Are There Really Fewer Real Hits Today?

There’s a technology to blame here—and it’s not streaming.

Turn on your local hit music station right now. There’s a good chance you’ll hear a song that’s several years old. You might have to wait through a few old standbys before you actually hear a “current” hit.

That station’s program director will tell you there just aren’t enough good new songs to choose from to play “today’s” hit music. Most folks would rather hear Post Malone’s “Circles” yet again than most of the songs released recently.

Is this widely held belief based on verifiable data—such as audience research or streaming consumption—or is it based on opinion and personal musical preferences? Is there an empirical, medium-agnostic metric we can examine that will show clearly if there really are fewer “real” hits today than in the past?

That’s what I’m here to do.

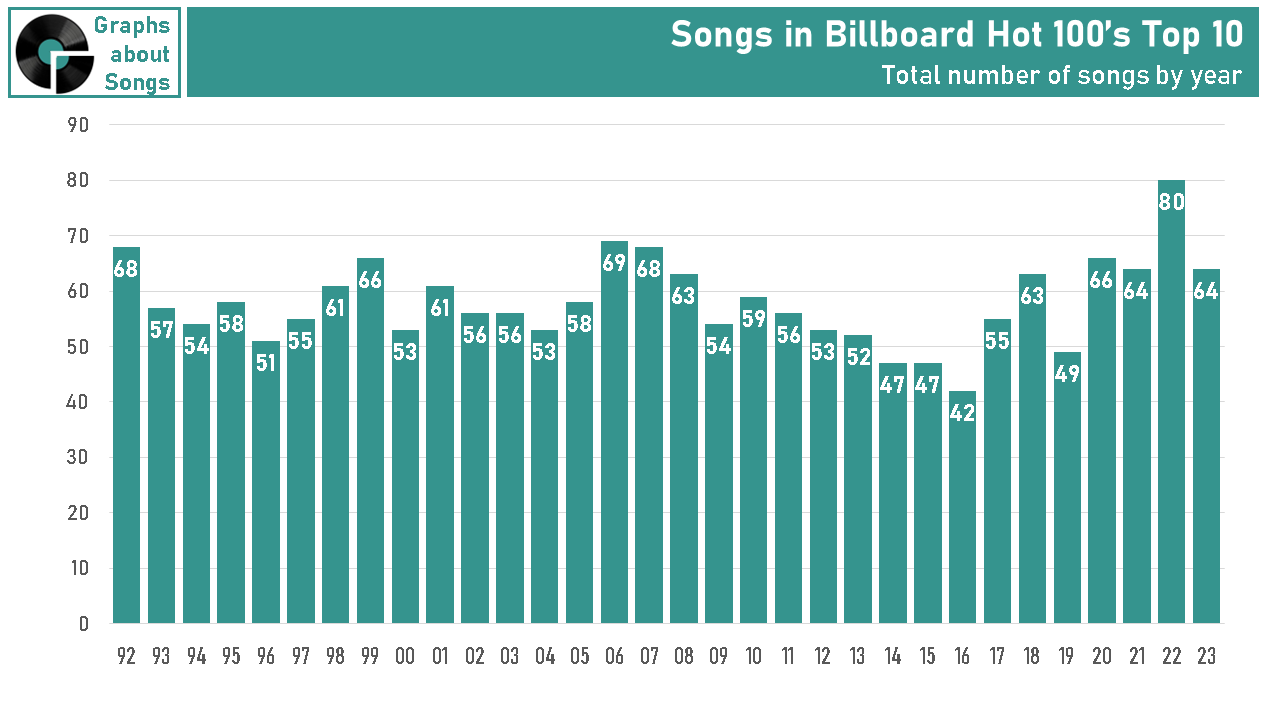

Let’s examine, as we have in several other posts, the songs that made the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 over time. As a multi-media, all-genre chart, the Hot 100 gives us a balanced look at the songs Americans consumed most throughout the years, regardless of whether they bought them on 45, streamed them on Spotify, or heard them on the radio.

For this exercise, we’ll start in 1992, after Billboard transitioned from self-reported sales and airplay data to electronic monitoring of these metrics.

If we simply examine how many Top 10 hits there are each year, 2023 looks as good as any year.

That metric, however, is useless.

As I explained in detail, streaming has given rise to “one and done” songs that only make the top 10 the week they’re released when the artist’s fans binge them, and then tumble off the charts. Before streaming, we couldn’t measure how many times someone played a song, so binge listening wasn’t a thing. These songs never become favorites of a wider audience that make a song a shared cultural experience. (Sometimes, even the artist’s core fans decide they don’t like them.)

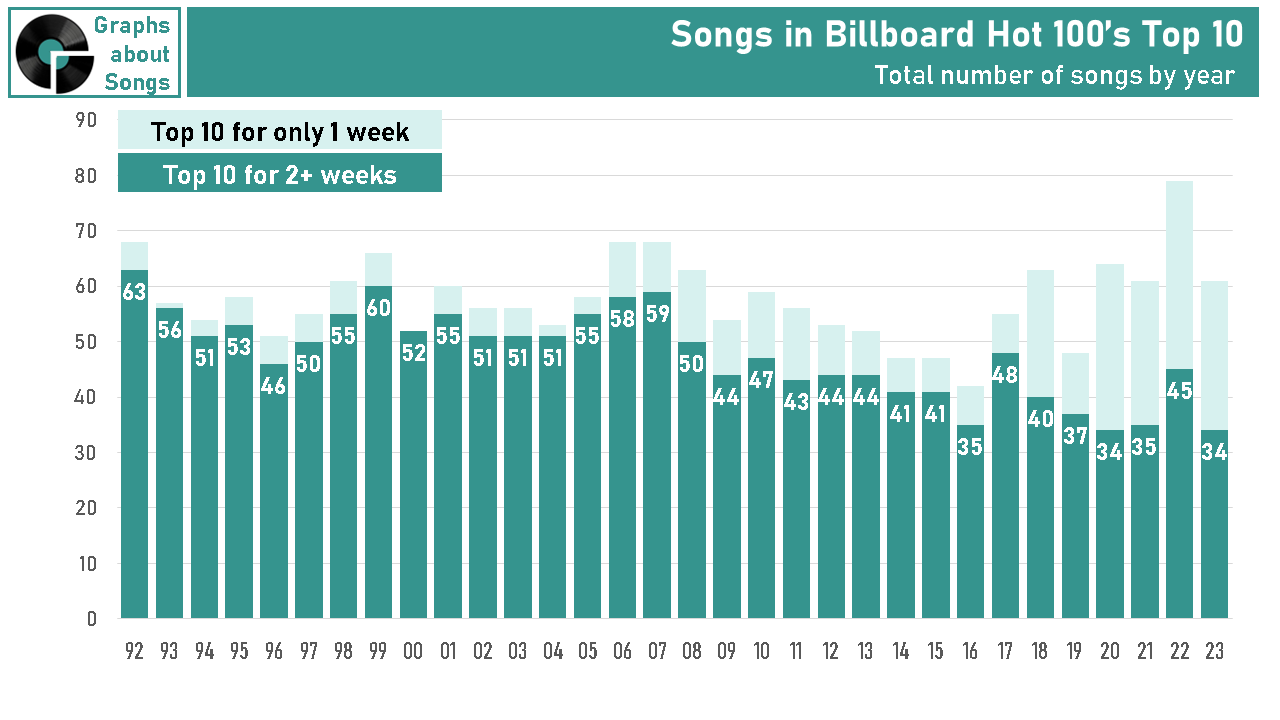

So first, let’s remove those songs that only remain in the Top 10 for one week.

You might already spot a trend here, but let’s take it one step further: Let’s remove those songs that only stick around the top 10 for only two to three weeks and zone in on songs that stay in the top 10 for at least four weeks. (I admit four weeks is an arbitrary time frame for deciding a song is really a hit. However, examining songs that remain in the top 10 for five, six, or even eight weeks yields comparable findings.)

What does this analysis reveal?

There were only 21 songs that were top 10 hits in 2023 for at least four weeks, That’s fewer than half as many songs as met that “real” hit metric throughout the 1990s and most of the 2000s. As late as 2007, 45 songs were top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 for at least four weeks. That number steadily fell in subsequent years. By 2019, only 31 songs qualified.

What’s causing this paucity?

Is it streaming? Those one week only top 10 songs do push songs with real staying power out of the top 10 in any given week. (By definition, there are only ten top 10 songs each week.) However, the trend of fewer songs achieving the four-week benchmark started a full decade before streaming eclipsed iTunes in the late 2010s. So we can’t simply blame streaming.

Is it over-researched radio? Some claim callout research—radio’s primary tool for gauging which songs listeners know and love most—has ruined radio by preventing any song that doesn’t ‘test” from making the playlist. However, callout has been a thing since the 1970s. Savvy programmers have long understood it isn’t a tool to judge brand new songs listeners haven’t yet heard often.

Is it inherently crappy music? There are certain points in popular music history that critics widely believe to have sucked: The early ‘60s after Elvis but before the Beatles. The early ‘80s after Disco but before New Wave. However, these years don’t have significantly fewer songs making the top 10 for four or more weeks than do the widely beloved pop music renaissances that followed them.

There is one overlooked technology that I theorize has caused us to have fewer real hits year after year.

The Portable People Meter (PPM)

Starting in 2007, the U.S. radio industry transitioned from measuring audiences with paper diaries, where listeners (imprecisely) wrote down which stations they heard, to passively tracking listening using a device that looks like a beeper. This Portable People Meter detects inaudible tones in radio broadcasts to determine which stations are playing in your presence, without you having to remember to write it down or even know which station you’re hearing.

Since this new tool measured radio listening on a minute-by-minute basis, PPM also spawned MScore, which shows correlations between songs and tune outs.

MScore was brutal to new music.

As soon as it launched, Mscore showed that playing a new and unfamiliar song correlated to a drop in listenership of up to 40 percent.

Radio stations responded to Mscore’s newfound insight by downplaying new songs.

Instead of your favorite disk jockey hyping a hot new release, their bosses told them not to mention new songs. Radio still played new songs, but buried them silently between established hits or right after a long commercial break, hoping listeners wouldn’t notice them.

Unfortunately, radio got exactly what it wanted: Listeners stopped perceiving radio as the place they discovered new songs. As Spotify and YouTube became mainstream services in the late 2010s, music fans increasingly perceived these services as the place to fall in love with new music.

Conversely, Mscore also showed that the songs least likely to correlate to tune out were widely familiar songs that were often several years old. This discovery flew in the face of programmers’ long-held understanding that listeners eventually grow weary of current songs once they’re no longer current and playing those worn out songs causes tune out. For decades, stations asked listeners if they were tired of hearing a song in callout research and would back off playing it once this “burn” score grew too high.

But PPM and Mscore said those three-year-old favorites kept listeners tuned in, so more and more stations kept those older songs in heavy rotation.

It all made perfect sense. If new songs cause tune out and old songs keep folks tuned in, play last year’s favorites and you’ll have the biggest audience in town.

There’s just one problem.

Even if Mscore correctly highlights what causes people to tune out, it reveals absolutely nothing about why they tuned in to the station in the first place. For listeners who choose a contemporary formatted station, keeping in touch with today’s music trends is a big reason they tune in.

By downplaying new music and keeping older hits in heavy rotation, those listeners found less incentive to tune in with each passing year, as they could no longer count on thier hit music station to keep them up to date with the hits.

Perhaps that’s why America’s biggest hit music stations have lost 51 percent of their weekly listeners over the last ten years. That decline was underway before Spotify and Apple CarPlay became commonplace,, so we can’t simply blame streaming here.

But despite the decline in listening and contrary to radio’s naysayers, radio remains the most likely medium to help a song become popular with a mass audience. A song can’t become a huge hit solely from an artist’s fans seeking it out. Even Taylor Swift isn’t that almighty. To become a real hit, the song has to become well-known and well-liked by a whole lot of people who never intended to hear it.

In other words, someone else has to play it for them.

There’s still no medium that reaches more people when it plays a new song for other people than radio.

(In a future post, I’ll spotlight several songs where radio airplay clearly increased Spotify streaming.)

Here’s the rub.

That person who heard Tate McRae’s “Greedy” a dozen times on her local Top 40 station before ever adding it to her workout playlist thinks she discovered it on Spotify. Why? Because she never heard her local top 40 station promote it as new when they played it. She has no perception of discovering it on the radio.

To sum up my hot take here: There are so few real hits today in part because radio isn’t playing and promoting new songs enough to help them become real hits. PPM is largely to blame for that misstep.

It’s time for radio to re-embrace its hit-making role while it still has the reach to reclaim it.

Sources for this post:

The Billboard Hot 100: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100

Wikipedia’s Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 singles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles

Where Did All Those P4s And P5s Go? by Fred Jacobs · November 8, 2023: https://jacobsmedia.com/where-did-all-those-p4s-and-p5s-go/

I don’t disagree with you at all. But, here are some of my quick thoughts: radio often plays it safe (I’m guilty here!!) by watching other sources for guaranteed hits

It came down (to me) as a station perhaps 1) lacking budget for its own research and/or 2) not wanting to RISK anything on new music. In other words: play it safe by playing the KNOWN/familiar hits and if we can’t afford to poll our own audience…then look at soundscan, YouTube, Spotify, iTunes, the other stations we know are paying for research, etc.

Now, about risk: maybe it would be easier to risk if the station was the 3rd, 4th, 5th station in town playing the same music. The risk there may be an easier pill to swallow because you want to stand out by being the place for new music.

Matt, Thank you for another great article! This is both timely and thought provoking. Keep up the great work you're doing, it's incredibly helpful and needed.