Billboard Has Had Enough of Your Teddy Swims

The Hot 100 Songs Chart has sweeping new rules that kick out older songs. You’d reasonably assume Streaming inspired this change. This time, you'd be wrong.

Like you, the folks at Billboard are tired of seeing songs on their Hot 100 chart that have been around for months, or—in two cases—years.

So, starting with the chart for the week ending October 25th, 2025, Billboard has created a new policy that removes songs from the Hot 100 simply because they’re too damn old. Here are the four situations when Billboard will now drop a song:

If a song falls below #5 and has been on the Hot 100 for 78 weeks

If a song falls below #10 and has been on the Hot 100 for 52 weeks

If a song falls below #25 and has been on the Hot 100 for 26 weeks

If a song falls below #50 and has been on the Hot 100 for 20 weeks

Billboard already kicked out songs that fell below #50 after 20 weeks, a policy in place since 1992. They also implemented a policy in 2015 for songs falling below #25, but the new rule tightens that time frame from 52 weeks on the chart to only 26 weeks. The two new rules impacting songs that fall out of the top 5 or the top 10, however, are unprecedented in Hot 100 history.

Thanks to the new policy, you suddenly won’t find these songs on the Hot 100:

· Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” (119 weeks on the Hot 100)

· Benson Boone’s “Beautiful Things” (89 weeks on the Hot 100)

· Lady Gaga and Bruno Mars’ “Die With a Smile” (60 weeks on the Hot 100)

Morgan Wallen’s “I’m the Problem” and “Just in Case,” “Sorry I’m Here for Someone Else“ by Benson Boone, “Luther“ by Kendrick Lamar featuring SZA, and sombr’s “undressed” are also now gone from the Hot 100 after a lengthy stay.

The rule to knock out songs that fall out of the top 5 (but are still in the top 10) after 78 weeks seems specifically targeted at Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control.” As late as early October, “Lose Control” was still #6. (It only fell out of the Top 10 because the 12 tracks from Taylor Swift’s The Life Of A Showgirl took over #1 through #12).

Without this rule, “Lose Control” would likely re-enter the Top 10 once Swifties are done binging her latest album.

Instead, “Lose Control’s” chart history is finally locked at 119 weeks in the Hot 100 and 80 total weeks in the Top 10, a record that will likely go unbroken under the new rules.

Why the Hot 100 exists

Most folks simply think the Billboard Hot 100 ranks America’s most popular songs. If you’re of a certain age, you’ll instantly recall Casey Kasem counting it down during the 1970s and 1980s heyday of American Top 40.

Today, having the #1 song in the U.S.A. remains a crowning achievement—and the Hot 100 is the authoritative chart that coronates it. Billboard, however, doesn’t care what you think of their chart… unless you work for a record label.

The charts Billboard Magazine compiles are tools for music industry professionals to understand how their songs and artists perform in the marketplace, so they can allocate resources accordingly.

The Hot 100 doesn’t rank popularity per se, either: Instead, it measures which songs Americans consume most, regardless of their genre and regardless of how fans consume them, to provide an overall leader board of popular music.

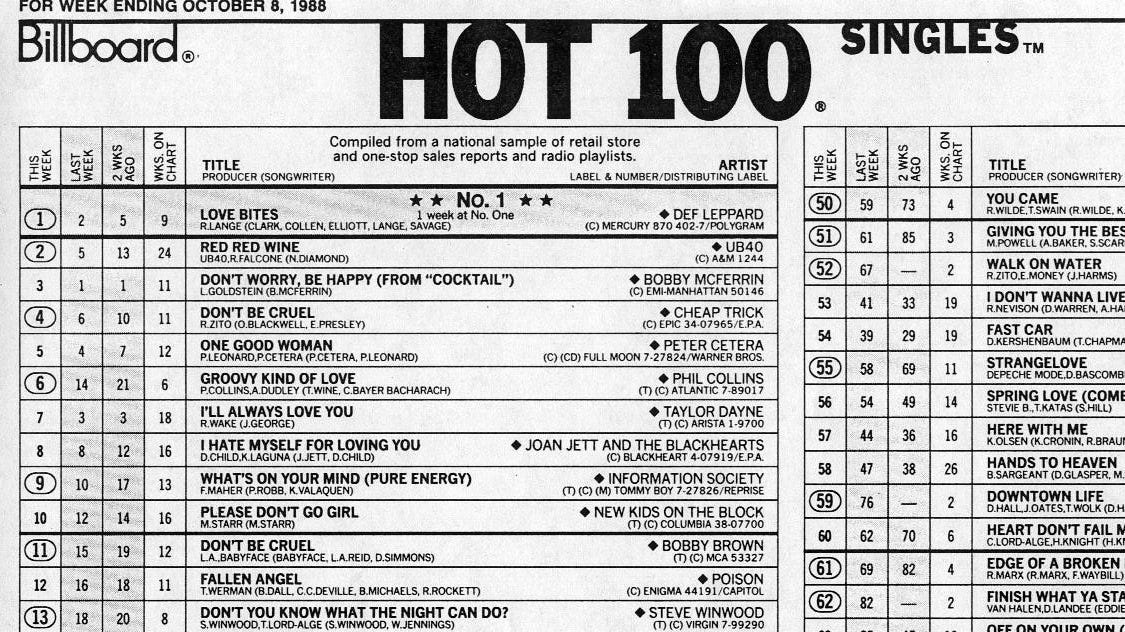

Historically, the Hot 100 combined data on how many fans bought a song (first on 45-RPM records, Cassette Singles, or CD Singles), along with how often terrestrial radio stations played the song. That meant the Hot 100 captured both active consumption of a song (for those who rushed out to Sam Goody to buy it) and passive consumption (when you merely enjoyed it on Kiss-FM)

In 2005, Billboard added paid digital downloads of individual songs on services such as iTunes to their calculations. In 2007, Billboard augmented their radio data with a limited number of internet radio services, chiefly AOL Music and Yahoo! Music.

The biggest change, however, came in 2012 when Billboard also added on-demand music streaming from services such as Spotify, followed by video streams in 2013, primarily from YouTube. (Ironically for us Xers, even in the halcyon days of MTV, the chart never included music video airplay.) At that time, iTunes purchases and FM radio still dominated music consumption.

Today, the Hot 100 is still a three-pronged gauge measuring song sales, airplay, and streaming. By the early 2020s, however, Spotify and its on-demand clones have surpassed radio and almost completely usurped sales as the metric that matters most.

It’s streaming, right?

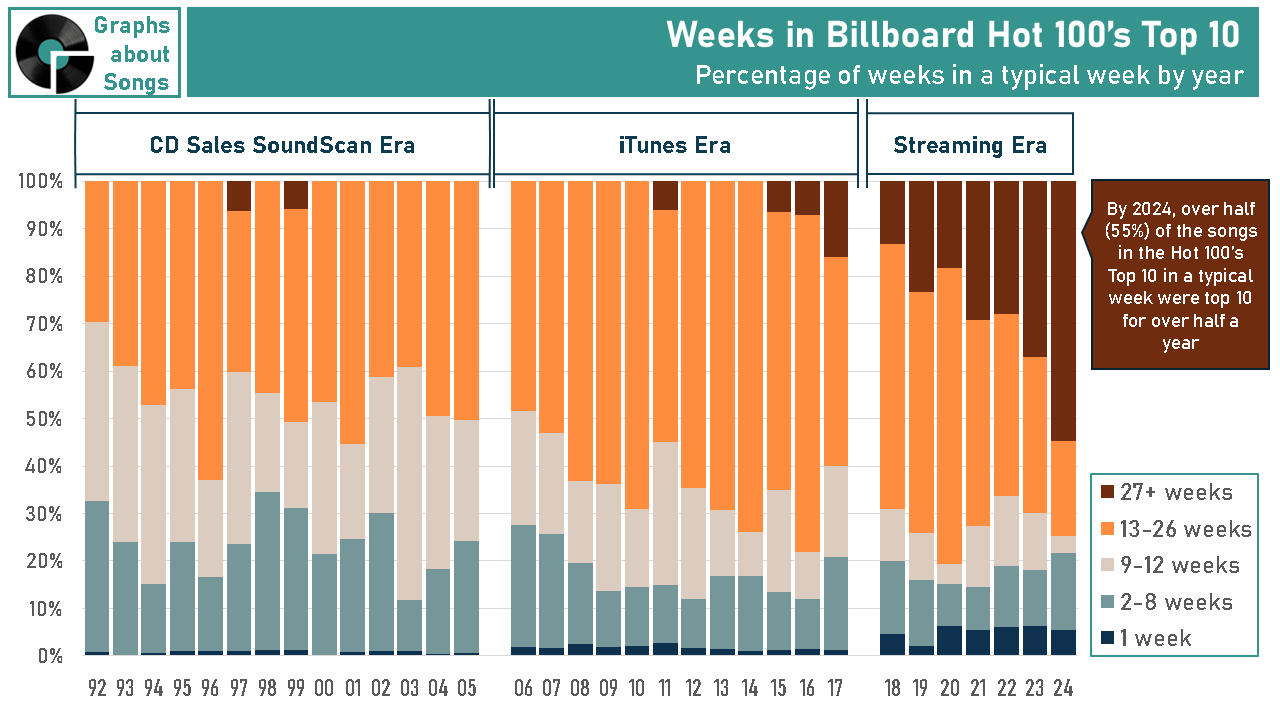

Unquestionably, streaming has kept songs charting for much longer than songs did back when we bought our tunes. Examine the graph below, showing how many weeks the typical Top 10 hit in a typical week stays in the Top 10:

In 2015, hardly any songs in the Top 10 were over half a year old.

By 2024, over half (55%)) of the songs in the Top 10 in a typical week would stay Top 10 for over half a year.

That’s the exact time frame when Spotify replaced iTunes.

As I detailed in Do You Have To Let It Linger, the reason is fundamental:

When we bought music, we only registered your fandom when Circuit City or Apple ran your credit card. We had no idea how often you played a song after you bought it.

With streaming, however, we measure every single time you play a song. That means we know which songs fans keep playing week after week—or year after year—compared to the songs folks quickly abandon.

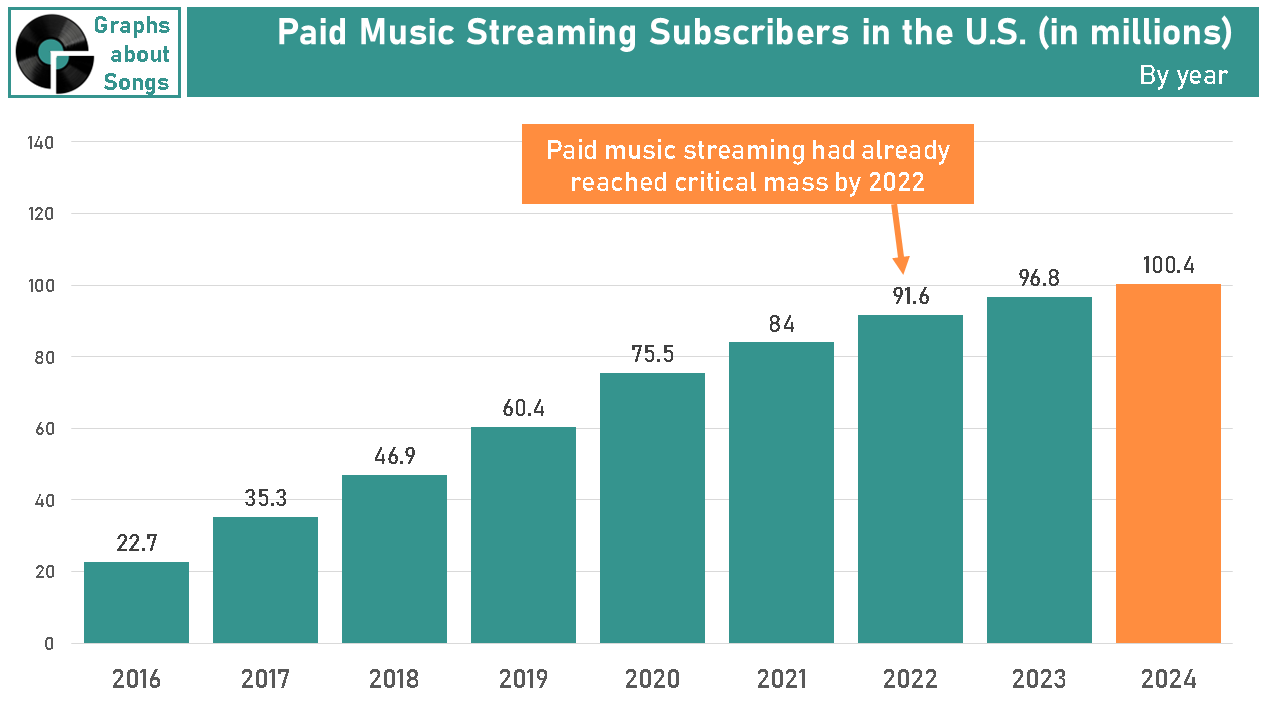

Before we blame Spotify subscribers for playing Teddy Swims until it hurts, take a closer look at that chart: As late as 2022, only 28% of the Top 10 songs in a typical week or 27 weeks old or older. At that point, we ‘d already reached mass-adoption of streaming:

Paid music streaming subscriptions only grew an additional 9% from 2022 to 2024. During those same two years, the percentage of songs that lingered in the Top 10 for over half a year almost doubled from 28% to 55%.

So we can’t blame the recent rash of Hot 100 stagnation exclusively on increased streaming adoption.

“Okay, but are people streaming the same old songs for longer than they used to?”

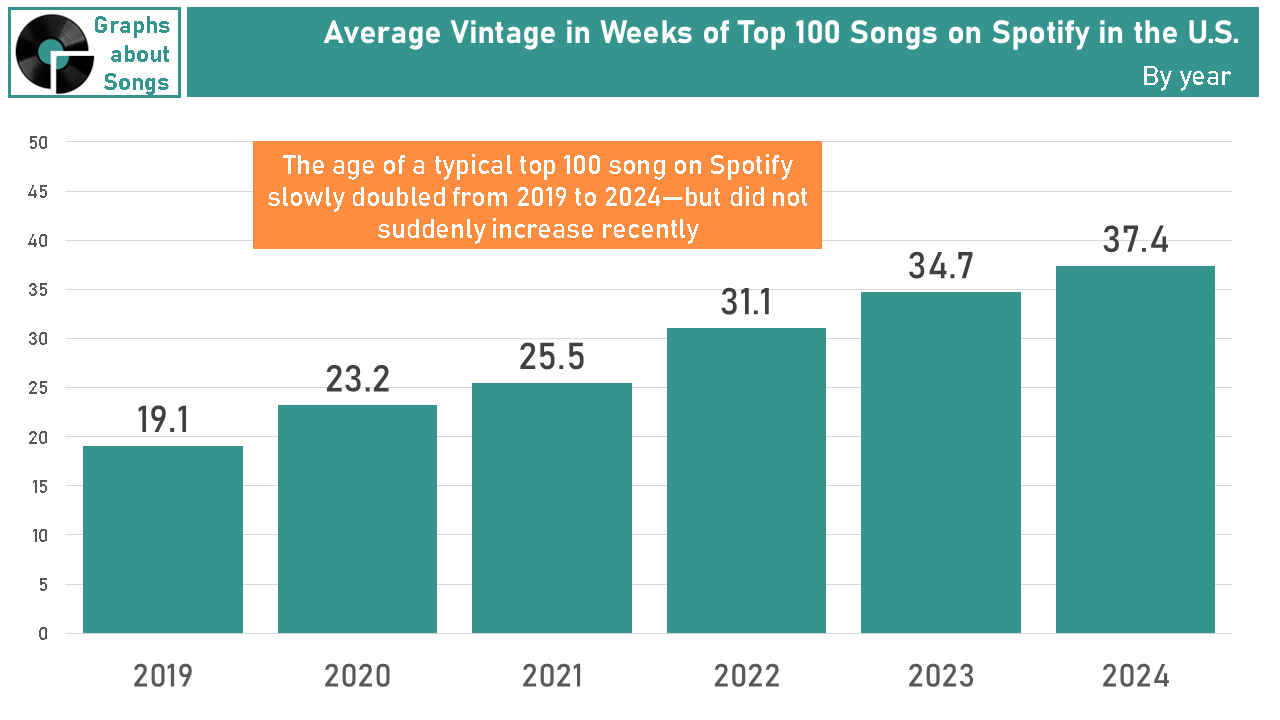

Among Spotify’s top 100 songs each week, the typical vintage has almost doubled since 2019. (I suspect that’s primarily because the average age of a Spotify listener has increased as older adults have adopted streaming. The older you get, the slower you typically become aware of new music.) As with music streaming subscriptions, however, that increase has been slow and steady, not sudden in the last two years.

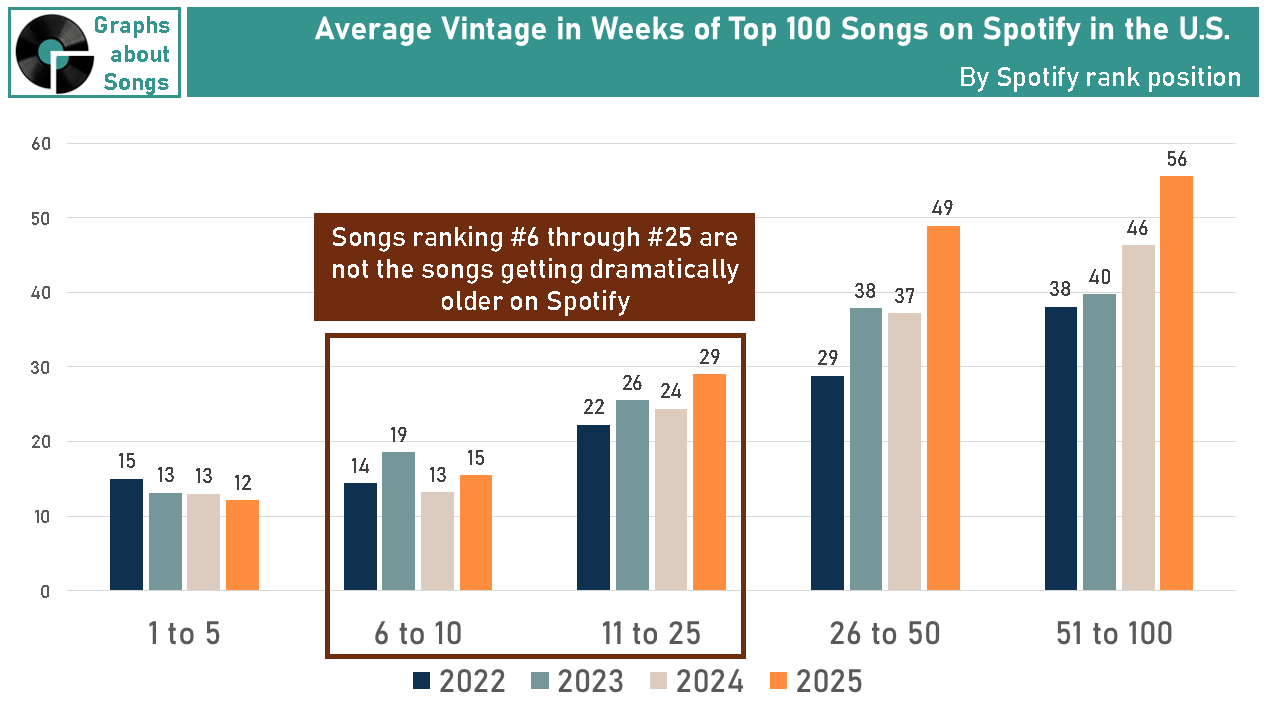

Let’s break it down further and examine the average vintage of a song based on how it ranks on Spotify. If Billboard’s Hot 100 rule change is due to streaming, we should see songs that rank #6 through #25—the songs targeted by the updated policy—become a lot older since 2022.

We do see growth in older songs lingering among Spotify’s Top 100—but those aging hits are generally ranked #26 or lower, not the Top 25 songs Billboard is forcing out under its updated policy.

So if streaming alone can’t explain the sudden surge in old songs hanging out near the top of the Hot 100, what is?

Go back and take another look at the specific songs Billboard’s new rule removes from the Hot 100. They’re all songs you’ll hear on your local radio stations today—probably several times today. That’s no coincidence.

Why radio—not streaming—has forced Billboard’s hand

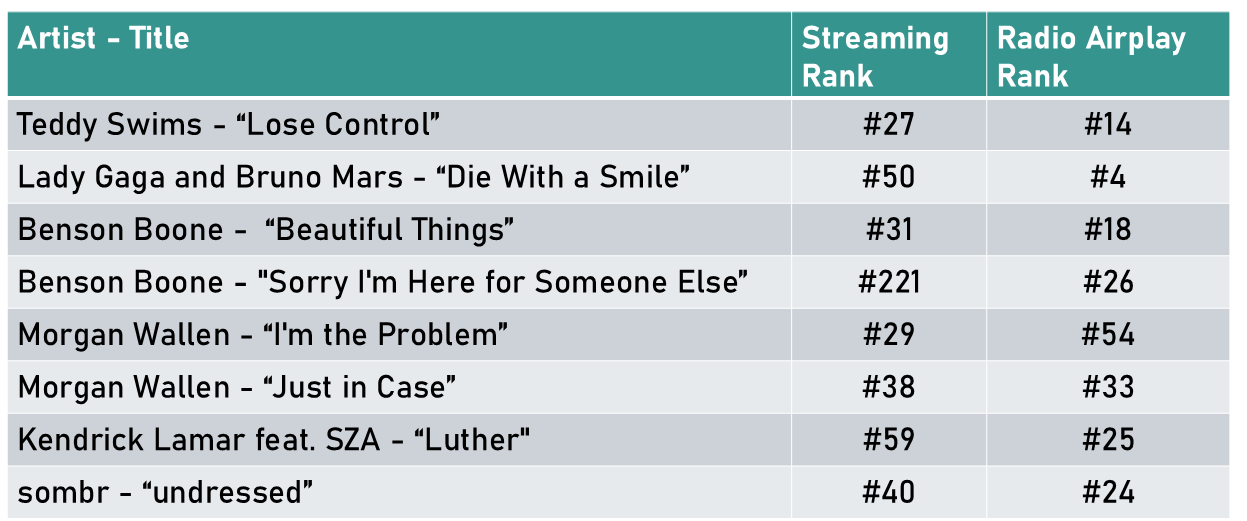

Let’s revisit the specific eight songs the new Hot 100 policy kicked off the chart. The chart below shows how each song ranked in total on-demand audio streaming in the U.S. vs. its radio airplay audience for the week ending October 9th, 2025:

While all of these songs rank much higher in airplay than in streaming, that’s not a fair comparison. Between Taylor Swift’s The Life of A Showgirl and the K-Pop Demon Hunters Soundtrack, there are 17 album cuts that fans are currently streaming en masse that simply aren’t relevant to radio.

Let’s make a fair comparison.

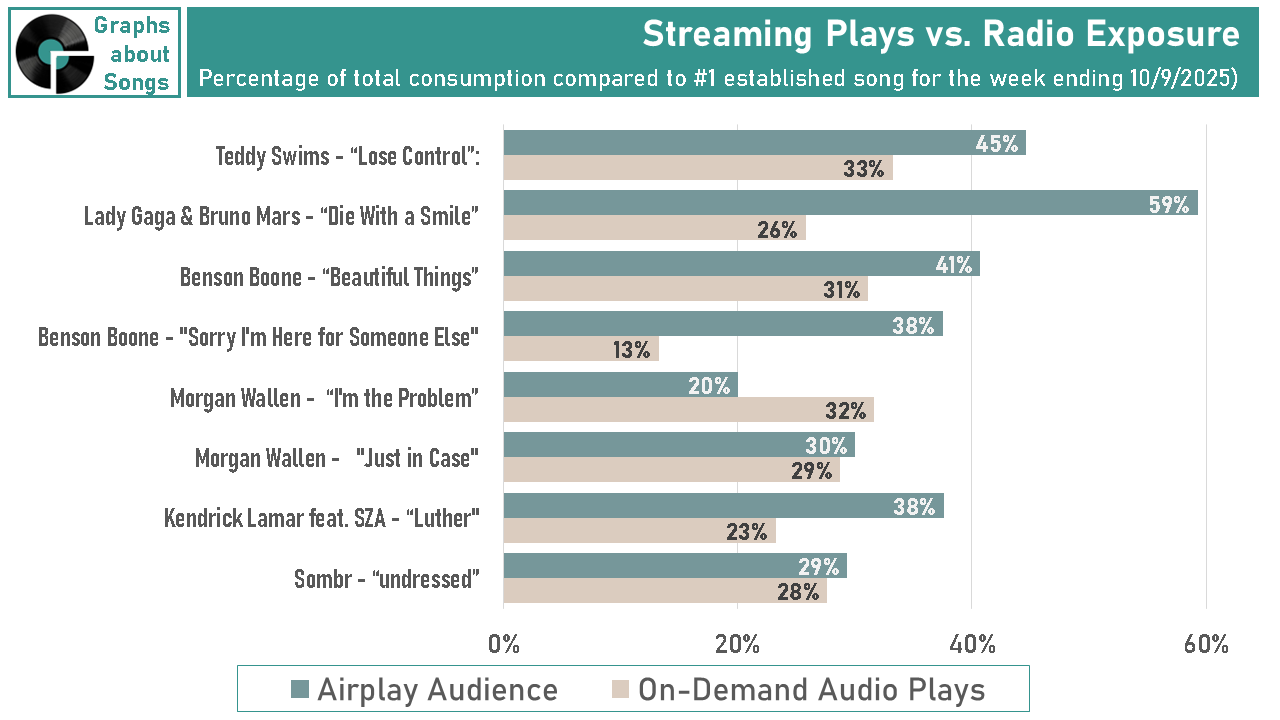

The graph below shows the percentage of the songs’ streaming vs. radio exposure compared to the #1 established* song in streaming and #1 song in airplay.

*Established??? The #1 most-streamed song was Taylor Swift’s The Fate of Ophelia, which since it only recently dropped, is still receiving inordinately large play counts thanks to Swift’s most ardent fans playing her new album incessantly. To create a fair comparison, I instead used the most-streamed song that had been out for at least eight weeks, which is the typical time frame radio’s casual listeners take to get to know and like a new song. Coincidentally, that only removes the new Swift songs from our comparison.

Our “established #1 song on streaming “Golden” from the K-Pop Demon Hunters soundtrack.

Meanwhile, the #1 comparison track for radio is Alex Warren’s Ordinary.

The way to read this graph is that fans streamed “Lose Control” 33% as often as they streamed the #1 biggest song (“Golden”), while radio listeners heard “Lose Control” 45% as frequently as they heard the #1 most played song on the radio (“Ordinary).

For all eight songs except one, you will notice a trend. The song’s radio airplay is contributing more to its chart performance than its streaming.

That means radio contributed more to those songs’ lingering chart presence than did streaming.

Why Is radio changing the Hot 100 now?

Given the purpose of Billboard’s music charts,, it makes business sense why they want old songs off the chart. Labels want data about which up-and-coming songs will benefit most from their promotional investment. Knowing that “Lose Control” and I’m The Problem” are still big doesn’t tell them anything helpful.

The real question is why are FM radio stations—including stations that focus on Today’s Hit Music—-holding on to hit songs longer than ever before? We’ll dive into that topic in an upcoming post.

Also worth a read:

NPR: “After months of the same songs on the Hot 100, ‘Billboard’ tweaks its rules”: https://www.npr.org/2025/10/22/g-s1-94489/billboard-hot-100-chart-changes-songs

Data sources for this post:

The Billboard Hot 100: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100

Wikipedia’s Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 singles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles

Spotify 200, United States, weeks ending January 3rd, 2019 through October 9th, 2025: https://charts.spotify.com/charts/overview/us

Additional data provided by Luminte and Mediabase.