Once Upon a Time when Radio Played New Music

The "new" songs you're likely to hear on the radio today are well known, widely loved, and proven hits in research. And it's accelerating radio's audience erosion.

I’ve heard it repeatedly from radio professionals who also are the parents of teenagers:

The local Top 40 station—perhaps the one you program—proclaims, “here’s the new song from…”

Your teen bemoans, “that song’s been out for months.”

Your teenager’s observation isn’t hyperbole.

Radio’s “hit” songs

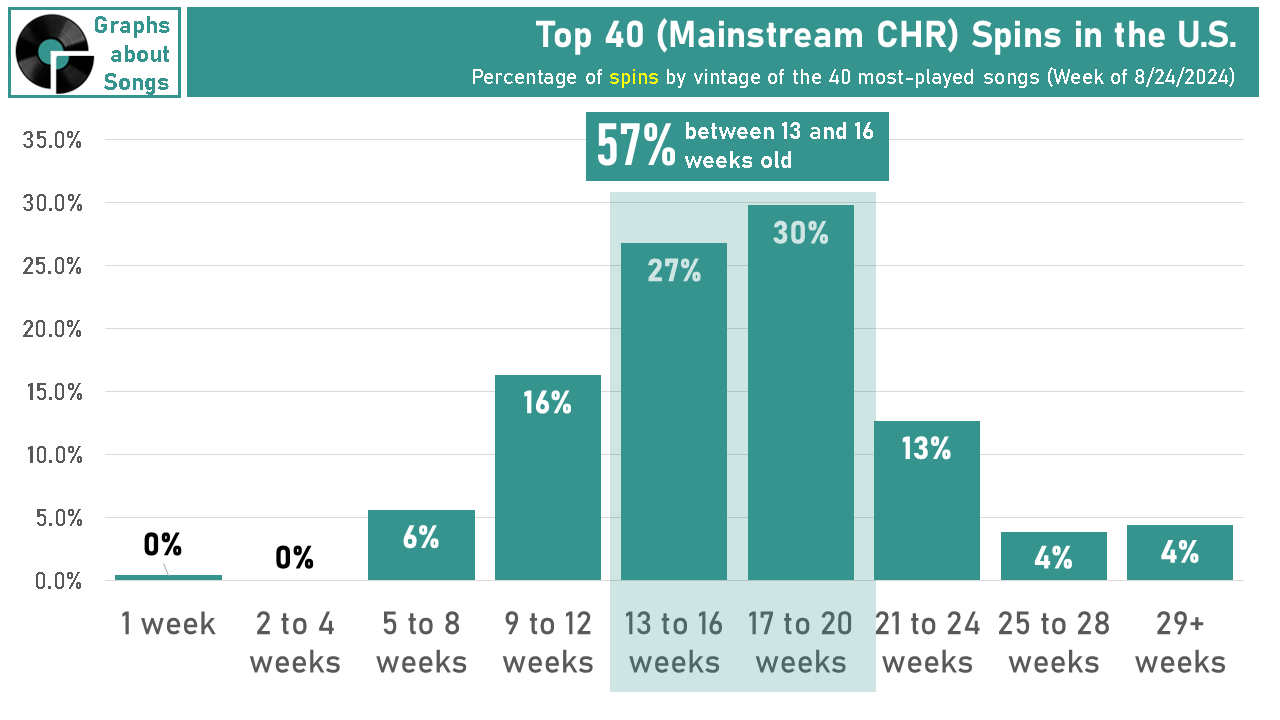

Here’s the vintage of current songs played on America’s Mainstream Top 40 Radio stations—the stations that bill themselves as “the hit music station”—last week. (I’m basing the vintage here based on the first week each song appeared in Spotify’s Top 200). Note that only one in five songs are eight weeks old or newer:

Even when your local Top 40 station plays a song that’s less than two months old, they tend to play that song far less often than they play established hits. Here’s the same song vintage graph, but based on how many times Top 40 stations played songs:

Compared side by side, only 6% of the “current” songs you’ll typically hear on your local hit music station are eight weeks old or newer. If we assume the typical station plays eight “current” and four older songs an hour, you’d have to wait over two hours to hear a song that’s less than two months old.

Spotify’s hit songs

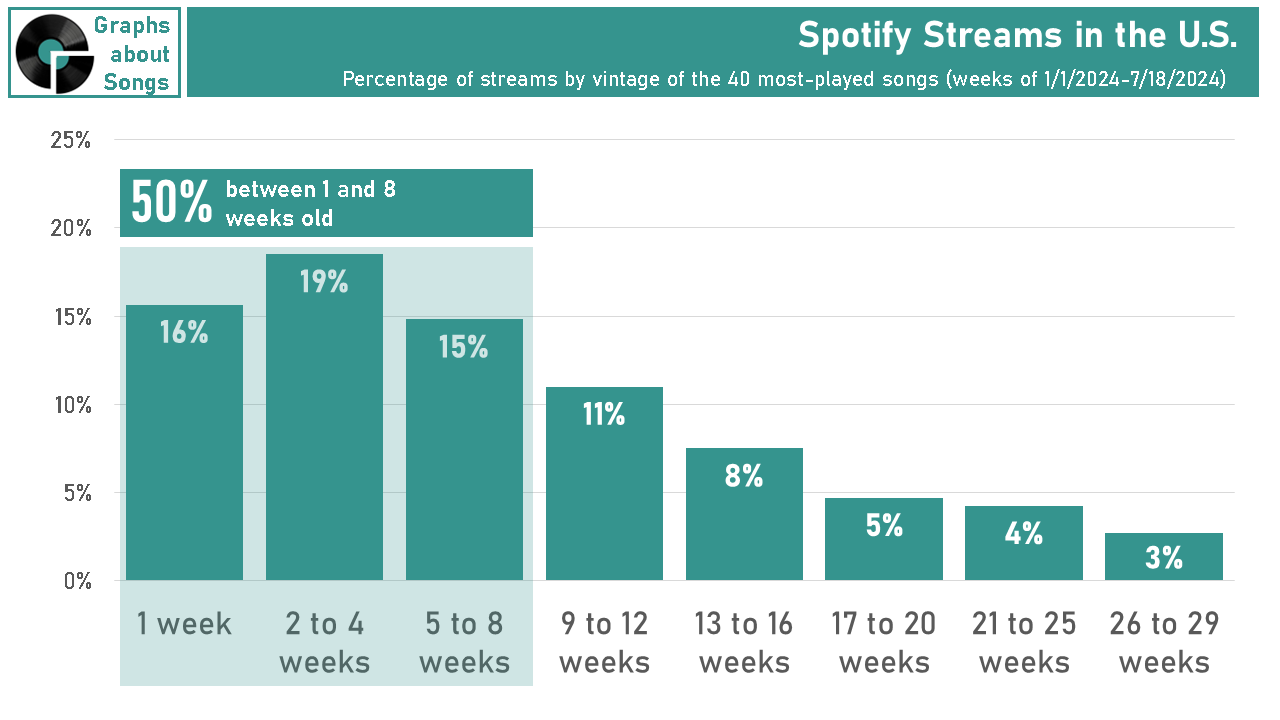

Here’s the vintage of the Top 40 songs on Spotify during a typical week:

As you’ll clearly note below, the vintage of songs that comprise the majority of the songs listeners are playing on Spotify comprise only 6% of the songs you’ll hear on your local hit music station. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the songs listeners hear on Top 40 radio only comprise one-fourth of the Top 40 songs people play for themselves on Spotify.

So yes—if your Gen Z know it all heard the song when it debuted on Spotify, she’s likely accurately reporting that she already has heard that song for months when her local FM station is playing it most frequently.

It wasn’t always this way.

There was a time when radio played brand new songs and did so boldly. However, two discoveries about how people consume music inadvertently killed radio’s commitment to exposing new music.

As Hip Hop’s greatest disser recently said, “bear with me for a second, let me put y'all on game.”

Once Upon A Time…

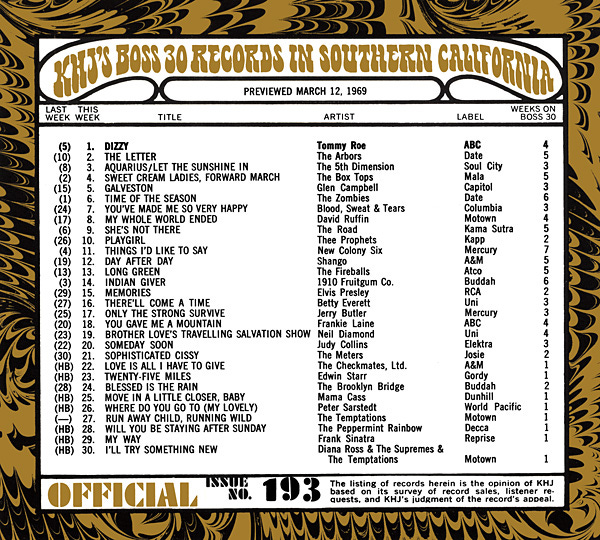

If you saw Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, you heard 93/KHJ. When it launched in 1965, KHJ trounced two established Top 40s and became L.A.’s ratings-dominant station in just three months. Quentin Tarantino reportedly binged 14 hours of KHJ recordings from 1969 to develop the film’s soundtrack. KHJ’s famous Boss Jocks The Real Don Steele and Charlie Tuna, along with the iconic “93-KHJ” jingle, are pretty much characters in the film.

In 1969, radio programmers primarily picked music by record sales: Whatever 45-RPM singles folks were buying, that’s what they were playing. When people stopped buying a song, radio stopped playing it.

93/KHJ had a music system so simple, it would give today’s programmers cardiac events: Bill Drake and Ron Jacobs identified the 30 best currents, including brand new songs they thought were “Hitbound”. Jocks picked 10 songs each hour from the list, playing all 30 once during their three-hour shift. The “Boss Jocks” picked which songs they played during each three-hour show using the same “KHJ Boss 30” Survey teenagers collected from SoCal record stores.

The effect is that every current—from the year’s biggest hit to this week’s brand-new releases—got 56 spins a week on KHJ. That’s a lot less often than today’s stations play the biggest hits, but a lot more frequently than they play new and growing songs.

And how old were those songs?

Meanwhile on the other coast…

Musicradio 77 WABC is as legendary as 93/KHJ, but as different as New York is from L.A. WABC also based their song selections on local record sales. (They even developed a system to randomly survey local record retailers so record labels wouldn’t know which stores they were polling that week and couldn’t bribe them to report fake sales.)

However, their programmer Rick Sklar was far more conservative regarding which songs made his cut than KHJ. He developed a system wherein the bigger a song was, the more frequently it aired: The #1 song was on the radio every 70 minutes. The lowest-selling currents only aired every 4 hours.

So how old were the songs on “play it safe” WABC?

The “Album Cut” Problem: How Hippies caused Callout Research

1969 marked the end of an era. The music we now call “Classic Rock” was growing beyond the youth counterculture and going mainstream, usurping the pop-based Rock ‘n’ Roll “Oldies” that dominated from Elvis’ emergence to the Beatles’ breakup.

More young people were listening to Rock on FM, not Top 40 Pop on AM.

They were also buying albums, not 45s of individual songs.

That presented a problem for radio’s primary music research tool—record sales. Sure, you could find out how many copies of Led Zepplin IV sold, but were record buyers getting it to hear “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven,” or "Misty Mountain Hop?" Now that the Album Rock format on FM radio was making real bank, radio wasn’t content to simply let some long-haired disc jockeys pick the tunes.

What radio ultimately did was call up listeners at random and—if they found someone who liked their kind of music—asked them which songs they knew and liked. They called it “callout research,” because.. well… they called people. By the mid 70s, stations using callout knew that “Show Me The Way” and “Baby I Love Your Way” were the real hits on Frampton Comes Alive, even if “Do You Feel Like We Do,” was musically more intriguing.

While callout’s original raison d'etre was to find the hit tracks on albums, by the late 70s, Top 40 Pop programmers also recognized callout’s advantages.

The first major lesson radio learned: People still love hearing their favorite songs long after people have stopped buying them. Typically, sales of even the most popular songs would dry up after about three months. But when you flat out asked people which songs they loved, big hits could last many months longer.

One early Top 40 adopter in the late 70s reported that Chicago’s “If You Leave Me Now” was still his listeners’ favorite song after 13 months.

In hindsight, this finding shouldn’t have been earth-shattering. Just because new fans stop buying a record doesn’t mean the folks who already bought it stopped listening to it. Somebody is still playing their original Dark Side Of The Moon LP if they haven’t hawked it on eBay.

As callout research evolved from a secret weapon in the 70s to the industry standard in the 80s, the biggest impact was radio continuing to play big hits for months instead of weeks. A new category of song emerged—the “recurrent”—songs listeners no longer think of as “new”, but that aren’t yet “old,” either. While radio stations still emphasized and exposed brand-new releases, the emergence of “recurrents” inherently made less room for newer songs.

Four decades later, a change in audience measurement inadvertently attacked new releases.

How an outdated beeper thingy killed radio’s new music

In 2007, radio fundamentally changed how it measured its audience in America’s 50 biggest metro areas: It replaced paper diaries that ratings participants would fil out—usually imprecisely—with a system that measured minute by minute which stations they actually heard: The Portable People Meter, which still looks like a 1990s beeper in 2024, instantly demonstrated that commercials (duh) or overly chatty DJs (duh) caused listeners to tune out.

It also showed something surprising: Listeners tuned out when stations aired new and not yet familiar songs.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise. For decades, callout research showed that it took time for most listeners to warm up to new songs. However, programmers assumed listeners wanted their stations to keep them up to date with the newest songs. They wouldn’t even test new songs in their callout research until they’d played the song enough for listeners to recognize it. They developed metrics such as “potential scores” to compensate for new songs’ lower familiarity.

Seeing evidence that listeners were tuning out when new songs aired made radio throw out that assumption.

Sure, radio still played new releases, but they hid them after long commercial breaks. Disc Jockeys stopped announcing new releases, much less hyping them. Features like “Smash or Trash” designed to spotlight brand new songs vanished. Ultimately, radio waited longer to add new songs and played new songs less often when they finally did.

Radio stations hoped listeners wouldn’t notice the new songs they played. Unfortunately, they quickly got what they hoped:

Radio Becomes the Old Music Medium

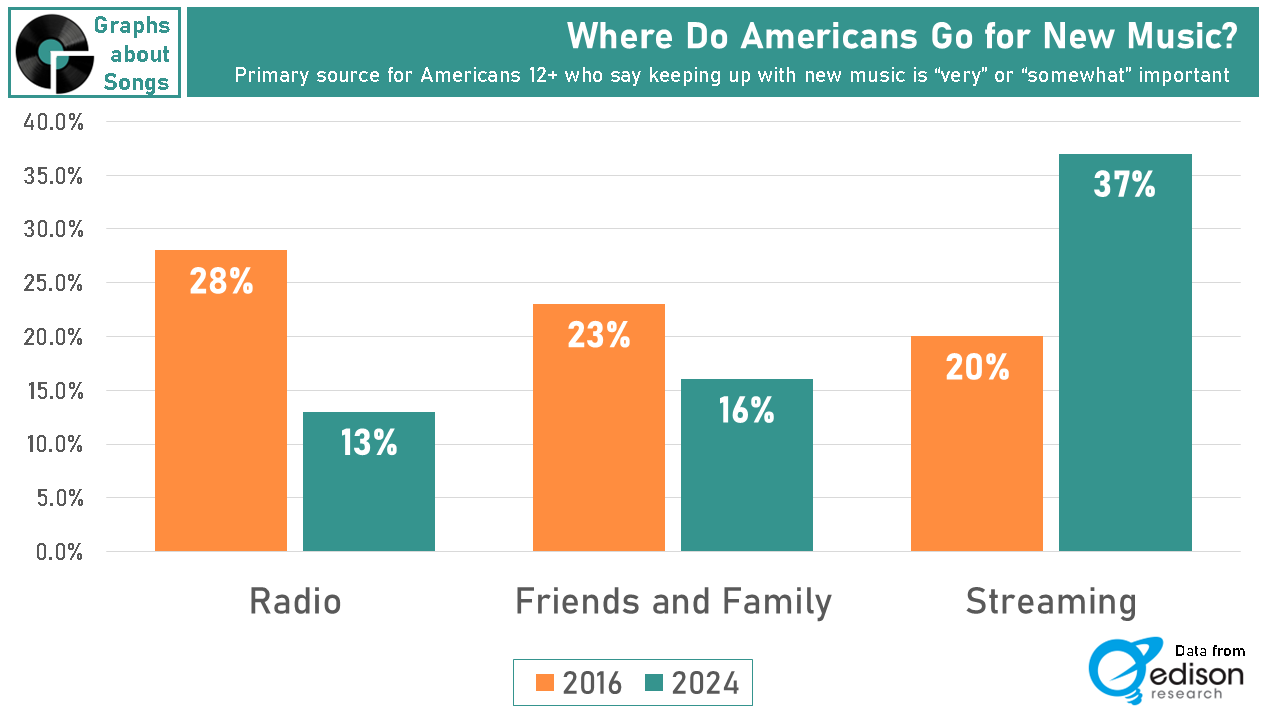

Edison Research’s 2024 Music Discovery Report found that Spotify and YouTube are now the leading ways listeners say they discover new music. No surprise there. What might surprise you is how quickly that shift occurred: Edison finds that among Americans who said keeping up to date with new music is important to them:

In 2016, 28% primarily used radio to do so—easily the #1 source. Streaming sources—including Spotify, YouTube and Apple (iTunes)—were the primary new music discovery source for only 20%, behind radio and Friends and Family (23%)

In 2024, things have flipped: 29% primarily use Spotify, YouTube and Apple Music to keep up to date with new music. Add TikTok and it’s 37%. Meanwhile, a scant 13% primarily rely on radio to keep up to date with new music.

In other words, radio had a two to one lead on streaming on keeping up with new music. Today, it’s streaming leading radio by almost two to one,

Is this really a problem?

No.. And yes.

As I explained in Does The #1 Song Even Matter Anymore, there are two types of music consumption patterns:

Artist Stans seek out new music from artists they love and binge it on Spotify as soon as its released. This consumption pattern has helped Drake and Taylor Swift to upend decades old chart records as their fans repeatedly sample every song on their latest albums. While Artist Stans represents the lion’s share of streaming plays when a song is brand new, they ultimately are a small share of people who like a song if that song becomes a mass-appeal hit.

The rest of a hit songs’ consumption comes from Causal Fans. They don’t seek out the song, but learn about it when someone else plays it for them. They don’t binge it on streaming as soon as they hear it, but instead warm up to the song over time. And even though they take longer to discover the song and don’t play it as often when they do, Casual Fans ultimately comprise the bulk of a song’s consumption over time and make the song culturally relevant.

Radio is the quintessential medium for Causal Fan consumption. Historically, it’s been the #1 way people discover new songs that they didn’t camp out at Sam Goody to buy. Radio’s time frame for playing contemporary songs reflects how Causal Fans warm up to new songs: It typically takes about eight weeks for familiarity and appeal to peak.

So if both ratings data and music research indicate that waiting until songs are at least two months old to play them to optimize your appeal among listeners who are Causal Fans, what’s the issue?

The New Music Paradox

Radio’s electronic measurement data may show when listeners tune out, but it doesn’t show why listeners tuned in to a radio station in the first place.

If you choose a “Classic (-Hits”, -Rock”, al”) station, you’re there for a curated experience of the best of the past.

However, listeners who choose a contemporary station, whether Pop, Country, Hip Hop, or Alternative, specifically want their station to keep them up to date on today’s music. In the short run, you might not be interested in hearing a song you don’t recognize and tune away. However, in my 15 years of working with one of radio’s leading research firms, I consistently saw that “hit” music stations that focused too heavily on songs listeners already knew and loved ultimately lost listeners: Over time, fewer and fewer people tuned in because the station was no longer meeting their expectations.

Sure, they were playing songs they liked, but they were playing yesterdays songs, not today’s hits. And that’s not what they promised their listeners.

Five Recommendations for Radio Programmers

Re-embrace new music: It’s been tough to find new songs—particularly in the Pop genre—that resonate these last few years. That’s changed in 2024: From Sabrina Carpenter to Chappell Roan, people are hearing new songs they like again. Focusing on older songs in 2024 can quickly make your station irrelevant.

Give listeners a reason to try new songs: Radio’s no so secret weapon are its personalities. Listeners expect those personalities to know and love the music. They also expect those personalities to introduce them to new songs they’ll love. Use your personalities to provide the context listeners need to stick around to hear new releases.

Play new songs frequently enough for them to become familiar: Being too conservative with how often you play a new song can backfire. By the time a listener hears the song again, they have no lingering memory of the last time they heard it—which means they’re not cumulatively building familiarity. You’re better off playing a new song frequently so you can find out if listeners love it or hate it quickly.

Focus on a small number of new songs you believe will be huge: That’s especially important if you’re playing those new songs frequently. The Hit Momentum Report can help you leverage streaming data to find those new songs with the great hit potential.

Consider your image: Your image is how listeners perceive you. If they perceive you as being in touch with today, they’ll tune in—even if they hear a song they don’t yet know. If, however, they perceive your station as being out of touch and stale, even if every song was a hit, they won’t ever tune in to you in the first place. Sure, most listeners are only now fans of that song that dropped three months ago, But for the listeners who binged that song on Spotify when it dropped, your claim that it’s “new” just ruined your credibility with that listener for all the other songs you play.

Remember how 93/KHJ played a small number of brand new songs as often as its most established hits? That formula gave Southern Californians the perception that KHJ was far more hip than its music actually was.

C’mon, man, radio’s dead

If you believe radio is towers in fields (and I do love me some towers in fields), then yes, it’s over. The 21st century belongs to IP based media delivery. Thanks for reading.

If, however, you believe radio is a real person curating, sharing, and commenting about music, for a community that gathers in real time to experience it, then radio’s appeal is eternal. Sure, we might not recognize its future forms or delivery platforms, but humanity’s interest in music is among our most timeless traits.

Sources for this post:

Mediabase - Published Panel - Past 7 Days: http://www.mediabase.com/mmrweb/fmqb/charts.asp?SHOWYEAR=N

Spotify Charts (2019-2024 for the USA): https://charts.spotify.com/charts/overview/us

Edison Research - The Music Discovery Report: https://www.edisonresearch.com/the-music-discovery-report-released-by-edison-research

ARSA — THE AIRHEADS RADIO SURVEY ARCHIVE: http://www.las-solanas.com/arsa

David Martin, N=1: On the arts and sciences of media, “Top 40, The Fox and The Hedgehog”: http://davemartin.blogspot.com/2004/09/it-requires-very-unusual-mind-to.html

That’s why I created HitBound Radio at www.HitBoundRadio.com. 80% of the songs are less than 2 months old.