Does The #1 Song Even Matter Anymore?

Streaming has fundamentally changed how we measure music consumption. Has it also ruined the cultural relevance of having a "hit"?

So many of my fellow chart geeks complain how it’s futile making comparisons between how today’s hits perform on the Hot 100 compared to yesterday’s classics

When The Beatles famously owned all top five slots on the Hot 100 in 1964, we believed it would never happen again. Now, Drake does it all the time (assuming Kendrick Lamar doesn’t kill his career.)

In 1983, Michael Jackson’s Thriller spawned a record seven Top 10 singles. Each one remains familiar and beloved. Today, Taylor Swift drops an album and takes over the top of the Hot 100 with every track—including deep cuts even Swifties won’t remember.

As radio consultant and music guru Sean Ross noted on (what was then still) Twitter, “[It’s] been a long time since I thought the top seven were symmetrically the seven most-loved songs.”

Ultimately, these anecdotes tie back to—wait for it—streaming. More specifically, how streaming has slashed the longstanding link between songs with the biggest consumption and the songs with the biggest cultural impact.

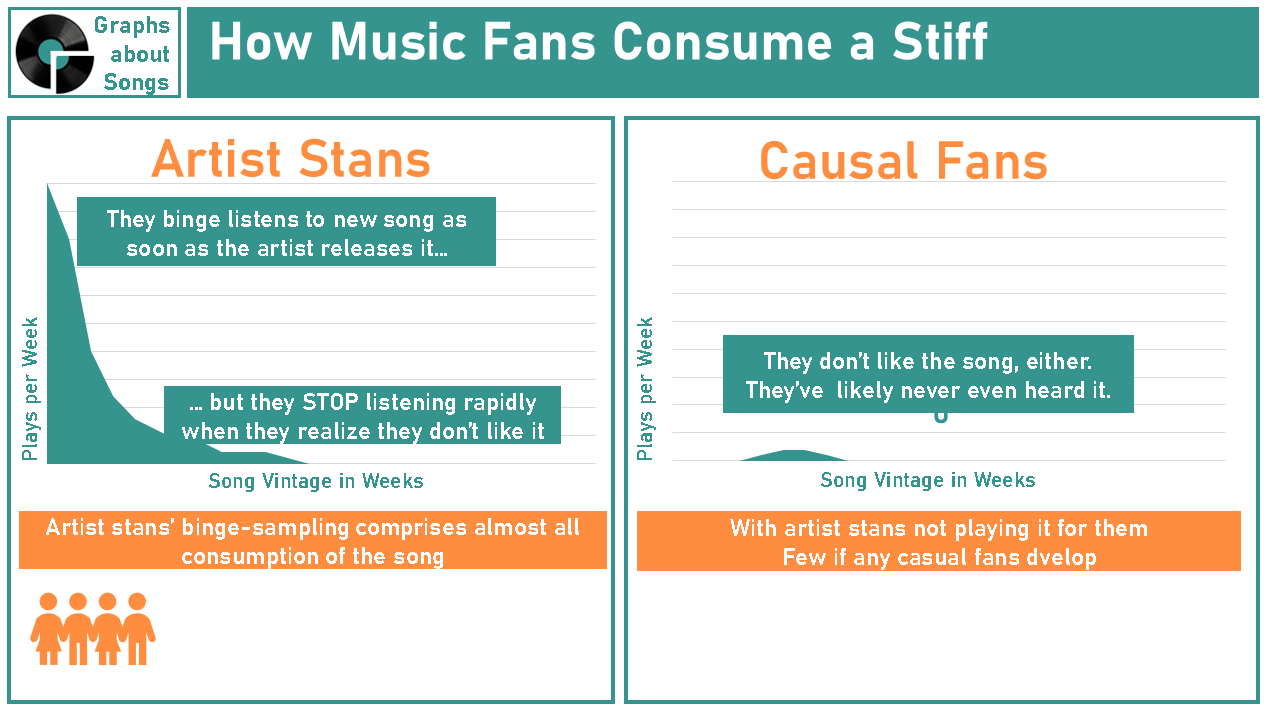

Artist Stans vs. Casual Fans

With their Hot 100 chart, Billboard’s goal has always been to create a ranked list of total music consumption in the U.S. That music consumption comes from two different patterns of music consumption; Artist Stans and Casual Fans:

For any song that has a massive cultural impact (a.k.a. “a hit”), the song ultimately has many more Casual fans than Artist Stans.

In the beginning, however, the Artist Stans listen to the song a lot.

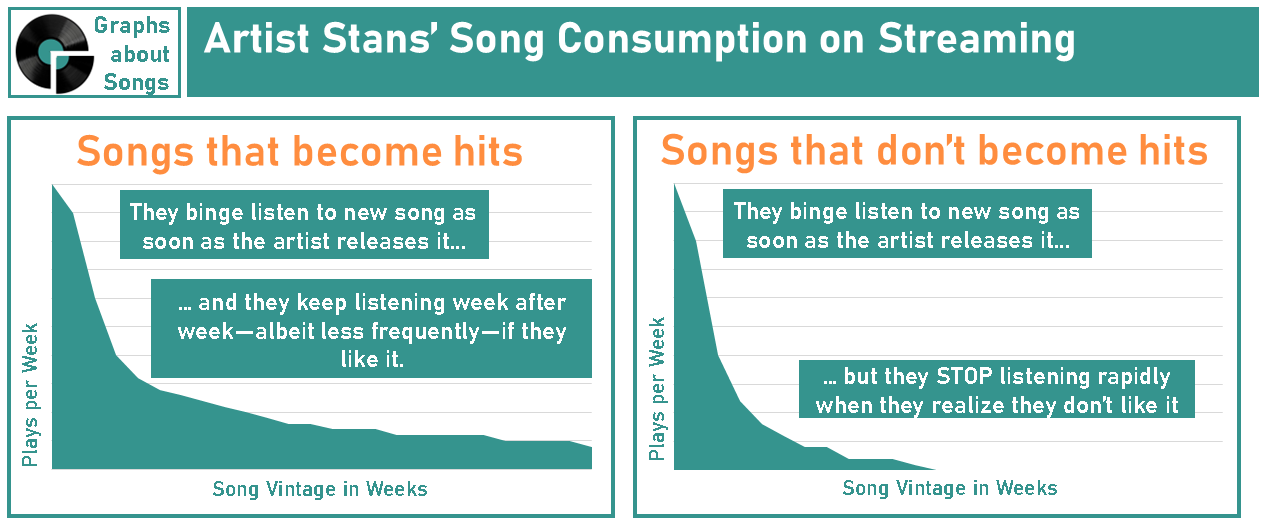

What about songs that don’t become hits? If the artist has a big fan base, those Artist Stans will still binge it heavily when it drops. But their play counts for the song will rapidly decline if they hate it---and without Artist Stans (or radio) promoting it, Casual fans won’t ever even hear it.

Notice how Artist Stans’ consumption of songs that endure looks the same as their consumption of songs that don’t during the week the song is new? Keep that fact in mind when we discuss streaming…

Finally, note that Artist Stans and Casual Fans are not specific people. Instead, they’re how a person consumes an individual song. Even the biggest music geeks will have a small number of favorite artists whose music they seek out when it’s new, while enjoying a far greater number of artists and their songs when they discover them along the way.

Historically, buying music measured Artist Stans and radio measured Causal Fans

Until the proliferation of streaming, we measured Artist Stan style consumption by measuring music purchases and we measured Casual Fan style consumption by measuring radio airplay.

From the advent of the 45-rpm single in 1949 to the waning days of iTunes’ relevance, Artist Stan consumption is strongest the week a song debuts. The chart below examines the top 10 paid digital downloads the final year iTunes was more relevant than Spotify, but the pattern of purchasing music on physical media was comparable.

Likewise, the pattern of Casual Fans style consumption, as measured by radio exposure, has remained remarkably consistent ever since the widespread adoption of professional music research in the 1980s. For decades, new music stations have conducted surveys to learn how many listeners know each song and whether they like or dislike it. Using this survey data, radio gives the most exposure to the songs the most listeners know and love.

Since it takes time for a mass audience to get to know and love a song, radio airplay—and thereby Casual Fan consumption—typically takes two months to develop.

The chart below measures how old the 40 most-played songs on America’s Contemporary Hit Radio (CHR) stations were for a typical week. It would have looked remarkably similar in the 1990s as it does in the 2020s.

What about streaming?

It’s complicated—and we’ll get to why—-but on the surface, the top 10 songs on Spotify look a lot like the top 10 songs looked on iTunes.

iTunes removed barriers for Artist Stans to sample new songs…

There have always been Artist Stans. They rushed to Woolworth’s to buy Beatles 45s. They bought Garth Brooks’ No Fences CD at Walmart.

While the pattern of when Artist Stans consume new songs hasn’t changed, the barrier to consuming music as an Artist Stan was higher during the physical media era. The 45 of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” could cost up to $9.87 in today’s money. A CD in 1991 could cost $29.96 today. Choosing between Nirvana’s “Nevermind” and Pearl Jam’s “Ten”? The struggle was real.

iTunes eased that burden when you could once again buy a single, download it instantly, and do so for only 99 cents. “I Gotta Feeling” was yours instantly for only $1.45 in today’s money. Suddenly, a lot more people bought songs as soon as they dropped, without even bothering to listen to them first.

iTunes didn’t change when an Artist Stan bought a new song. It simply made it possible for more Artist Stans to buy it.

… then streaming smashed the barrier

Streaming further lowered the burden of sampling new releases. Now, you don’t even have to pay for the song; it’s covered in your Spotify subscription or by the ad you watched on YouTube.

Streaming also fundamentally changed how we measure music consumption:

If you bought the 45 of “She Loves You,” it counted as one purchase.

If you (legally) download Katy Perry’s “Hot ‘n’ Cold”, you counted as one purchase.

When you binge streamed Taylor Swift’s “Fortnight” ten times when Tortured Poets department dropped, you counted as ten plays.

By lowering the barriers to accessing new songs, and by switching from measuring how many people buy a song to how many times people play a song, Artist Stan style song consumption has increased throughout this century.

You see the impact of these changes when examining the typical vintage of the top 10 songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 during different eras:

During the SoundScan era of the 1990s, only 7% of Top 10 hits stayed in the Top 10 for only 1 week.

The iTunes era (2006-2017) raised that number to 16%.

When streaming became the dominant platform for sampling new music, however, the percentage of top 10 hits that were only in the Top 10 for one week skyrocketed to 40%.

(I covered how the Billboard Hot 100’s chart methodology has changed over the years in the post Why it’s so hard to know what’s really a hit today. Check it out if you want more info on these three different eras.)

How Streaming Ruined The #1 Song

Which brings us back to those elite songs that reach #1 on the Billboard Hot 100, a illustrious and often elusive honor that signifies you’ve recorded a hit.

#1 meant everyone’s heard your song, whether they wanted to hear it or not.

#1 meant your song was a part of the cultural Zeitgeist.

#1 meant your song was probably destined to play at a class reunion in 20 years.

A #1 song also meant your song likely remained a top 10 hit for months—or at the very least—a month.

For the first 60 years of the Hot 100’s history, only three songs reached #1 on the Hot 100 that stayed in the Top 10 for less than four weeks:

In 1974, John Lennon’s #1 "Whatever Gets You thru the Night" only stayed in the Top 10 for three weeks. It’s not one of Lennon’s most well remembered hits, but it was at least briefly inescapable.

In 2004 and 2006, respectively, American Idol contestants Fantasia and Taylor Hicks each had #1 songs that only lasted in the Top 10 for two weeks. These #1s exclusively have iTunes downloads to thank. Neither song received wider exposure and no lasting cultural impact. However, early American Idol itself did have mass appeal cultural relevance.

Since 2019, however, twenty different #1 songs on the Hot 100 have remained in the chart’s top 10 for less than a month. Nine of those #1s were only in the Top 10 for their one week at number one.

Those songs are from artists with massive fan bases, including Taylor Swift, BTS, Drake, Ariana Grande, The Weeknd, and Megan Thee Stallion. These twenty songs aren’t the ones even the fans will remember.

Streaming mixes Artist Stans’ and Casual Fans’ consumption

Remember how the Hot 100 balances Artist Stans and Casual fans to create a total snapshot of the songs Americans consume? Historically, song sales gauged Artist Stans’ consumption, while radio airplay measured how many casual fans heard each song.

Streaming smeared that divide.

Both Artist Stans and Casual Fans use Spotify and its competitors to enjoy music. As noted above:

The Artist Stan is the Swiftie who binged The Tortured Poets Department last April.

The Causal Fan has “Cruel Summer” in a playlist after hearing it on the radio.

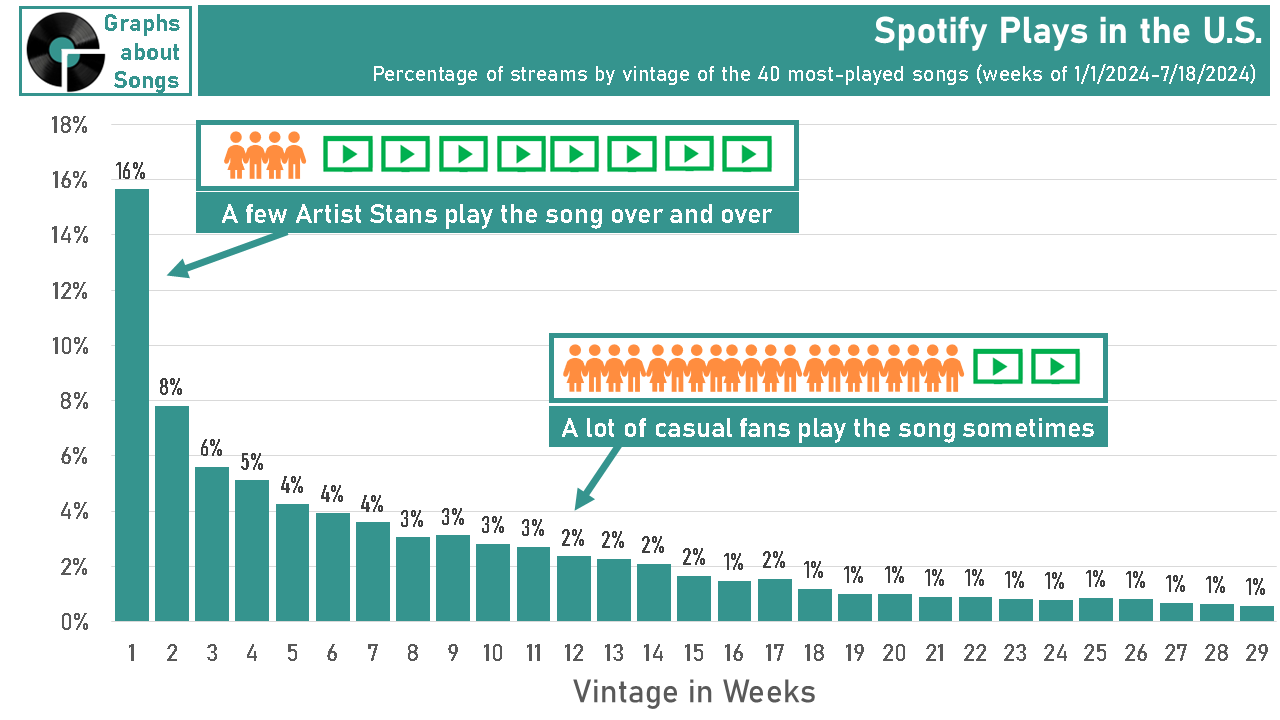

Since the Artist Stan’s consumption is concentrated on the first week when a song drops, however, streaming data amplifies Artist Stan consumption over its Casual Fan consumption on a weekly basis.

Over time, songs that attract Casual Fans will have much higher aggregate streaming counts. During any given week, however, the new release from the big artist has an advantage.

This fact also means Spotify is now replacing both iTunes (and The Record Bar) and your local FM hit music station:

For the first half of the 2010s, paid digital downloads remained dominant over streaming. The explosion of the iTunes store had little impact on the time Americans spent with their favorite local radio stations.

By 2018, however, Spotify rendered iTunes all but irrelevant as the preferred way to hear new music. 2018 also marked a downward trend for the time Americans spent with FM radio. The pandemic in 2020 accelerated that decline, as people stayed out of their cars and more Americans tried streaming.

Billboard doesn’t share the proprietary formula they use to balance physical and digital song sales, audio and video streaming, and terrestrial radio audiences. Based on the growth of Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube, the collapse of iTunes’, and FM radio’s steadily eroding Time Spent Listening (TSL), streaming consumption is now the most significant contributor to the Hot 100’s data.

The result is that 17% of #1 songs don’t stick around long enough to develop a base of Casual Fans—meaning 17% of #1 songs have no lasting impact on our culture.

Streaming has also impacted the charts on the opposite end of longevity---the rise of the Megahit. I define a “Megahit” is a song that remains in the Billboard Hot 100 for longer than 28 weeks.

Before the Streaming Era, only three Top 10 hits became Megahits. Since 2018, 15 songs have stuck around that long, with The Weeknd’s "Blinding Lights" remaining in the Top 10 for a record-setting 57 weeks in 2020-2021

These Megahits are definitely songs folks know and love. Historically, radio stations backed off those huge hits once listeners no longer consider them “in the moment,” which in turn caused those songs to fall out of the Hot 100’s Top 10 once they were six months old at the oldest.

With music consumers increasingly using Spotify to hear the songs of which they’re Causal Fans, there’s no external factor to suddenly limit how often they play those songs. Over time, these songs receive fewer plays each week, but if enough listeners still love it enough, a song can now stay among Spotify’s Top 200 for years.

Is the Hot 100 Now “Wrong”?

Billboard remains true to its mission to measure America’s consumption of songs during the past week, Unfortunately, the Hot 100 is now a less accurate gauge of the songs that the highest percentage of Americans know, love, and are talking about at the moment.

The chart now contains songs that Artist Fans binge when they’re released, but that never attract Casual Fans and—therefore—never become the shared cultural experience we associate with a #1 hit.

The chart now also contains songs that Casual Fans indeed still consume, but have grown too old for even their biggest fans to think of as being “in season” the way we think of #1 hits being the song everyone’s talking about.

Even through the iTunes era, almost every single #1 song remained a top 10 hit long enough for a lots of folks to hear them, but not longer than folks were talking about them. In other words, every #1 song was culturally relevant

Since 2018, however, one-third of #1 songs either vanish from the top 10 before most people have ever hear them, or stick around long after anyone is talking about them. In other words, a third of #1 songs simply aren’t culturally relevant.

That doesn’t mean I think the #1 song inherently doesn’t matter.

As of this writing, the last four #1s were…

Shaboozey ‘s "A Bar Song (Tipsy)", which has bridged Hip Hop and Country in a way that even Beyonce couldn’t quite pull off.

Kendrick Lamar’s "Not Like Us,” which takes his accusations against Drake to a level Hip Hop diss tracks rarely achieve.

Post Malone featuring Morgan Wallen’s "I Had Some Help" teams up Country and Pop’s biggest stars.

"Please Please Please" by Sabrina Carpenter may or may not ultimately have the impact Espresso (#3 peak) has had, but it does confirm that Carpenter is 2024’s biggest breakout Pop artist so far.

If you’ve listened to the radio or been at any Applebees or Target that’s playing current music, you’ve heard these songs.

Granted, Megan Thee Stallion’s "HISS" was also #1 for only one week, then instantly vacated the Top 10. Among Hip Hop fans at least, her diss was the buzz at the time.

(Don’t take my word for why these songs matter: Click on the link on each song to read chart analyst and pop critic Chris Molanphy’s excellent Slate column Why Is This Song No. 1?)

Here’s the rub. Billboard never promised us it was measuring cultural impact:

Billboard is in the business of serving industry professionals with data about music consumption, as are Luminate, Mediabase, and Nielsen Audio, whose data creates the Hot 100. While we can—and will endlessly—debate which data matters most, it’s still data.

Cultural impact is subjective.

When Oldies fans discuss The Beatles’ 1964 chart feats, or Thriller’s 1983 string of singles, we’re really recalling the impact that music had on our times.

We once measured a song’s popularity in sheet music sales, player piano rolls, and Jukebox plays. In time, we will also adjust our benchmarks for a music industry where paid digital downloads and FM radio spins are relics of yesteryear.

Sources for this post:

The Billboard Hot 100: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100

Wikipedia’s Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 singles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles

Further reading:

Slate: Why Is This Song No. 1? by Chris Molanphy: https://slate.com/tag/why-is-this-songno1

Stereogum: The Number Ones: by Tom Breihan: https://www.stereogum.com/category/the-number-ones/

Terrific deep dive into #1's. Granted, my music consumption is still from physical LP/CD's and iTunes, but I would say I fall into both categories of fans. As a mentor of 16-21 year old foster youth (men), I am shocked at how many of them dislike THIER generation's music. Since I don't stream, I will share my thoughts on two topics...that I believe can still be saved...and make following the charts fun again.

1. iTunes: As a long-time customer of iTunes, I would suggest they invest a little more time identifying all new music. In addition, create a category for classic (or) AC artists. (It takes time to find Olivia's new duets albums, Melissa Manchester's new retakes on her songs, or even single releases by Christopher Cross.) Other thoughts would be sequencing songs/LP's by release date, including that release year (for all artists), and even removing older songs from current charts...did the constant ranking of "Don't Stop Believin" keep me from discovering new music on their best seller list. I would add...color code the songs so if I see a new album by an artist I like, somehow, let me know the first single release so I know what the artist/record company is promoting.

2. Billboard. Before I could afford it, I subscribed to Billboard starting in the early 1980's (and still have them...but about to end that hoarding habit.) I went from reading it the day I received my copy to now having several copies untouched. (They want you to go their website...and see the charts with many obnoxious pop-ups.) While I understand it's an "industry" paper, in my opinion, the writers are not fans (or aware) of the history (and importance) of Billboard. I see too many articles about Hollywood stars (that don't sing), politics (legislation is fine...don't care which artist held a fundraiser), and constant rankings of their writers favorite albums, songs, etc. The number of articles about "Texas Hold'em" was silly. I've shared my recommendations with Billboard...although I would add one more, add Mr. Bailey to their team.

Thanks again. Any day with a new "Graphs about Songs" article is a good one!

Good and interesting article relative to the "good data" era of Billboard. I mine the prehistoric era where there was no numeric data--just the charts--and there are analogies.

First, as the article points out, economics does not matter in the choice of music today. In the '60s, investing 98 cents was a big deal and required choices. Don't get me started on the angst of $3.98 for a mono album. Second, I would argue that we've overplayed the significance of simply being a number 1 record for decades. For at least the pre-Soundscan era if not today, more records peaked at number 1 than at any other rank and it doesn't matter what magazine or what genre. In some years, such as 1974 (including "Whatever Gets You Through The Night") there were 35 number 1s out of 495 chart entries--over 7% and nearly a new one every week. On the other hand, some years (1971: 18 of 615, 2.9%; 1978: 19 of 449, 4.2%) there were relatively fewer. The difference is average duration at number 1 (and all peaks, for that matter) and outlier durations of 6 weeks in 1971 or 10 weeks in 1978. In short, there are times when there is consensus about records and times when it's a search for the next shiny object. Using the terminology of the current article, when there is consensus, the Stans and Casual fans agree. When there is none, the spiky influence of the Stans shows alongside the indifference of the Casuals. Usually times of consensus are times when there is agreement on a dominant genre--at the other times there is none, or dominant genres are changing. Velocity going up and going down is relatively similar over time (modulated a bit by total chart entries). Time at peak is the real determinant.

Refs: Some Years are Just Better than Others.

The Importance of Public Consensus in Record Ranking, Rock Music Studies, DOI: 10.1080/19401159.2023.2184914

Not So Lonely at the Top: Billboard #1s and a New

Methodology for Comparing Records, 1958–75, Popular Music and Society, 38:5, 586-610, DOI:

10.1080/03007766.2014.991188