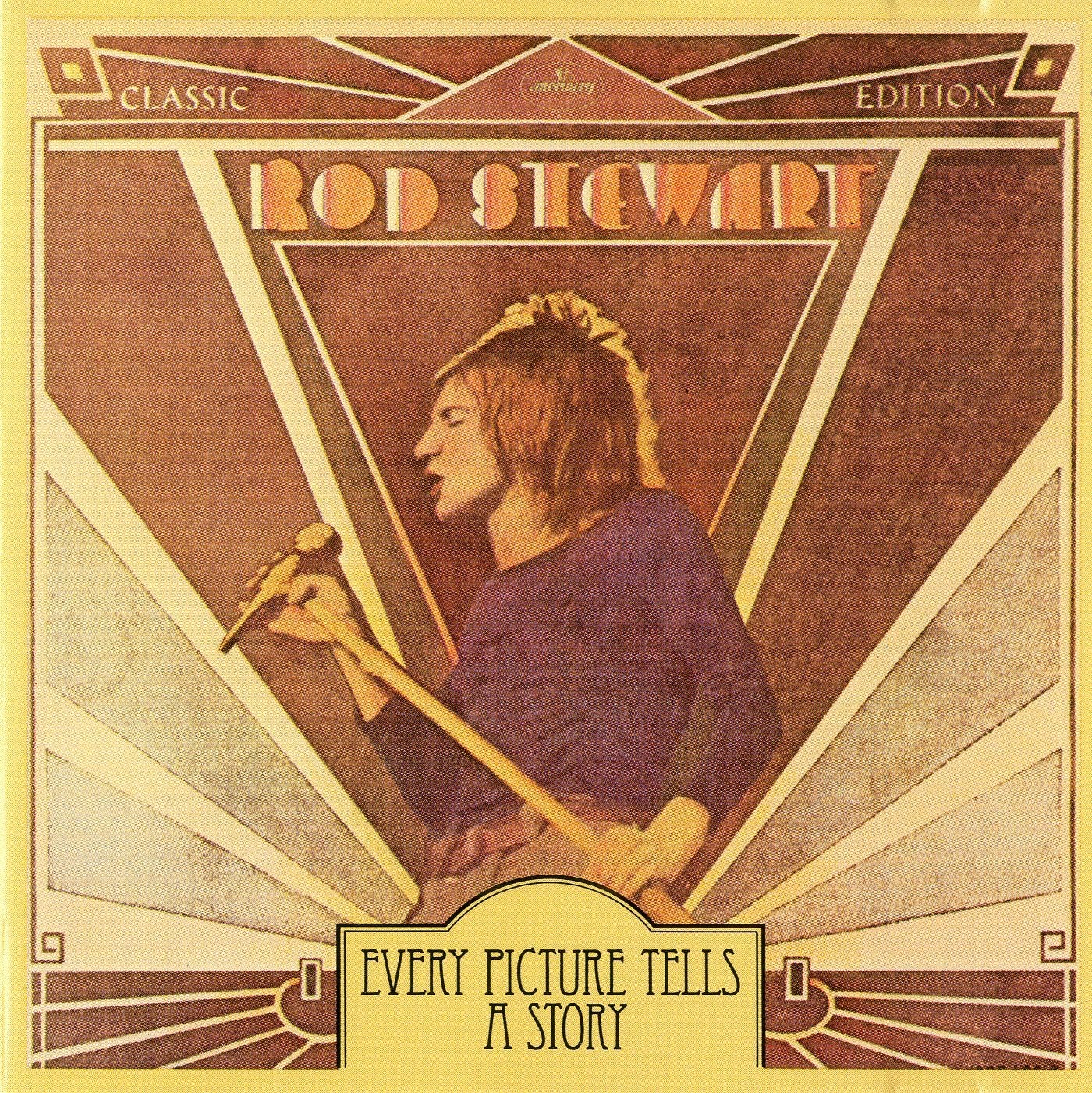

It started with the artists we now call Classic Rock—Think The Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band or Tommy from The Who. The artists featured on the underground FM “Album Rock” stations transformed the LP from a collection of past hits to a congruent work of art.

By the early 1970s, even mass-appeal Pop artists on Bennett’s AM Top 40 station were selling more albums than singles: Carole King, Stevie Wonder, Elton John Bill Withers, The Rolling Stones, and Chicago were all releasing legendary, top-selling albums.

His problem? Which song did they really buy that album to hear?

He knew Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story was a top seller—but were his listeners buying it for “Maggie Mae” or “Reason To Believe”, or "(I Know) I'm Losing You", the single the record label originally released?

Unlike other programmers, Bennett had a master’s degree in marketing. One night, Bennett was sitting around with three other radio professionals when he let loose his academic knowledge of research methodology to brainstorm how marketing research techniques could help his station know which track on the album was the real hit.

What emerged from that brainstorm was callout research.

The Dawn of Callout Research

The premise of callout research is simple: If you want to know which songs your listeners know and love most, just ask them.

The cheapest and most reliable way to do that was to “call out” to random phone numbers in your city. (Not only did Americans all have a home phone back then, they actually answered it.) If they got someone the right age and who listened to their station, they’d play recognizable snippets of 20 to 30 current songs down the phone line, ask if they were familiar with each song, and if so, how much they liked or disliked it.

By the late 1970s, callout research wasn’t merely a solution for the biggest hits on best-selling albums, it was a secret weapon innovative programmers used to win fierce ratings battles.

Callout research also spawned some unexpected discoveries that still hold true today:

Three Things We Accidentally Learned from Callout Research

These three findings were revolutionary in the 1970s, and yet still remain valid today:

1) Listeners still love a song long after people stop buying it.

When your mom turned on her favorite Soft Rock station or while waiting for your dentist, were you ever subjected to Chicago’s 1976 ballad, “If You Leave Me Now?” Those of us old enough to remember our first Walkman recognize those lush horns that start the song instantly.

“If You Leave Me Now” is one of the first songs callout research kept on the radio for years.

In November 1977, Billboard Magazine’s Claude Hall examined the role of radio’s new “passive” research. Jeff Salgo, program director for San Bernardino’s Radio 59 KFXM, noted that Chicago’s plea to “ooh oh oh oooh, baby, please don’t go” was still their listeners’ #1 most loved song after 13 months.

[I]t's a whole false premise about looking at just record sales to determine what to play on the air. Sales, of course, are a great initial indication of when to start playing a record. but no way to tell when to stop playing it. You may need to keep playing it long after sales have stopped or tapered off.

Not all songs have such staying power. Salgo noted that listeners started getting sick of Alan O’Day’s contemporaneous “Undercover Angel” after about 20 weeks. Both “If You Leave Me Now” and “Uncover Angel” spent about the same time in the Billboard Hot 100’s Top 10 based primarily on record sales. However, Chicago has over three times the staying power.

This finding gave rise to what radio programmers call a “recurrent”---a song that listeners no longer think of as new, but that listeners still love. Before callout, when people stopped buying a song, radio simply stopped playing it. The song vanished, never to be heard again until occasionally coming back as a rarely played “gold” title.

Just because listeners still love a record long after sales stopped, however, doesn’t mean listeners want to hear it as often as they did when it was fresh. Jeff Salgo added

We just can’t have a chart that reflects airplay totally because ‘If You Leave Me Now' would be Number One. So our playlist is a mixture of everything.

Remember this tenet when we get back to our discussion of Teddy Swims.

2) Most people are “passive” music consumers

Callout revealed there are two types of music consumption: “Active” and “Passive”:

Active consumption is when someone went down to Sears and bought the brand-new album from their favorite artist. Today, it’s when someone samples a new album on Spotify the day it drops. I call then Artist Stans.

Passive consumption is a radio listener who didn’t seek out a new song but came to love it after hearing it on their favorite station. Contrary to pundits, that scenario still happens today and is exactly how many folks discovered “Lose Control. I call them Casual Fans.

One of the first radio programmers to embrace Callout research was Bob Pittman. (Yes, the Bob Pittman that now runs iHeart Radio. And yes, the Bob Pittman that launched MTV.) Back then, he programmed New York’s 66/WNBC (Yes, the WNBC that later hired—and fired—Howard Stern), Pittman asserted that only 5 percent of radio listeners actually buy records.

[So] while WNBC is also calling that 5 percent of “active" listeners, it’s also calling the 95 percent of “passive” listeners who don’t buy records.

Another now legendary radio programmer, John Sebastian, estimated that only about 20 percent of radio listeners are “active” consumers:

For so long. radio has been gauging itself from only about 20 percent of the total programming universe-people who buy records and people who request records.

(Sebastian would soon take his success at KDWB Minneapolis to land the programming role as Los Angeles’ 93/KHJ.)

Not all songs have comparable active and passive fan bases, however. Jeff Salgo noted:

[T]here are records that were not store hits. but were passive. Passive, of course, being the wrong term because people liked them but perhaps didn't go buy them.

Judy Collins’ “Send In The Clowns” was only a modest hit in 1975 based on record sales, but did receive airplay from some FM Album Rock stations (Yes, the same format that brought you Led Zeppelin.) Two years later, callout research in several cities identified it as a highly popular song among radio listeners.

Thanks to the newfound radio airplay, “Clowns” became an even bigger hit in 1977. John Sebastian comments:

{Q]uite often, we find out that the number one song in sales is not necessarily the best song to be playing. or certainly not the song to be playing in hot rotation. Sometimes. also, a song that peaks at mid-chart position might be the one you should play on the air more often.

That lesson is even more important today, as streaming data inherently amplifies “active” fandom—including for songs that will never become mass-appeal hits.

3) Passive consumers can’t tell you what they’ll like until they hear it—and they have to hear it a lot.

John Sebastian asserts:

I don't believe you can locate totally new music from callout research. since you’re reaching both passive and active listeners.”

Song sales of yesterday and Spotify binge sampling today are instant, since an artists’ active fans know about new releases and seek them out.

In contrast, passive fandom only develops when someone else plays the song for you---including your favorite radio station. Callout revealed that it can take weeks or even months for a passive fan to get to know a new song and ultimately decide if they like it.

No. ifs not valuable at all for finding new music. But it will tell you if a record is alive in your market and if you should be playing it.”

Callout Research Impacts the Hot 100 Chart

By the late 1980s, callout was no longer just a new “secret weapon” for a few innovative programmers. It had become the standard tool for radio to pick which songs to play

When the Billboard Hot 100 switched from self-reported playlists to electronically monitoring which songs radio played and exactly how often they played them, the impact on the average age of a top 10 song immediately lengthened from five weeks in 1991 to eight weeks in 1992:

Before the impact of callout research fully impacted reported airplay, it was almost unheard of for songs to remain in the Hot 100’s Top 10 for more than three months. That changed overnight:

As Radio Became Fragmented, Research Became Focused

It wasn’t just Pop hit stations using callout, either. Country, Rock, and R&B stations used it, too.

As radio formats became more fragmented musically, callout research got pickier about respondents. In the 70s, you merely had to listen to the station to participate, By the 90s, callout research also recruited people who said their favorite station was the client station. Stations further focused their research on respondents who reported spending many hours a week listening to their station.

Focusing on people who listen most to your station and listen a lot makes sense. These heavy users are the ones that have the greatest impact on your ratings.

It helped stations win ratings battles for decades.

However, this logical focus on the radio station’s most ardent fans may now—in the streaming era—be callout research’s albatross.

Callout Research Today

No one calls listeners in 2025. Like all polling, radio research now recruits and surveys listeners online. However, radio people still call it callout and the fundamental premises have remained unchanged since the 1990s. It still recruits listeners who are:

within the station’s demographic target audience,

listen to and prefer their station

are heavy users of FM radio.

It still plays listeners snippets of songs and asks if they know them and how they’d rate them.

So what specific songs does callout research say are America’s biggest hits?

Coleman Insights’ Integr8 New Music Research (see disclosure above) is among the leading providers of callout research, On Wednesdays, they publish the three best-testing songs from their nationwide research in the RAMP (Radio and Music Pros) newsletter.

Back in September, Shaboozy’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” was among their three highest rated titles in their survey for CHR stations.

On February 10—five months later—“Tipsy” is still their best-testing title. It’s been over nine months since Shaboozey first entered the Hot 100’s Top 10.

In Integr8’s Hot AC survey, a format that focused on the hit songs slightly older adults love most, Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” was the #1 back in September.

As of February 10, it’s still #1. The song has been a hit for well over a year now.

In fact, in every Integr8 USA Hot AC survey since September, The top three songs have been the same:

Teddy Swims - Lost Control

Benson Boone - Beautiful Things

Shaboozey - A Bar Song (Tipsy)

There’s no question these songs are all mass appeal hits, as I showed when analyzing streaming in Do You Have To Let It Linger, “

The graphs below show two ways of measuring each song’s streaming performance:

The teal line graph shows how many plays the song received from week to week on Spotify in the U.S.

The color-coded bar graphs show each song’s Momentum IndexSM. That’s a proprietary measure I developed for The Hit Momentum Report to help professional programmers know which songs on Streaming actually have large passive fan bases. (Details are here.) For now, just know that green bars turning into yellow bars indicate the point in time when listeners are streaming a song less often because they’re getting tired of it.

“Lose Control” was never among Americans’ most streamed songs on any given week. However, it was Billboard’s 2024 Song of the Year because people kept streaming it. Over a year later, fans still show no signs of being sick of it.

People also kept streaming Benson Boone’s “Beautiful Things,” only showing signs of tiring of it in early January 2025:

So far, streaming data fully validates callout research.

Things look a bit different when we dive into Shaboozy’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” however: Spotify streaming patterns suggest listeners were getting tired of Tipsy back in October 2024. Sure, listeners still love it—but streaming behavior suggests they haven’t found it relevant in months.

Perhaps more eye opening is how long it takes songs to reach the callout research penthouse these days.

Consider “Die With a Smile” from Lady Gaga & Bruno Mars, which has garnered over 10 million streams on Spotify almost every week since August 2024. It’s undoubtedly still a highly relevant hit. However, “Die” didn’t reach the Top 3 of Integr8 USA until February 2025 after 25 weeks.

Or consider Myles Smith’s “Stargazing.” It finally reached Integr8 USA’s top 3 for their report dated February 10. That’s three weeks after it dropped out of Spotify’s Top 200 after 33 weeks.

Here’s the vintage of the Top 3 songs in a typical week for Integr8 USA’s Top 40 nationwide callout, based on their findings from September 2024 through February 2025: The average Top 3 song since September has been in the Hot 100’s Top 10 for 32 weeks.

Integr8 USA’s Hot AC research, which focuses on the hits that adults slightly older than the typical Top 40 listeners like, is even slower to crown its champions:

Yes, I’m admittedly biased, but I can assure you that Coleman Insights thoroughly vets respondents to make sure they’re legitimate listeners. Their national research includes a statistically sufficient sample size. Their research accurately reflects what it claims.

And yes, callout research has always been slower than other metrics for new songs to become popular and for hit songs to become unpopular—specifically because it’s gauging passive music fandom and not just active music consumption.

But it used to take six weeks for a song to reach the top—not six months.

What changed?

The correct question is perhaps what hasn’t changed.

Why Callout Keeps Songs on the Radio Forever

Historically, focusing on radio’s heaviest users produced a full spectrum of the most active to the most passive music consumers because radio listening used to correlate to music engagement. It was that complete spectrum of music consumption—not radio usage itself—that made callout a reliable tool for radio airplay.

However, streaming has destroyed that correlation between perceived radio usage and actual music engagement.

#1 Callout increasingly reflects the most disengaged music consumers.

From its inception, callout research was the sole tool for measuring passive music fandom. Yes, some respondents would inevitably be active fans of some songs. The net result—as future MTV programmer Bob Pittman noted way back in 1977—was callout reflecting a mix of active and passive fandom. That mix accurately reflected radio’s audience.

However, a key component of callout research is now skewing that balance towards only the most passive music consumers.

Almost every callout research survey requires you to say you listen to their station. If you don’t mention it, you’re out.

Additionally, a major share of respondents must also say you’re the station they listen to most.

Finally, most require you to report listening to their station for a specific length of time each week

It makes perfect sense that you want to keep your biggest fans happy.

However, that’s looking at things from a radio perspective, not a music consumer perspective.

Back in the 1990s, if you spent a lot of time listening to your favorite radio station, you were also a heavily active consumer of music in general. You bought CDs. You went to concerts. You even called your favorite station and made requests.

In the 2010s, music’s most active consumers were the first fans to abandon radio for streaming---or at least they no longer express strong loyalty to radio---even though many do in fact still use radio. In fact, 82% of Americans do each week, according to Nielsen.

Edison Research—a highly respected competitor to Coleman Insights—showed just how rapidly Americans replaced radio with streaming as the place to go for new music:

By taking a radio-centric approach to respondent recruitment, callout research increasingly excludes all but the most passive consumers of new music.

That means they’re talking to the people least likely to have heard the new songs that more engaged music fans already know. They’re also the most likely fans to still enjoy older songs that those more engaged fans already grew tired of hearing.

That keeps “Lose Control”, “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” and “Beautiful Things” atop callout reports forever, while potentially ignoring the increasing number of songs that gained relevance without radio exposure, such as Chappell Roan’s “Hot To Go!”

That’s dangerous.

As more active music consumers sample FM radio and hear songs they moved on from months ago, they’re even quicker to turn off the radio and connect the Bluetooth.

#2 As radio audiences age, so do research respondents

It’s no secret that the younger you are, the less time you spend with FM radio these days. Logically, many programmers seek to satisfy the audience they do have, not the one they might wish they still had.

Here’s why this perfectly sound logic is wrong.

Musical trends always start with young people and filter up. It’s a lot easier to get a 48-year-old into Chappell Roan than a 22-year-old into Madonna.

Back in the day, 13- to 29-year-olds drove Top 40 ratings. Nowadays, as younger people spend less time with FM radio, its adults in their 30s and 40s determining the fate of hit music stations’ ratings. Logically, stations seek to make these remaining listeners happy by focusing their music research on increasingly older adults.

Unfortunately, recruiting older listeners makes the “slowness” even worse, because the older you are, the slower you become familiar with new songs and the longer it takes you to get sick of older ones

The bigger problem, however; it’s still those teens and young adults who set the tone for what music is popular—even for older adults.

Billie Eilish, Lil Nas X, Olivia Rodrigo, and Chappell Roan are hitmaking artists that were massively popular among listeners under age 25, while adults over 25 remained oblivious to them for months. Eventually, however, each one became a mass appeal artist.

“I skate to where the puck is going to be” is Wayne Gretzky’s famous mantra for winning in hockey. Smart stations survey younger listeners to know where music is going to be.

Is Slow Research Even a Problem?

After all, the research reflects what radio users like, which are the same songs Spotify users keep playing forever. Is playing a few big hits for many months really hurting radio?

Yes—if we want radio to remain a viable medium for contemporary music consumption among people who actually like music.

#1 People pick a hit music station because they want to hear what’s relevant right now.

Sure, folks want to hear songs they know and love—and some tune out when they hear a song they don’t yet know. However, people don’t choose a radio station with a contemporary format because they want their all-time favorites.

They want hit music radio to keep them in touch with today.

As I showed in Once Upon a Time when Radio Played New Music, leaning too much on last year’s proven hits doesn’t cost you listeners today. However, “hit” music stations that focus too heavily on well-worn favorites ultimately lose listeners tomorrow.

Why? Because your listeners begin perceiving you’re stale and out of touch.

#2: Active music consumption is bigger than ever

While radio’s primary research tool is—inadvertently but increasingly—focusing on the most passive music consumers, active music consumption is bigger than ever thanks to streaming.

Back in the 1990s, the guy who bought a lot of CDs also listened to his favorite radio station a lot. There were only so many CDs you could buy at those prices. Radio gave you the rest for free.

Now of course, you can check out any new song you want for the low monthly fee you already paid Spotify.

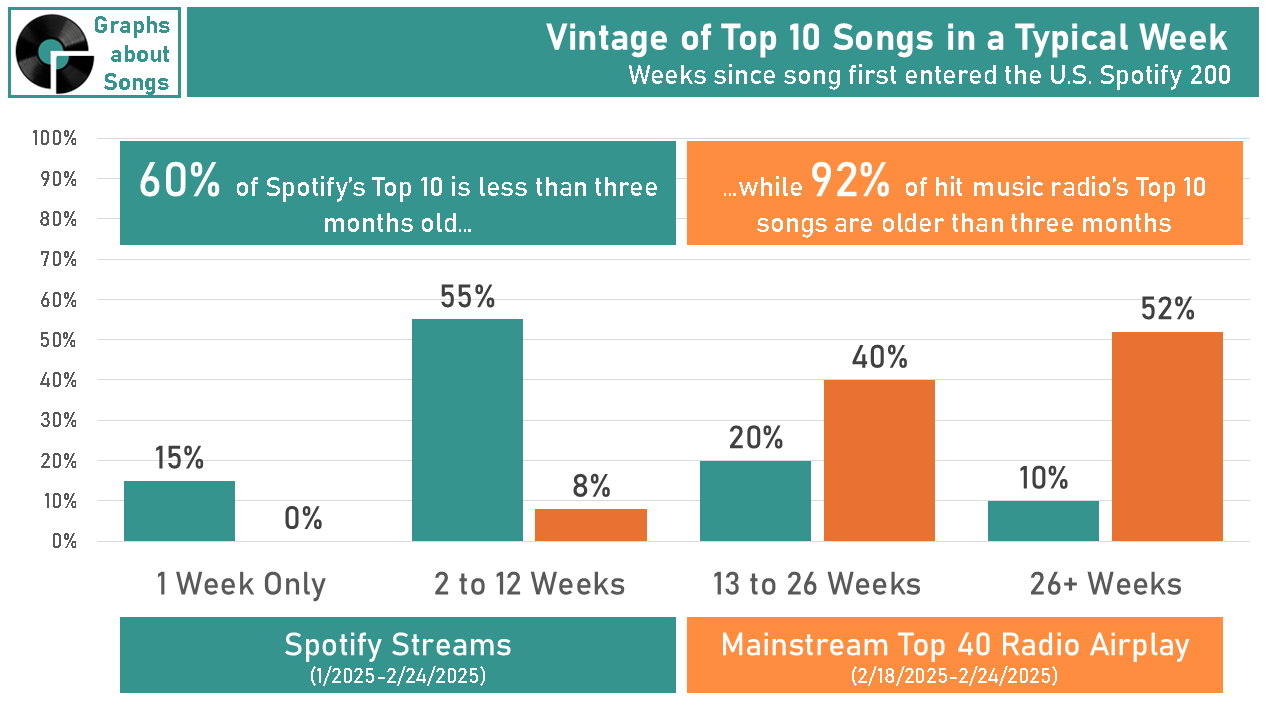

Consider the vintage of the typical Top 10 songs on Spotify in the U.S. compared to the Top 10 songs you’ll likely hear this week on your local hit music station. Yes, streaming data does amplify active music consumption—but it also enables it:

As I noted in The Advent of Binge Listening, the ease with which music fans can sample new music may endanger radio’s tactic of only playing one song from an album at a time. Chappell Roan’s “Pink Pony Club” has only now become a big hit on Top 40 Radio.

For the fan who discovered Roan last year, that song is already nine months old.

So What Should Radio Do… and Why?

I still believe there’s a role for traditional callout research. Asking people what songs they know and love is simply the most direct way to know what songs people know and love.

However, research firms need to evolve their practices to capture the full spectrum of relevant music fans, not simply the most passive and disengaged music consumers.

Meanwhile, radio stations need to fully tap into the wealth of streaming data available showing the songs listeners choose when they’re in control of their music—especially for new releases that callout research can’t gauge. (I can help you there.)

Look, I’m a unabashed radio fanatic. I believe in this magical medium where good friends have shared great music with me throughout my lifetime. As our world becomes all about A.I and algorithms, a real person sharing hand-picked music could be the oasis we’ll desperately need.

If radio has any hope of remaining relevant in a world of content abundance, however, those stations promising today’s music need to offer curated music experiences that truly reflect today.

Not last year’s five biggest hits.

Want more Graphs About Songs?

Select “NONE” and get Graphs About Songs in your inbox for FREE.

If you program pop music for a a living, selecting a paid “Monthly” or “Annual” subscription also gets you The Hit Momentum Report, my weekly analysis of which songs 83 million American Spotify users say are hits

Data sources for today’s post:

RAMP: Radio and Music Pros: https://ramp247.com/

The Billboard Hot 100: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100

Wikipedia’s Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 singles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles

Mediabase - Published Panel - Past 7 Days: http://www.mediabase.com/mmrweb/fmqb/charts.asp?SHOWYEAR=N

Spotify Charts (2024-2025 for the USA): https://charts.spotify.com/charts/overview/us

Fascinating article! Love the history lesson and caution here.

Terrific article. Sign me up as the person who listens to radio when I'm looking for new music to buy. (Billboard and iTunes could really improve in this area.) I purchase around 300 songs a year on iTunes...and many I find on artist X/Twitter accounts. Some of my favorites last year from following the artist on X are: "Thought About You" (Love and Theft), "Each Moment" (Kathy Troccoli), and "Time Well Wasted" (The Fray). My favorite song lately is Burton Cummings "A Few Good Moments". My personal pattern is play a song for about 6-8 weeks...then move on. Many of the songs you used in the article would cause me to change the station now but not a year ago when they first were released. Anyway, appreciate your information...learned a lot.