Contrary to Popular Belief, Contemporary Music Still Rules

Fundamental changes in how we measure music consumption make older music suddenly look more popular. Why pundits are being irresponsible with their statistics

“Nobody listens to new music anymore!”

This hyperbolic declaration isn’t merely the rant of your uncle Dave, who hasn’t liked a new song since Grand Funk Railroad broke up. It’s also the conclusion of industry experts.

In 2022, MRC Data (now Luminate) declared “old songs” comprise 70% of the music market—and new music’s 30% share was shrinking by 1.4%. Along with the growth in streaming older songs, they cited increased song sales on iTunes from bands as old as Credence Clearwater Revival. (I, too, found that CCR is among the most-played Oldies

But hold up a minute…

The ways we consume music have changed dramatically in the last two decades. Are the data that declare new music is doomed really showing what pundits claim they show? Can we even make comparisons between the days of 45s, iTunes, and Spotify?

First, we have to clarify what we’re even asking.

There are two overarching questions we can ask about the consumption of new or “contemporary” music compared to old, gold, classic, or “catalog” music.

#1: How many of the most popular songs at the moment are new songs versus old classics? If Casey Kasem were counting down the hits, how many old songs would make the show? In other words, are more and more “old” songs becoming just as popular as today’s biggest hits?

#2 Of all the music we consume, from the biggest hits to the most obscure, what is the overall balance of new versus old music? If we examine every song the typical person hears in a week, is that person playing more and more old songs compared to new songs these days? In other words, if Casey’s countdown were infinite, would there be more and more classics and fewer and fewer new hits?

Are there more Classics topping the charts?

To tackle question #1, we’ll review those Classics Spotify users play most that I’ve been reviewing in previous posts: Specifically, which songs from the 1960s through the 2010s made the weekly Spotify 200 chart in the U.S. from January 2024 through February 2025.

The graphs below show how many streams each specific genre of Classics had on a week-by-week basis. If older songs are becoming more popular at the expense of today’s releases, we will see a clear trend of older genres getting bigger with each passing week.

Let’s see if that’s happening with the four Classics genres I analyzed in previous posts.

#1: Oldies from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s

Just over one billion plays in the Spotify 200 in the U.S. went to Oldies from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, from Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” to Fleetwood Mac “Dreams” and from Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Have You Ever Seen The Rain,” to Tear for Fears’ “Everybody Wants To Rule The World.” There is no pattern of growth form week to week. Instead, Oldies’ streaming peaks in the summer, but then declines during the fall.

#2: Alternative Classics from the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s

Alternative Classics got played even more often, albeit not the era we Gen Xers would expect: From Arctic Monkeys’ “505” and Coldplay’s “Yellow",” to Linkin Park’s “Numb,” and Vance Joy’s “Riptide,” fans played these Alternative Classics from the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s 1.7 billion times. Listeners did play these Alternative Classics more often in the fall, but listening leveled off with the new year.

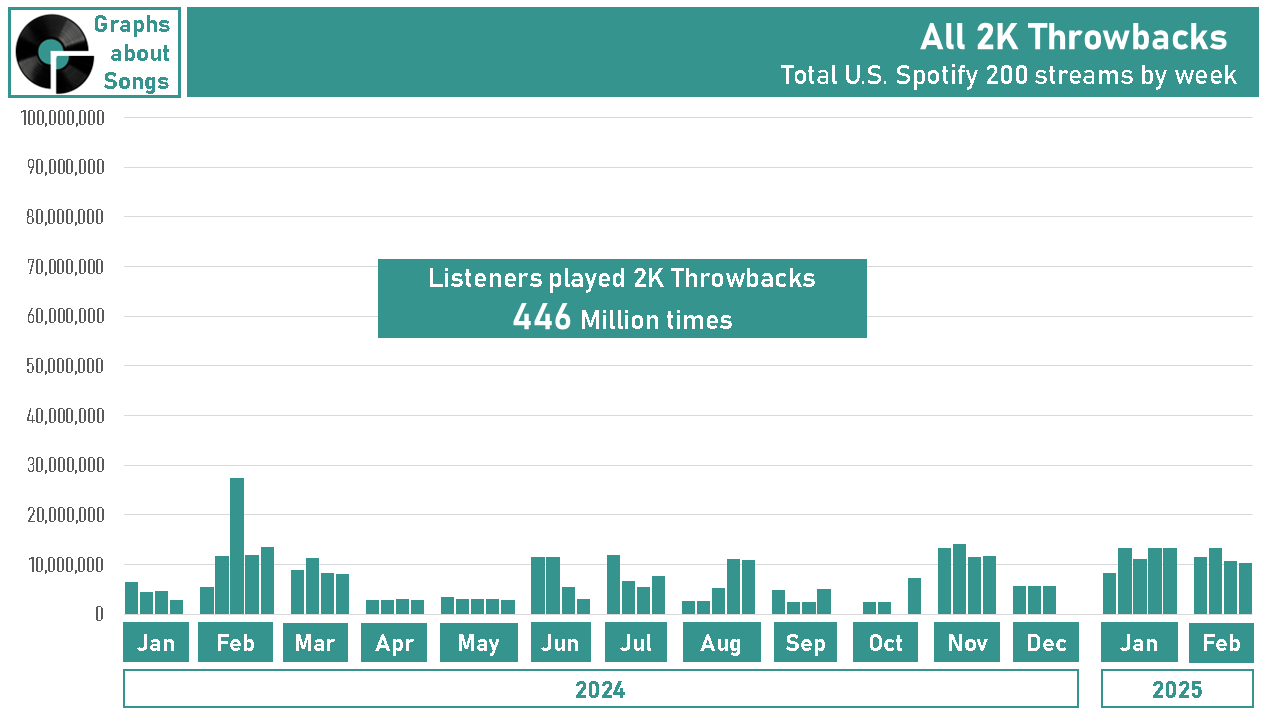

#3: 2K Throwbacks from the 2000s and 2010s

Despite hype amongst the radio industry, the 2K Throwbacks from the 2000s and 2010s that Millennials grew up hearing aren’t as popular as other classics genres. Songs like “Yeah!“ from Usher featuring Lil Jon and Ludacris, Rhianna’s “Disturbia”, and Bruno Mars’ “Locked out of Heaven,” received fewer than half a billion streams. Here again, there is no clear pattern of growth for 2K Throwbacks.

#4: Future Gen Z Classics from the 2010s

By far the biggest group of classics is both the most recent genre of old music, as well as the genre you’re least likely to hear on FM radio: The Future Gen Z Classics from the 2010s, including Tyler, The Creator & Kali Uchis’ "See You Again,” Frank Ocean’s “Pink + White,” and The Neighbourhood’s “Sweater Weather,” received over three billion plays on Spotify. Plays dipped in the spring, grew again in the fall, then dipped again during the winter. There’s no consistent pattern of these 2010s future classics becoming more popular,, either.

Holiday Music

Finally, note Holiday music, which increasingly includes Halloween themed songs in late October, but mostly is Christmas music in November and December. Holiday only covers nine weeks, but your fellow Americans collectively played Holiday classics just under two billion times last year.

How the Classics Compare to Contemporary

Those streaming numbers sound impressive until you consider that, during the same period, we played contemporary titles (in this case, songs from 2020 through today) 42 billion times.

Notice the numbers on the X axis are far bigger.

To compare the genres together, the Oldies genre in brown is almost too small to read side by side with the contemporary songs in teal.

Note that there is no clear pattern of older genres growing from month to month. During the spring of 2024, when a lot of the year’s biggest hits dropped, streaming for contemporary titles peaked, which corresponded to a slight dip in streaming for older genres making the Spotify 200.

Ignoring Halloween and Christmas music, among the songs reaching the Spotify 200, almost 87% of song plays go to contemporary songs.

Examining song streams by decade makes it even clearer: The older a song gets, the less likely it gets played on Spotify:

So the answer to question #1 is simple: If Casey were counting down the biggest songs today based on Spotify plays, the vast majority would still be contemporary songs—and there is no sign that number is shrinking.

Okay, but folks play tens of thousands of different songs on Spotify each week that rank 201 or lower—which brings us back to question #2: When we examine all the music we play, are we playing more classics and fewer new songs than we played in past decades?

We have no idea…

The Missing Data Point We’ll Never Have

As older consumers begin catching up with younger music fans in embracing streaming, they’re naturally playing those favorites with which they grew up. This demographic shift explains why streams of older titles have increased during this decade.

However, Streaming creates a far more fundamental change in how we measure contemporary vs. catalog music.

Since Thomas Edison sold his first wax cylinder until Steve Jobs gave us 99-cent iTunes downloads, we only measured consumption of the music you chose at the moment you bought it.

It’s 1994. You just bought In Utero and—no judgement—The Sign (or Happy Nation in the rest of the world) during the same Tower Records run.

Both counted equally as one album purchase.

You played “Heart Shaped Box” and “Serve The Servants” countless times until your last CD player broke in 2013. You only played “All That She Wants” five times, then gave the CD to your soon to be first ex-girlfriend around the time Tonya Harding kneecapped Nancy Kerrigan.

Since we had no way of tracking how often you actually played each CD, the record will forever show you voted equally for Nirvana and Ace of Base.

Streaming fundamentally changes that metric.

If music streaming data were analogous to music purchase data, it would only measure the very first time you play a song—but streaming instead measures every time you play a song.

The advent of streaming marks the first time in recorded music history that we know the music people actually play when they’re in control of their own music.

The change from measuring when we buy music to when we play music has fundamentally changed two things:

1) On one extreme, it amplifies the impact of fans binge listening over and over to every track on their favorite artists’ brand new release. Can you spot the week below when Taylor Swift dropped The Tortured Poets’ Department?

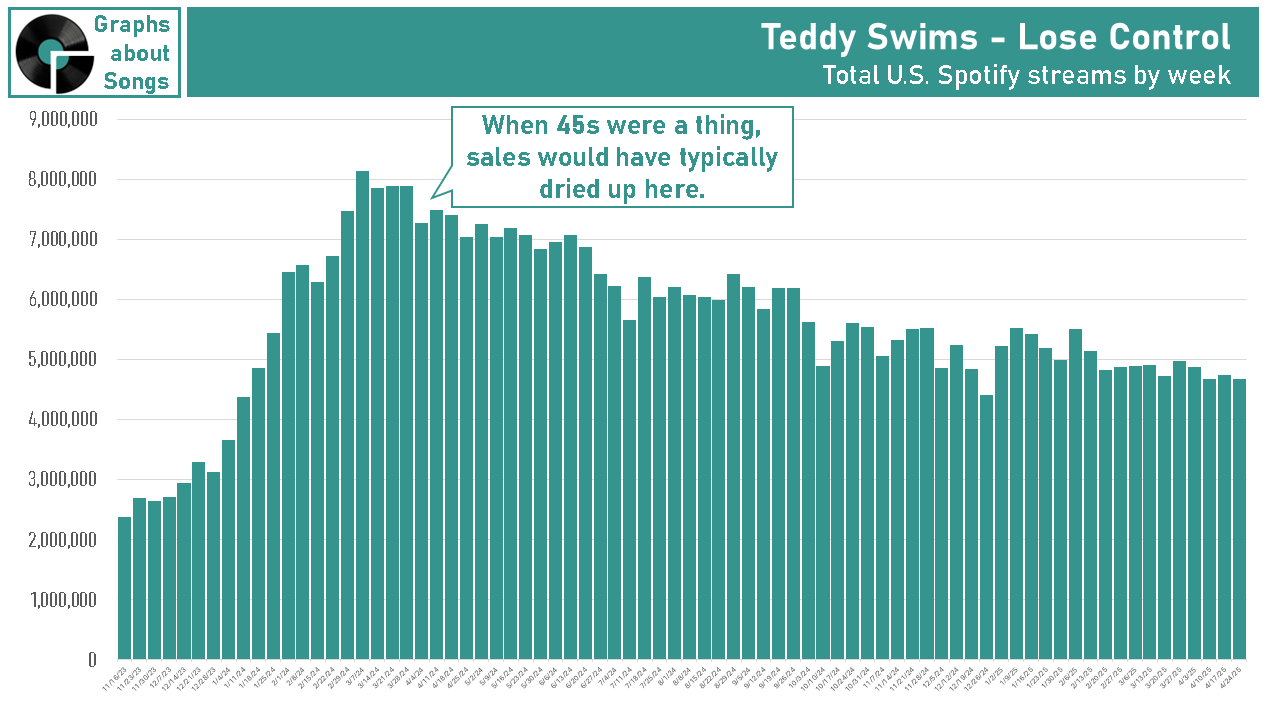

2) On the other extreme, we now capture when people keep streaming a song week after week after week. Teddy Swims’ Lose Control just surpassed The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights” with 59 weeks (and counting) in the Hot 100’s Top 10 because people still play it a lot on Spotify.

The fact is, comparing song sales to song plays is simply not measuring the same thing.

There is another way to measure the music we’re consuming—and how we measure it hasn’t changed in decades.

That medium’s role in our music consumption ecosystem, however, has also changed:

Is Radio Becoming an Old Music Medium?

Oft cited proof that people don’t like new music anymore is the decline in radio listening to Contemporary Hit Radio (CHR) stations. (That’s the Top 40 station that boasts it’s your town’s “#1 hit music station.”) During the past ten years, the percentage of radio listening that goes to hit music stations has dropped by almost 50%, now accounting for less than 5% of all radio listening.

An obvious reason is that younger people are spending a lot less time with radio, as they’ve migrated faster to streaming. In a vacuum, that demographic shift makes citing radio format ratings incomplete research.

Even among 18 to 34-year-olds still using radio, however, their share of listening to hit music stations has also fallen almost in half during the last decade.

Pundits claim its proof that even young people hate new music.

Edison Research’s Larry Rosin has a more thorough hypothesis:

Those interested in the newest music are likely scratching that itch more effectively with other, non-radio options – leaving behind bigger shares for those who want to mostly listen to older, ‘classic’ music.

As I noted in Once Upon a Time when Radio Played New Music, the U.S. radio industry’s switch to electronic passive audience measurement in 2007 inadvertently revealed that more listeners tune away when they hear a new, unfamiliar song compared to older, well-known songs. Reacting to this finding, radio stopped spotlighting the new music it played, hoping listeners simply wouldn’t notice new songs.

They got their wish: In 2016, 28% primarily used radio to keep up to date with new music. By 2024, only 13% primarily rely on radio to keep up to date with new music, while 37% primarily lean about new music from streaming or TikTok.

The State of Today’s Hits

To summarize:

Only a handful of the songs we play the most on streaming are older songs—and that number isn’t growing consistently.

Since streaming is the first technology that measures when we play a song, we cannot make direct comparisons to the days when we merely measured the moment we bought a song.

That’s not to say, though that the appeal of new music never changes.

Radio programming icon Guy Zapoleon has long noted that current hit music ebbs and flows in appeal in predictable patterns. While new music doldrums occur predictably every decade, Zapoleon has lamented that current music has been in the dumps for five years now---longer than any slump since the dawn of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

My Generational Music Theorem postulates that contemporary music is in a slump because Generation Z hasn’t yet replaced aging Millennials as the arbiters of popular music tastes. I further postulate that sometime between next week and next year, we’ll see a sudden evolution of popular music mirroring the tastes of today’s teens.

In a future post, I’ll spotlight another quirky trend of the 2020s that correlates with other fallow periods for hit music. Subscribe below to get that post in your inbox as soon as I release it. (Choose “none” for the FREE option):

Date source for this post:

Spotify Charts (weeks of 1/3/2019 through 2/28/2025 for the USA): https://charts.spotify.com/charts/overview/us

Another huge deal is when some songwriters and artists sell their publishing catalogs and end up receiving more money on their older catalog than they did when the music was current. Companies such as Primary Wave, etc. are known for buying lots of older publishing catalogs and then the writers get more money than they ever received when they were current hits and artists end up retrieving their masters when their label rights end up expiring and then sometimes sell them back to the record companies and end up receiving more money as older material than they ever received when they were current. The fact that Paul Simon owned his recorded masters for his solo catalog from the 1970s on forward is how the older CD pressings were on Warner Bros., while the LPs of the 1970s recordings were originally on Columbia. A few years ago, the Warner contract expired so he brought back his older catalog to Sony and his catalog has been administered by Sony since after he sold his royalties back to Sony.