Five Ways Streaming has Structurally Changed Pop Music

From beginning to end, the very elements that have defined Pop songs for decades are changing. Why? To maximize the royalty payments you generate.

Today’s Graphs About Songs are literally graphs of songs.

The graphs you’ll see are the actual waveform of some of the biggest hits from today and back in the day. In literally looking at songs, you’ll see five specific ways Pop songs are structurally changing.

Specifically, the five changes you’ll see reflect how yesterday’s hits were designed to entice radio to play them. Today’s hits are crafted so you and your fellow Spotify subscribers will play them.

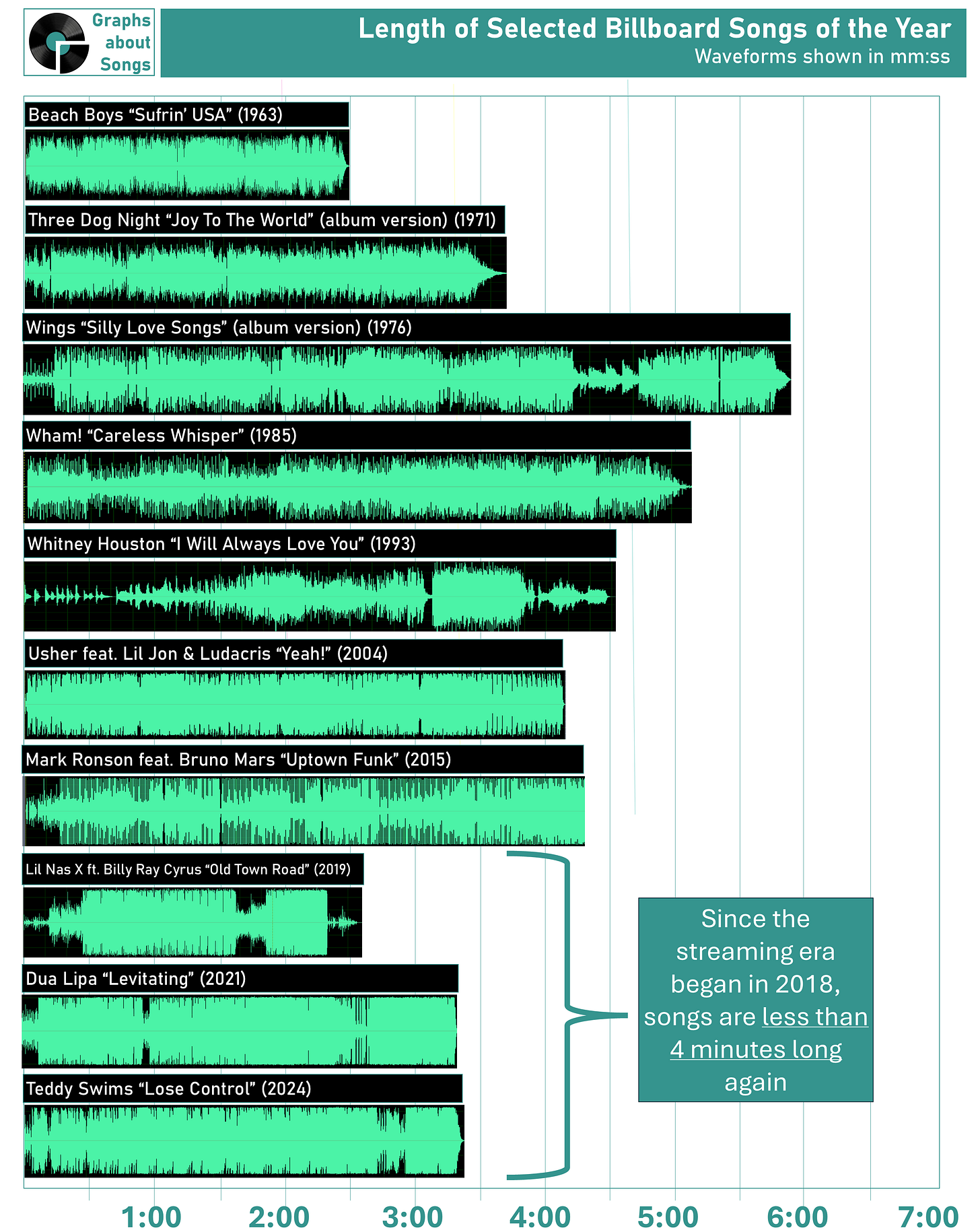

#1: Songs are Shorter (Again)

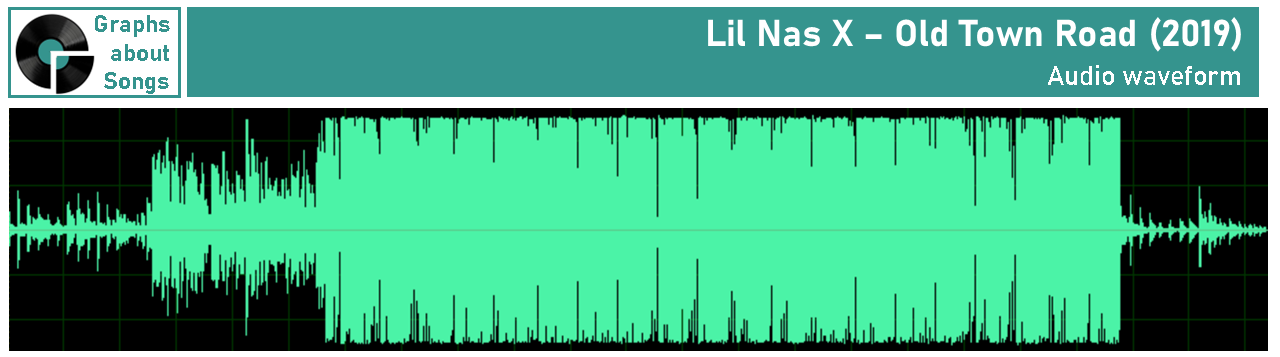

When “Old Town Road” took the record for the longest run at #1 in 2019, it did so as an usually short song. The Billy Ray Cyrus remix that became the definitive version is only 2 minutes and 37 seconds long. The original Lil Nas X version runs a mere 1 minute and 53 seconds.

While that time sounded strangely short to our ears in 2019, it’s a return to the typical length of a Pop hit for most of recorded music history.

For the first half of the 20th century, the 10” 78rpm record limited the length of a song to under four minutes.

The LP ended that limit, but Pop radio still preferred songs that were around three minutes long.

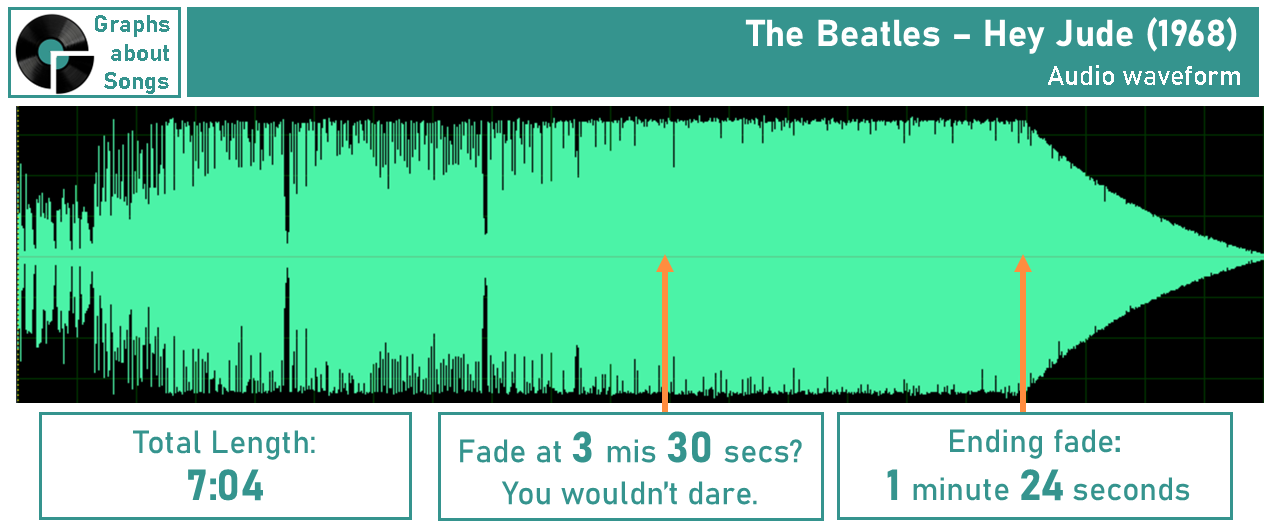

The Beatles were likely the only artist influential enough to break the four-minute cap: 1968’s “Hey Jude” is over seven minutes long---and most radio stations played it out for at well over five minutes.

Later in ‘68, Richard Harris’ “McAuthor Park” took 7 minutes and 11 seconds to leave your cake out in the rain.

1971’s American Pie from Don McLean clocked in at 8 minutes 33 seconds. (The 45 version actually required flipping over the record to hear the second half.)

Continuing through the 1970s, Rock artists would routinely record lengthy versions for albums that FM rock stations played in their entirety, while labels released single versions on 45s that AM Top 40 stations played that often were only half as long.

Here’s a selection of Billboard Songs of the Year selections: to illustrate how long a hot song could be.

These songs don’t specifically represent the average length of a hit song: 1994 was the peak for average length, with Pop hits routinely well over four minutes. While songs did begin trimming up in the 2000s, songs over four minutes remained routine even well into the 2010s.

So why are so many songs since the late 2010s clocking in at barely over 3 minutes?

Composers and performers receive royalty payments by the track, not by the minute. If a song is catchy enough to encourage you to listen again, that’s two royalty payments.

How, exactly, are they shortening those songs?

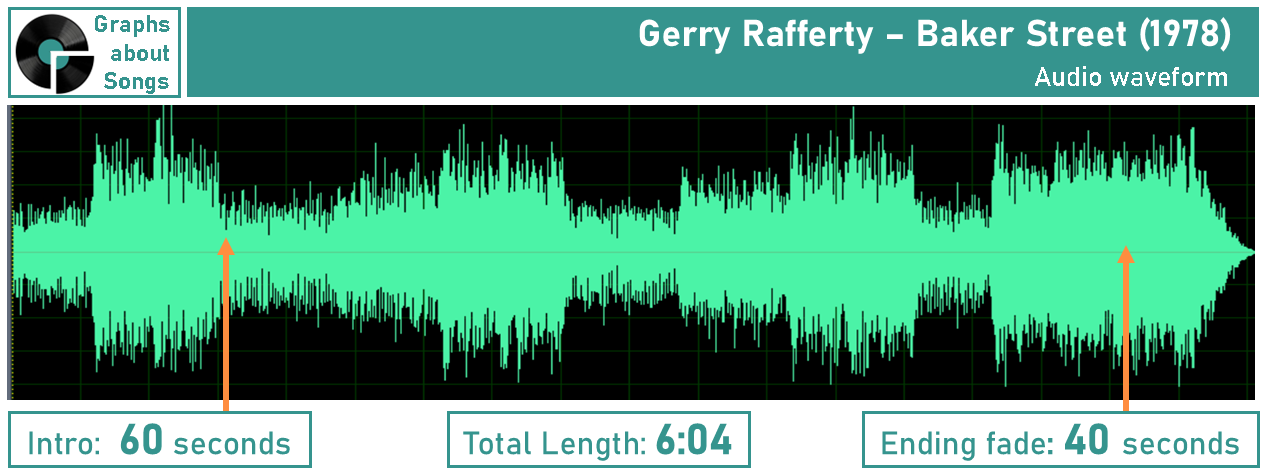

#2: Intros are Shorter… Much Shorter

The “intro” is the instrumental section at the beginning of the song before the singer starts the first verse. It’s the introduction.

At the peak of the Classic Rock era, these song intros often got really long. Consider Gerry Rafferty’s 1978 “Baker Street”. With its legendary saxophone intro (that Dave Ramsey uses for his radio show’s theme—presumably paying cash for those royalties), you’ll wait a full minute for the first verse to begin.

Heck, the intro even has its own into:

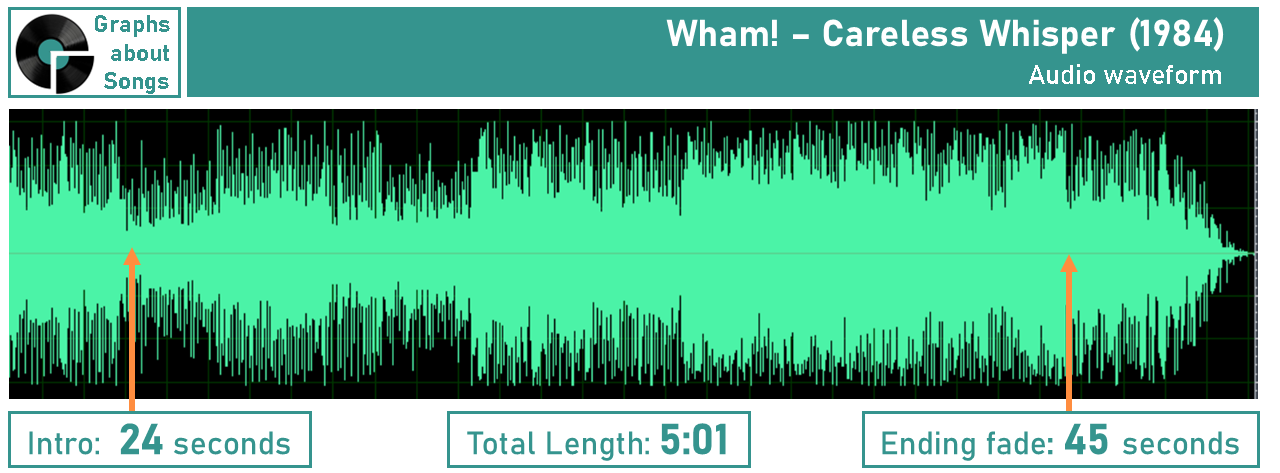

Or consider the iconic 24-second saxophone intro for “Careless Whisper”.

Radio personalities have long loved talking over the intros, telling you everything from today’s weather to your next chance to win a family four pack of Tate McRae tickets. We particularly love ending our spiel at the exact moment the singer begins—it’s called “hitting the post” and it gets radio people turnt.

It’s a craft Broadway Bill Lee at New York’s 101.1 CBS-FM has brought into the Tik Tok era:

Today’s songs only give you a few notes before the vocal.

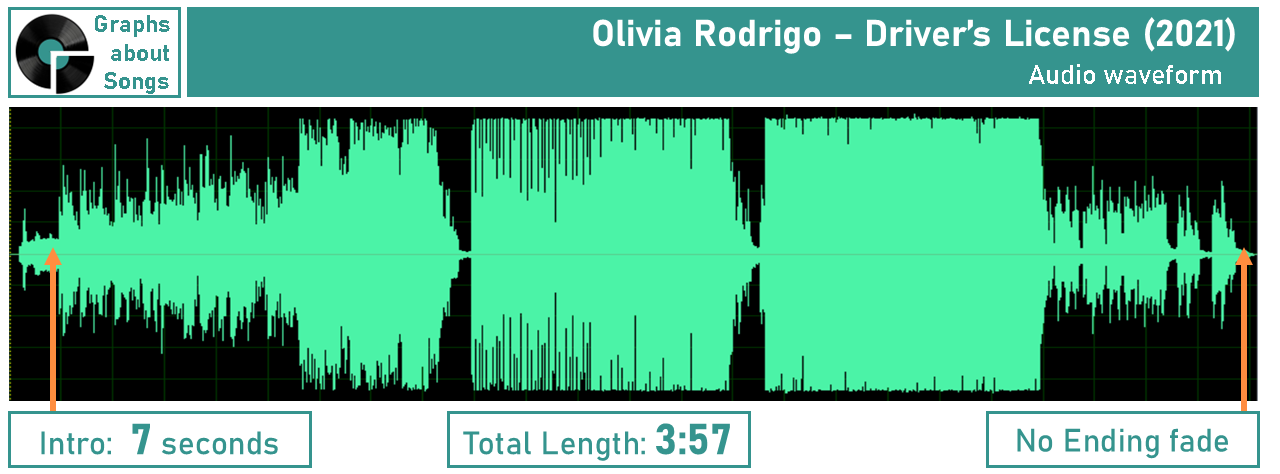

Look at Olivia Rodrigo’s “Driver’s License.” You’ll only wait seven seconds for Rodrigo to explain why one of the happiest moments of a teenager’s life was ruined by her fickle ex-boyfriend. Plus, that intro is the actual sound of her mom’s car chiming when turning the key. It’s an intro designed to capture your curiosity.

In the streaming era, a better song is always a skip away. Each song only has a few seconds to convince you to keep playing it. If you skip it before playing at least 30 seconds of the song, the performers don’t get paid for your listening.

Also notice how “Driver’s License” doesn’t fade out, but simply ends?

#3: Fade-Outs are Disappearing Entirely.

You know when a song sounds like they just turned down the volume slowly while the band kept on playing? That’s a fade out. Turning down the volume is exactly what happened when they produced it.

For decades, the fade out was the typical way Pop songs end. The “cold” ending—when a song ends with a final, definitive word or note—was the exception.

Most songs fade outs weren’t very long. Consider Daryl Hall and John Oates’ “Rich Girl”, which excuses itself in a scant eight seconds.

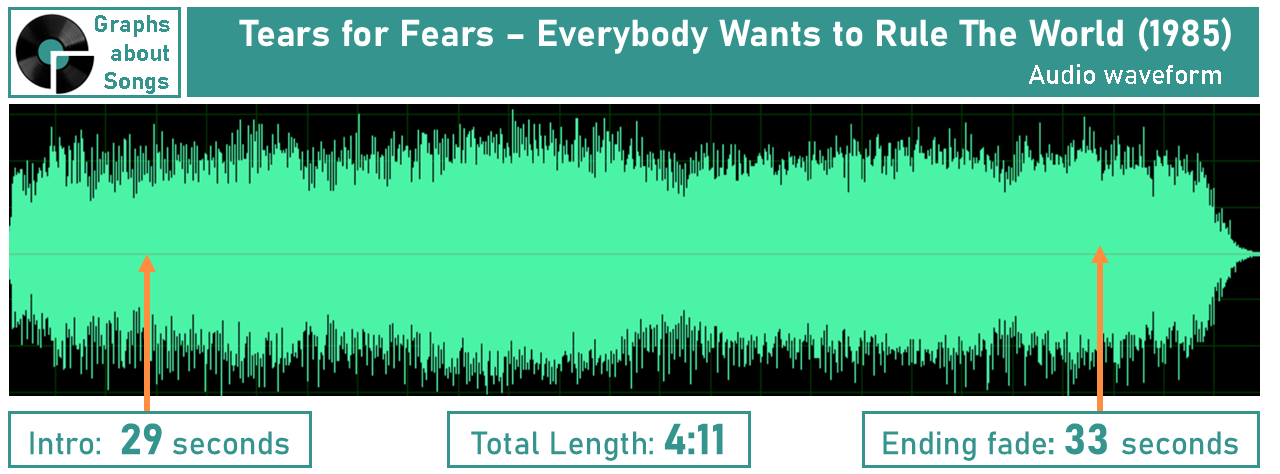

Some songs took more time heading for the exit, such as Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule The World”

While most fade outs are the simple—and arguably uncreative—way to end a song, some artists used fade outs to make their songs stand out.

The Beatles’ Hey Jude is more famous for its fade than the rest of the song.

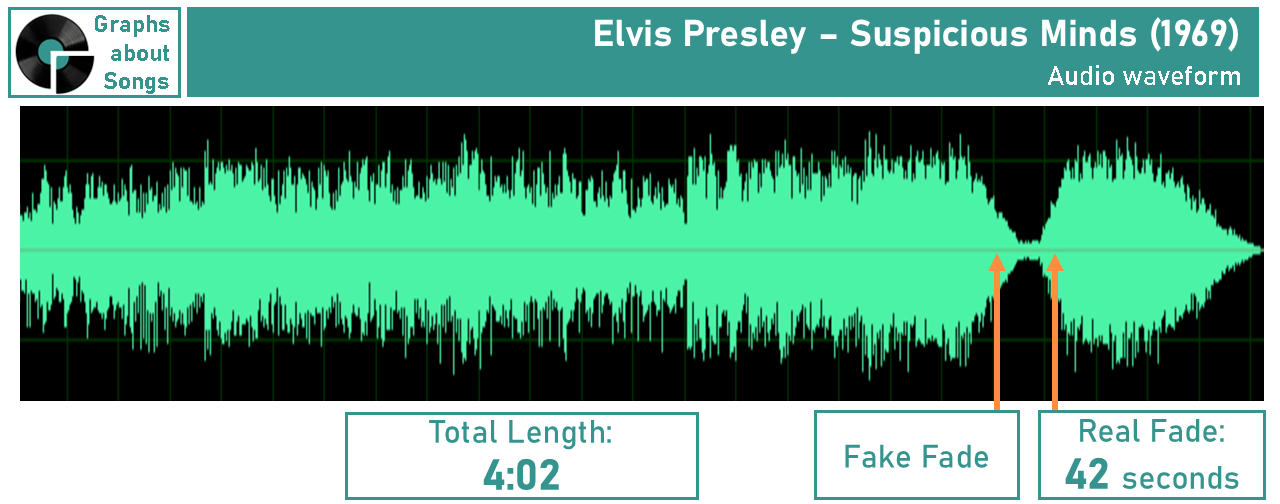

Elvis Presley’s 1969 comeback hit “Suspicious Minds” turned a fake fade into an encore performance—and a nightmare for unsuspecting radio DJs.

Then there are the artists who discovered you could slip things by the censors if you buried it in the fade. Listen to the very end of Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing for an… uh… aroused example.)

Just like song intros, fade-outs were made for radio.

The radio personality could talk over the fade out of one song and seamlessly transition into the next one while finishing the weather. Or, she could simply start the next track on the beat of the fade out.

Fade outs also made it easy for stations that aired segments at specific times, such as newscasts or sporting events. Consider Al Stewart’s biggest hit: No, it’s not “Year of the Cat,” but rather 1979’s “Time Passages.” The album version gives you over two minutes of wiggle room for fading out the song.

(If you’re one of our radio geeks, can’t you just hear the Top of the Hour legal ID after this song…)

What was a feature for radio is now a bug for streaming.

Once a streaming user realizes, “I’ve already heard this part” and the song is basically over, they skip to another song. If, however, a song reaches a definitive end, you might play the song again if you find the song’s conclusion satisfying.

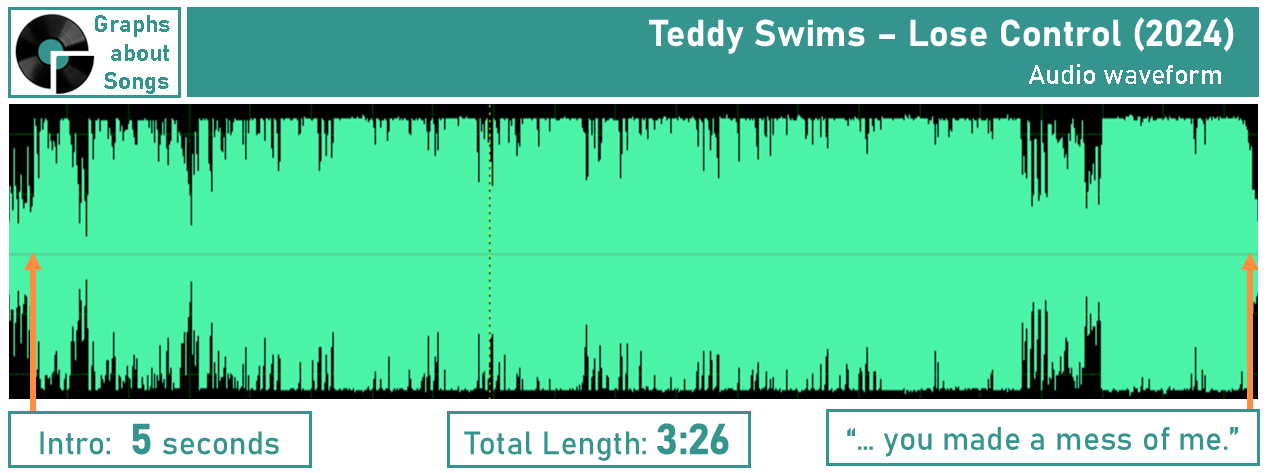

Examine last year’s Song of the Year, Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control.” Not only does it only have a 5 second intro, it ends with a rousing completion of the chorus:

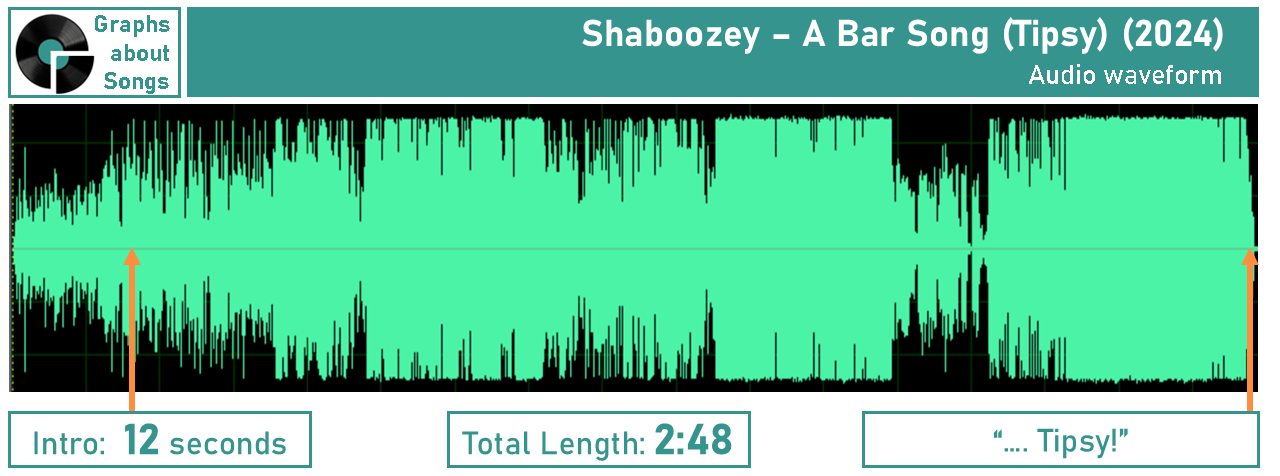

Or consider Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy). It ends with one final chant of “Tipsy!” (If you listen very closely at the end, you can hear Shaboozey getting kicked out of the bar.)

Finally, there’s Chappell Roan’s debut hit “Good Luck, Babe!” It does have a luxuriously long 15 second intro by today’s standards. Instead of yesterday’s fade out, Roan slows the song like a record player losing power to accentuate the lyrics:

Some psychologists speculate the fade out is disappearing as we grow to understand humans’ strong desire for closure. Personally, I doubt record producers are reading psychology today. It’s all about those Spotify Benjamins.

#4: “ABACAB” Structure is No Longer a Given.

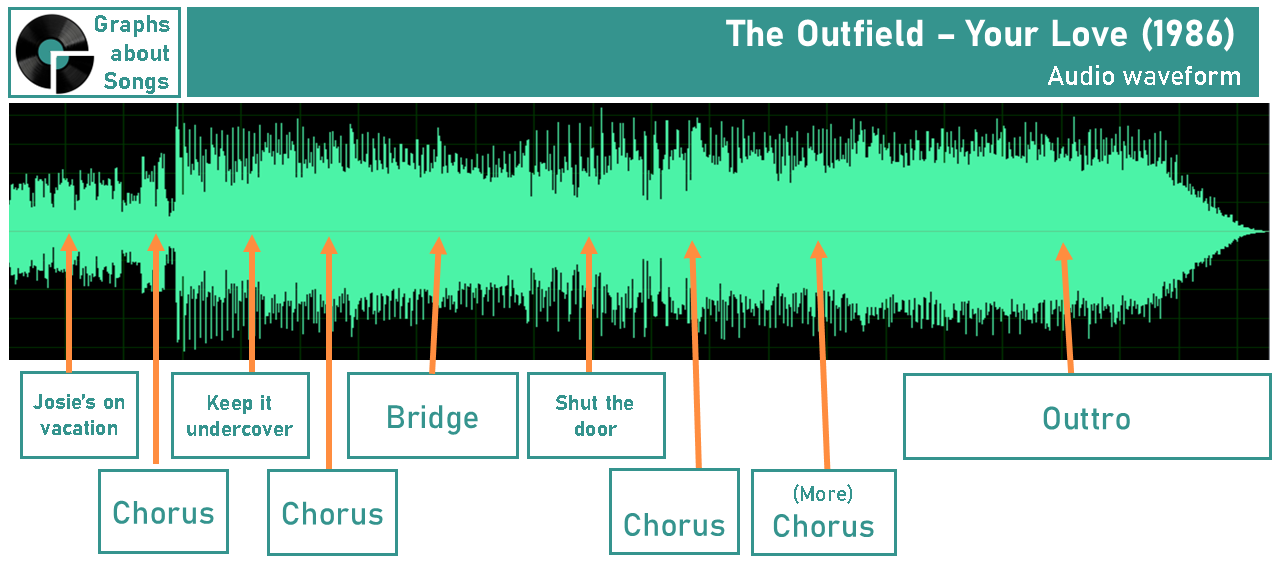

When The Outfield wanted to use (but not lose) your love tonight, they expressed in no uncertain terms their limited level of commitment using the most conventional song structure around: A-B-A-B-C-A B:

It’s the quintessential structure of a Pop song: first verse, chorus, second verse, chorus, bridge, last verse, chorus.

There are variations. Some songs omit the third verse and go back to the chorus after the bridge. (Who needs a third verse when a verse can be broken?)

Country songs typically only had two verses, which is why it was such a huge deal when Garth Brooks recorded a special version of “Friends in Low Places” with a third verse.

Rock hasn’t always stuck to this tradition. Several Rock classics became big Pop hits with unusual structures. Consider Bohemian Rhapsody. Or Crosby Stills & Nash’s “Suite Judy Blue Eyes” is famously a “suite” of song snippets:

In the realm of Pop hits, however, traditional song structure ruled.

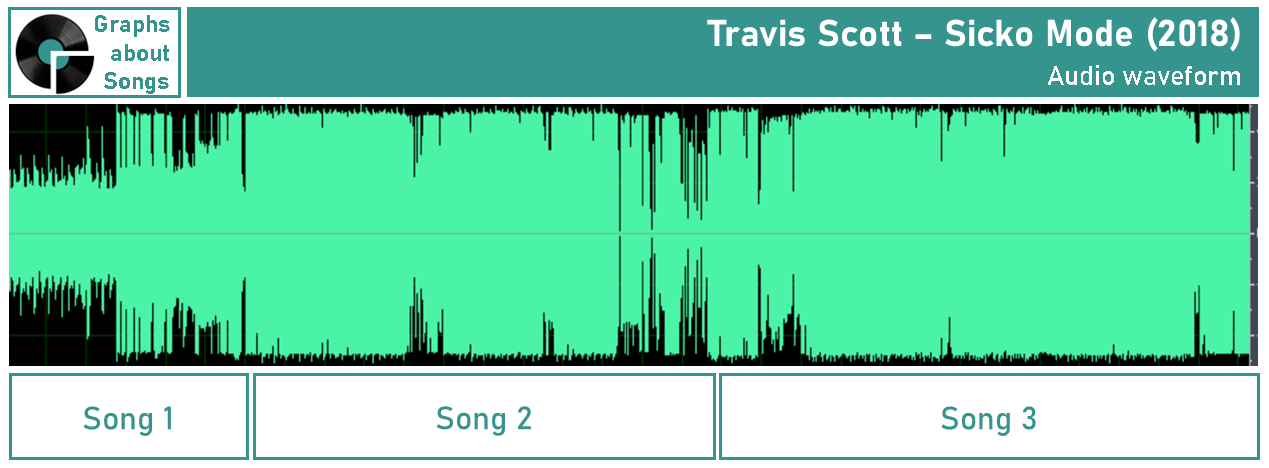

Then in 2018, Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode” took it to a new level. This #1 hit is essentially three different songs in one.

A year later, Billie Eilish’s #1 “Bad Guy” followed a relatively conventional song structure until the curve ball at the end.

There are still plenty of songs with verses and chorus today. However, it is no longer the given that it was for decades.

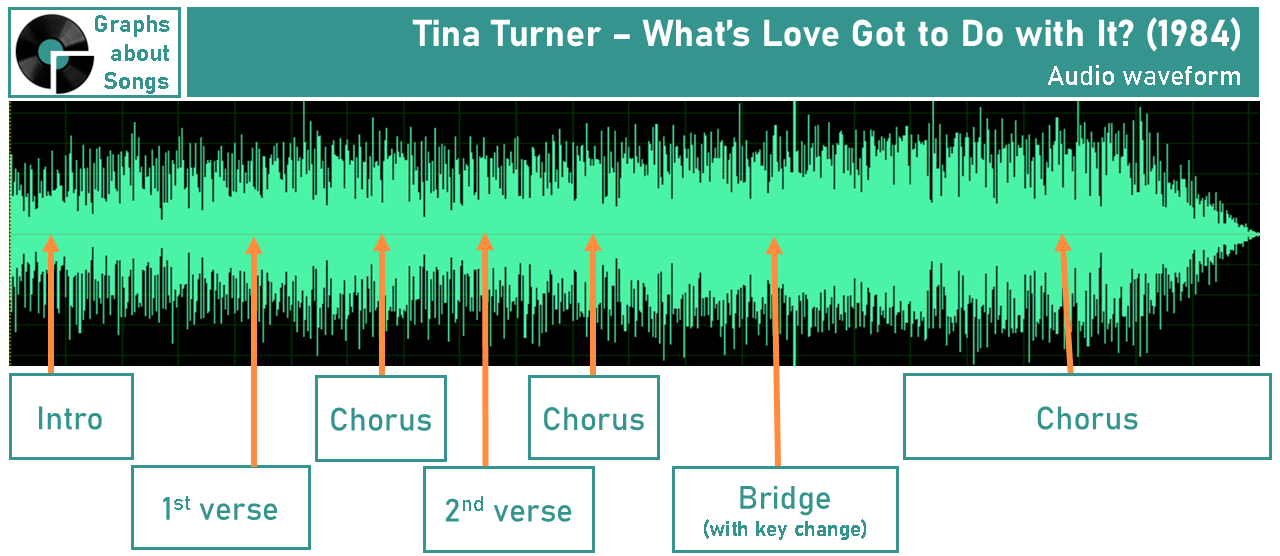

#5: Dynamic Range is Back

It’s a fancy term that simply means how much difference there is between the softer and the louder parts of a song. There are two types of dynamic range:

Long-term dynamic range is the difference between louder and softer sections of a song. Varying between softer and louder segments can make music more interesting. However, it can also be annoying if the differences are so big your listener is constantly adjusting the volume.

Bjork famously exploits this difference, even in the title of the song…

Instantaneous dynamic range is how much difference there is between soft and loud from millisecond to millisecond. The less difference there is, the louder our brains perceive the music. Plus, it helps cover up tape hiss on cassettes and noise on FM radio. Overdo it, however, and music sounds unnatural and lifeless.

The process of making a song sound louder by removing these volume difference is “compression.” (Not to be confused with digital compression, which makes file sizes smaller.) Two decades ago, making music sound loud became an outright war.

An overly simplistic explanation of The Loudness Wars

Back in the day when you spun a knob to pick a radio station, folks were more likely to stop on a station if it sounded louder than others. (There are technical reasons terrestrial radio stations compress dynamic range to maximize modulation, but this is Graphs About Songs, not This Week in Radio Tech.).

The technology to make radio sound louder evolved substantially during the 1980s.

Meanwhile, when folks popped in new CDs, they were disappointed their favorite songs didn’t sound like they did on the radio. So, the labels began using more of the same technique radio used to crunch the dynamic range from the CD. (While physical limitations in vinyl prevented this level of loudness, digital audio had no such limitation.)

Of course, when the radio station played the same CD, their own processing would compress it and make it even louder, which over time led labels to apply even more dynamic range compression. The loudness wars were on.

By the time we got to the 2000s, some songs had almost no dynamic range at all.

When music is this devoid of dynamic differences between loud and soft, it can be physically fatiguing. Some listeners even report headaches from overly-compressed audio.

Today’s teens no longer expect songs to sound like they do on Z-100 or Kiss-FM. They’re first experiencing songs on Spotify and they’re listening on earbuds or noise-cancelling headphones.

It’s the whole reason for the rise of Bedroom Pop.

Slowly but surely, producers are increasingly crafting songs to maximize this intimate experience

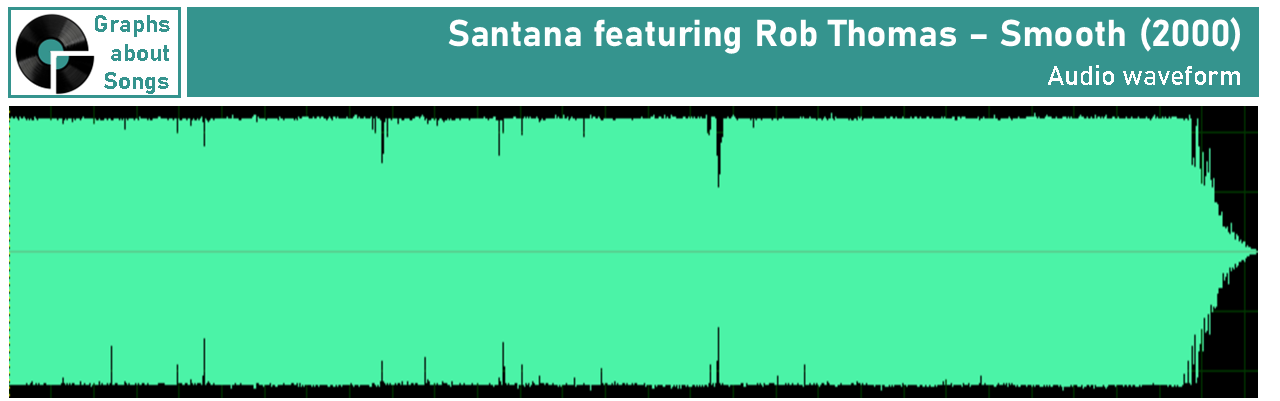

Examine how much wider from top to bottom the the waveform us for Noah Kahan’s “Stick Season” compared to Santana’s “Smooth” above. That’s because “Stick Season” has dynamic range.

Or consider how much difference there is between the soft sections at the beginning and end and the loud middle section of of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road.”

Some producers are still compressing the dynamic range out of some or all sections of a song, whether for artistic reasons or old habit. Today’s audio procession tools can obtain the technical advantages of dynamic range compression without sounding lifeless or unnatural.

The days of trying to sound like yesterday’s FM radio are over.

Songs Built for Streaming: Good or Bad?

The ultimate goal of these changes are to make songs so catchy, you want to play them again and again.

That’s the hallmark of a great Pop song.

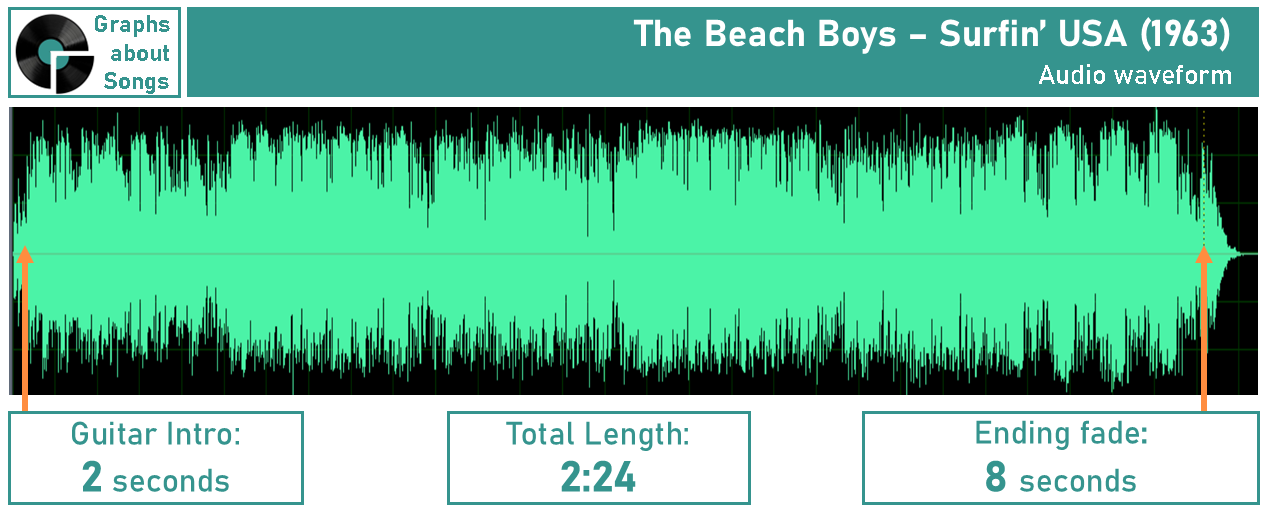

Consider The beach Boys’ iconic “Surfin’ USA.” The 2 second guitar riff reels you in. The first verse gets right to the point. The instrumental bridge bangs—but for barely six bars. When it’s over, it fades out fast.

Pure excitement. No wasted notes. The perfect Pop song.

Now consider Chappell Roan’s 2024 banger “HOT TO GO!” From the beat-counting chant to her heated cab-hailing, “HOT TO GO!” tells a story and never loses its energy in its short three minutes.

Pure excitement. No wasted notes. The perfect Pop song.

“But it ruins artistic creativity when songs are simply designed to be repeatably catchy,” I hear Classic Rock fans bemoaning.

At the risk of every Phishhead unsubscribing, some of those lengthy guitar solos of yore were more self indulgence than masterpieces.

Further reading:

Crimson and Clover helped Tommy James and The Shondells to get into the long track album era as the song was recorded at its 45rpm single length and then the song was extended for the album making it popular on both Top 40 in its single version and on some FM rock stations in its album version and there are some singles that were a bit longer than the album versions such as You Ain't Goin' Nowhere by the Byrds, Sometimes a Fantasy by Billy Joel among others.

There is also the famous deal with In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly, Alice's Restaurant Massacree by Arlo Guthrie, lots of Pink Floyd, a lot of Disco album versions, notably Love To Love You Baby by Donna Summer, etc. where some songs take a whole LP side. In the case of In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida, although Top 40 radio did play the single version, the album version is the version that actually sold the most copies. Arlo did do an Alice's Rock and Roll Restaurant single but the single stiffed but the album sold millions. The Doors, Led Zeppelin, the Peter Gabriel era Genesis (this is their most critically acclaimed period these days and their albums Selling England By The Pound, The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, etc. are often on critics' all time greatest albums lists), the 1970s Yes albums, Jethro Tull's Thick As a Brick (the whole song on both sides of the LP), etc. are known for this as well. There are promo 45s of American Pie that lasted 2 minutes or so but the editing was poor leading to AM stations playing the album version and it was first played on FM Rock stations unedited. Layla is another case when the whole album version outsold the first pressing single when FM rock stations started playing it along with Bell Bottom Blues and other tracks from the album so in 1972, Atco reissued the single commercially with the whole album version compressed to 1 side and that 45rpm single was what sold although AM Top 40 still played the original 45rpm edited version. Creedence's Suzie Q 45 was a Part 1 and Part 2 single with Part 1 being the core vocal part and the Part 2 being the instrumental ending and Progressive FM stations played the whole thing off of the album.